Road Safety Implications

Four central road safety themes can be drawn from the evaluation findings as follows:

- Perceived safety is a priority for pedestrians

- Measuring walking levels and perceived safety are key road safety metrics

- Multi-year funding would enable delivery of minor measures and thus impact

- Equitable funding for walking is needed to deliver on equitable road safety

Perceived safety is a priority for pedestrians

The CSA/SRAs are fundamentally driven by a local community desire for greater road safety for pedestrians as their starting point and not by clusters of pedestrians killed or seriously injured (KSIs). This desire for pedestrian safety is captured in the CSA/SRA process in a non-technical, bottom up viewpoint of the people who actually use – and want to use – the footway as part of their everyday journeys to school, to the shops, to community destinations such as library and hospitals, and to train and bus stations. While the CSA/SRAs have an inclusive focus on children, older people and Disabled people, these population groups will make up 58% of the population by 2045, and currently represent 48% of the population. So while the CSA/SRAs represent the viewpoint of those who are most vulnerable, this vulnerability is a population norm in Scotland. This means that delivering on the CSA/SRAs will have direct relevance to increasing safe walking levels nationally.

The sum of the community identified recommendations suggest that across settlements the overall state of the footways and crossings is poor to an extent that discourages safe walking. The key road safety issues raised are slipping and tripping on the footway itself due to poor quality footways and clutter (27%), lack of safe crossings due to lack of drop kerbs & tactiles and lack of crossing facilities (24%), and then lack of footways or narrow footways which could force pedestrians into the carriageway (8%). A further 11% of recommendations were about realigning the carriageway to increase safety and comfort for pedestrians. Overall, the CSA/SRA recommendations are not driven in response to pedestrian KSIs but from a lack of perceived safety – a sense of risk and discomfort which discourages walking.

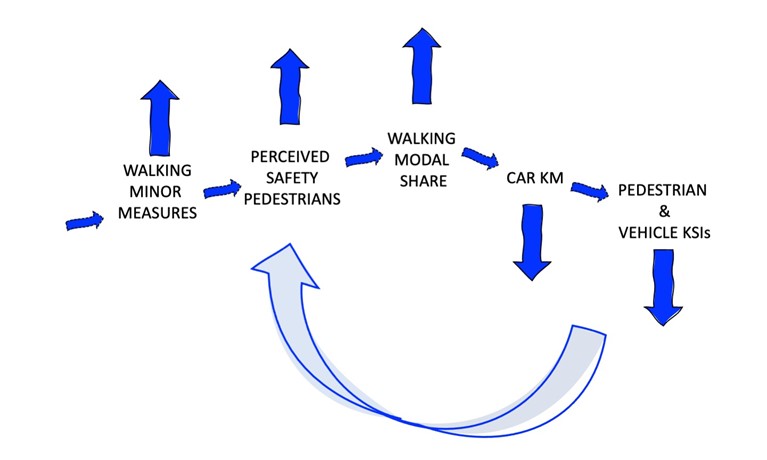

To value perceived safety is a different approach from traditional approaches to road safety which prioritise based on clusters and severity of casualties. The evaluation indicates that a walking specific approach to road safety is that the types of minor measures identified through the CSA/SRAs – if delivered - would improve the footway at critical places resulting in increases in perceived safety which together would encourage an increase in walking modal share while reducing both slips and trip and pedestrians KSIs – in a positive feedback loop. This is a prevention weighted approach which aligns with the key pillar of Safe Roads and Roadsides, one of Scotland’s Road Safety Framework 2030 (RSF 2030) five pillars. This is described as safe roads and roadsides that are:

self-explaining in that their design encourages safe and sustainable travel so that they are predictable and forgiving of errors."

Measuring walking levels and perceived safety are key road safety metrics

Because the CSA/SRAs are fundamentally driven by perceptions of road safety and not a clustering of pedestrian KSIs, investigating a causal relationship with KSI outcomes was not possible. Equally, it was identified early in the evaluation process that delivery of the walking minor measures was low, making an investigation of road safety outcomes unrelatable. The key outcome for walking in the Road Safety Framework is intermediate outcome target ‘1’: 40% reduction in pedestrians killed or seriously injured (KSIs), as a progression to eliminating all pedestrian KSIs as part of Vision Zero by 2050. This road safety ambition sits in a context of Scotland’s national policy to reduce car mileage by 20% by 2030 and the Bute House agreement which allocates £320m or 10% of the total transport budget to active travel by 2024-25. This is an unprecedented situation in road safety in Scotland where we are looking for both a substantial increase in walking modal share as well as a substantial decrease in KSIs for pedestrians.

For this reason, there is a clear case for adding more prevention and process sensitive metrics – metrics which occur before KSIs and support reducing KSIs while increasing walking. It is proposed that collecting walking data and perceived safety data are the most relevant metrics as they sit at the heart of the positive feedback loop. The flash survey conducted as part of the evaluation with community partners demonstrates that changes in perceived safety can be measured simply, albeit with the limitation that wider influences might not be isolated. The local authority interviews revealed that while walking data has historically not been collected by transport teams, this is starting to change with installation of walking and cycling counters, and camera-based surveys making this more viable. As such the following two key impact metrics are considered practicable and important:

- Collecting walking data to measure before and after levels

- Measuring before and after changes in perceived safety for pedestrians

Ideally this data should be collected by age and Disability, which may become more viable with technology. Collecting these metrics would allow assessment of the immediate impact of delivered minor measures and their contribution to Safe Roads and Roadsides. For example, if a package of community identified minor measures are delivered there may be an increase in walking levels and an improvement in perceived safety while overall area KSIs for pedestrian remain the same. While this is not a reduction in pedestrian KSIs, it would still indicate that things are heading in the right direction. This would also allow disentanglement of a safety in numbers effect at a local settlement and national level.

Collecting walking data is furthermore important to enable national reporting of pedestrian KSIs per million km, bringing Intermediate Measure 02 “Casualty rate per thousand population for pedestrians killed and seriously injured” in line with Intermediate Measure 01 “Casualty rate per 100 million vehicle kilometres for cyclists killed and seriously injured. Relating outcomes to exposure is a more robust than a per capita comparison; this is particularly important for walking where both national data and the CSA/SRAs indicate walking demand is currently suppressed. Ideally pedestrian KSIs per million km should be reported by age to differentiate and track risk in children, young people and older people who can have particularly adverse outcomes as pedestrian casualties. A final benefit of collecting walking data is that it could help prioritise road safety investment to rebalance road safety spending which is locked into the numbers and severity of accidents incurred through current high car kilometres.

Multi-year funding would enable delivery of minor measures and thus impact

Because the CSA/SRAs are strongly led from a community perspective of perceived road safety and with inclusion at their heart, they can be viewed as joined up tool for identifying critical road safety interventions with high potential impact for both accessibility and encouraging safe walking generally. This is again a strong fit with the Safe Roads and Roadsides pillar, and the overt commitment to “ensure road safety remains a key focus of active & sustainable travel in Scotland” in the of the Road Safety Framework (p. 38) on route to Vision Zero with no pedestrian (or other) KSIs by 2050. The CSA/SRAs also represent a patchwork approach to delivery which is in nature a historic conservation approach, highly viable for what could be considered the historic road environment. An obvious caveat is that the community identified measures need to be delivered for there to be an impact.

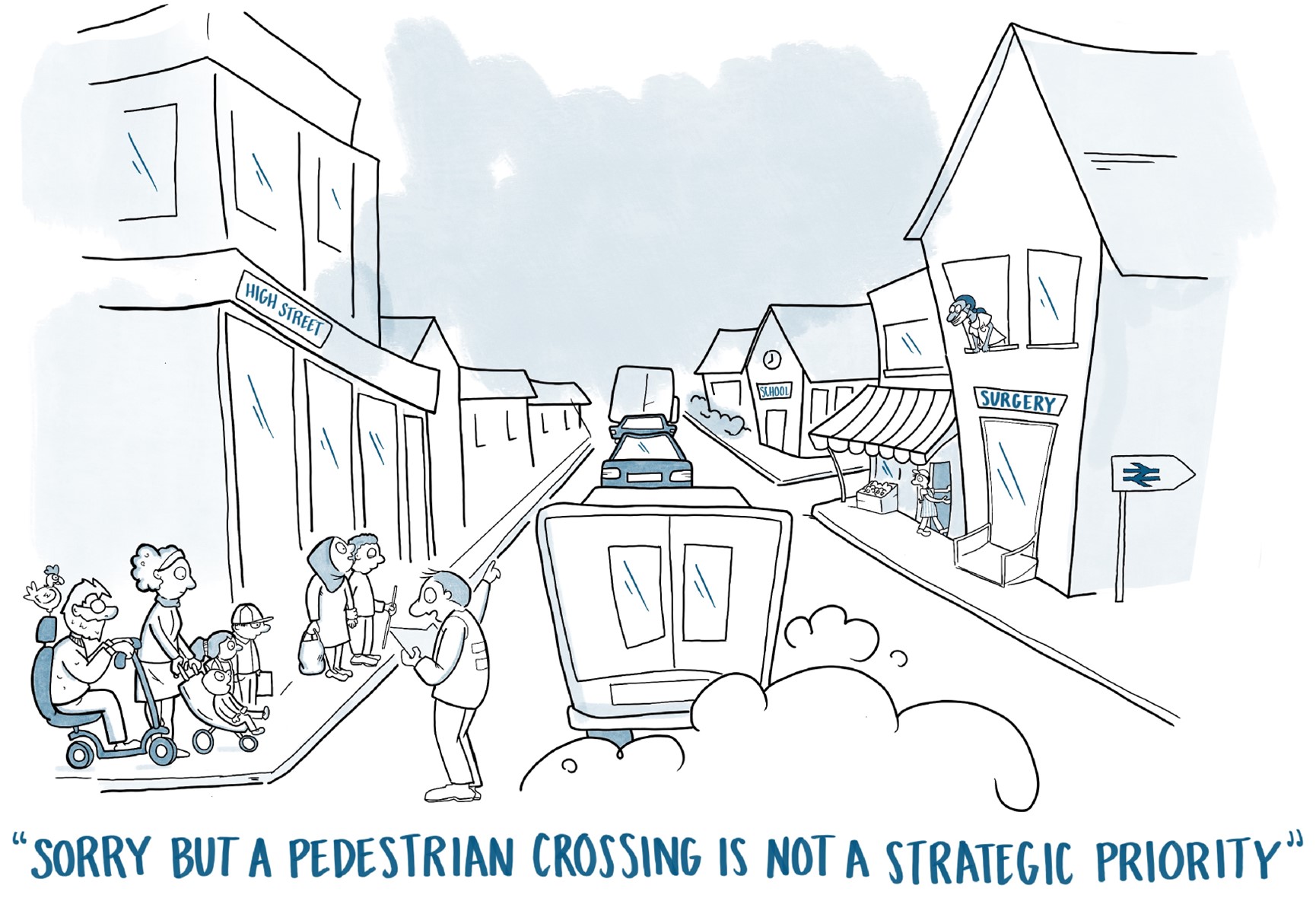

The interviews conducted as part of the evaluation highlighted that most local authority partners felt they could not fund minor walking measures through current active travel funding. Minor walking measures such as crossings or footway improvements were viewed to fall through active travel funding criteria as they are not strategic A-to-B routes. Although the CSA/SRA audits routes are indeed routes, the types of minor measures identified may lend themselves to rolling budgets where effort can be spent on coordinating delivery opportunities with other maintenance or capital works rather than on complex grant administration for such small interventions. The interventions can be delivered piecemeal, which is practical.

A multi-year partnership approach from Living Streets would assist local authorities at this time as, while the minor walking measures have a low capital investment value, they require high revenue to coordinate across service areas and funding opportunities. Living Streets can act as a bridge to community beyond the audit engagement activities to sustain community interest and manage expectations. Local authority partners also expressed a desire for greater continuity of working with Living Streets to engage with officers around understanding inclusion and on-board wider service teams. Equally, they valued the continuity of working relationships over time to support good partnership working where greater follow-up and impact tracking could support and inform delivery. A multi-year partnership with Living Streets could be envisioned as follows:

- Year 0 – Pre project, agreeing audit location, understand local priorities

- Year 1 – Conduct audit & engagement activities, collect baseline data, prioritisation

- Year 2 – Assisting in cross-service delivery coordination, delivery initial measures

- Year 3 – Follow-up, cross-service delivery coordination, delivery further measures

- Year 4 – Impact evaluation, collect after data (e.g. walking, perceived safety)

Equitable funding for walking is needed for equitable road safety outcomes

The nature of the community identified recommendations are humble and represent a small spend with large potential local impact. A high level cost estimate would be useful to understand the scale of investment more accurately. Delivering the CSA/SRAs identified minor measures is a highly achievable way for local authorities to create impact in the medium term (2023/24-2024/25) through the Bute House active travel allocations. (Of note is that safer and more inviting footways would also benefit people accessing public transport). However, this may require more dedicated allocation such as a ‘Walking Minor Measures Fund’ and multi-year funding. Fundamentally, as described in the positive feedback loop above and illustrated as a concept model in Figure 6 below, investing in minor walking measures should be viewed and valued as a keystone for road safety.

Particularly in the era of a cost of living crisis, walking is the most equitable form of transport in Scotland and deserves an equitable share of both active travel and road safety funding. Arguably, investing in walking road safety is the most direct route to achieving intermediate outcome target ‘7’, a commitment to achieving equality in casualty rates with a target of reducing the overall casualty rate for the most deprived 10% SIMD areas to the same level as the least deprived 10% SIMD areas. People who live in the most deprived 10% SIMD are likely to benefit from road safety improvements to the footway both in their immediate home and school areas but also in local amenity areas such as identified in the CSA/SRAs. People who live in the most deprived 10% SIMD might benefit most from increases in walking modal share and the associated local reduction in car km and vehicle KSIs.

Key to ensuring this positive feedback loop is that pedestrian safety is improved – both in perceived safety and in KSIs. Measures need to be delivered for there to be an outcome. The CSA/SRA audit process provides a useful joined up tool to identify critical road safety interventions with high potential impact for both accessibility and encouraging safe walking generally.

Proposed impact model - investment in minor walking measures improvements can contribute to a positive feedback loop by increasing perceived safety for pedestrians to increase walking modal shift, thereby reducing the number of km driven and pedestrian and vehicle KSIs which in turn increase perceived safety for pedestrians.