Annex A : Economic rationale for Government support of public transport and Inclusive Growth

At its most basic level, Transport has a direct economic impact in terms of jobs within the sector and the associated output but has a wider function in terms of being an enabler of other (arguably all) economic activity. Whilst some (recreational travel) may be for the simple pleasure of the activity itself, the vast majority of transport journeys are for some other purpose - delivery of freight, commuting to employment, literally accessing other markets or locations. Demand for transport, including public transport, is a derived demand and so has links throughout the economy and is a key determinant of economic activity.

Transport demand from individuals is derived from demand for other sectors of the economy (access to jobs, physical access to markets, access to services including leisure) and sits alongside demand from business to move people and goods (Another critical factor in determining demand is the level of taxation or subsidy clearly as this will affect individual transport choices).

Supply is affected by physical infrastructure but also firms’ costs for utilising that infrastructure (vehicle acquisition and running costs, staff costs, etc.) which will be dependent on any government subsidy provided in the case of public transport. The interaction of this supply and demand results in an equilibrium level of transport provision. It is important to remember that this equilibrium is the result of significant feedback effects and iteration.

Basic economic analysis talks of the factors of production in an economy being land, labour and capital, being bound together by the entrepreneur. These three high-level ways of viewing the economy are linked directly but transport has a crucial role in how those linkages operate physically and how they operate economically.

The transport sector obviously contributes to GVA directly but the key point is that, additionally, transport improvements (through building infrastructure or through policy action) will have an impact on the economy as a whole, primarily through increases in the productivity of the rest of the economy.

The transport sector, i.e. logistics, haulage and rail, air, and ferry services, run by combinations of private firms and other institutions, contributes directly to GDP and employment. Like any other sector of the economy, changes in employment and output within the transport sector will have impacts on the rest of the economy, both directly and indirectly.

More widely, transport provision, i.e. the ability to move from A to B, obviously has important economic benefits. It would seem uncontroversial to suggest that transport infrastructure is a pre-requisite for industrial development. The industrial revolution in Britain coincided with the massive expansion of the canal system in the 18th century and economic growth was greatly boosted in the period of the introduction of railways from the 1820’s onwards. There is an issue of causality here – did the improved transport infrastructure drive the industrial revolution or did the industrial revolution drive transport infrastructure improvements?

It can be argued that is likely to be almost impossible to reliably measure the impact, on the economy, of the transport infrastructure as a whole in an industrial or post-industrial economy as put simply, without transport infrastructure there would be no viable economy to analyse.

Excerpt from An Examination of the linkages between improvements in transport provision and the economy. Transport Scotland 2006

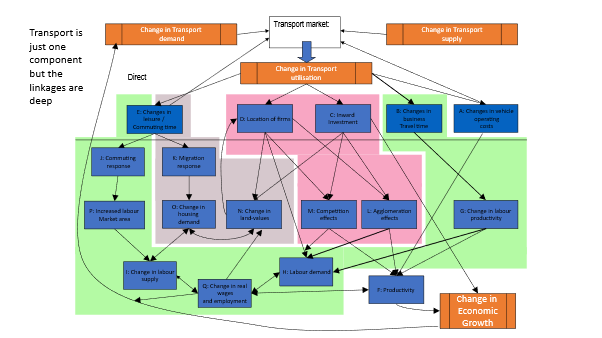

Simplistically, the transport market will have an impact on the labour market through commuting and migration effects on the supply of labour, on the capital market, in terms of the location and productivity of firms, and on the land market, in terms of the impact on land prices of increased transport provision. These impacts are complex and interlinked and affect both the supply and demand within each market. As an example, increased transport provision may cause a relocation of firms which will affect the demand for labour, whilst the increased provision may well affect the supply of labour in that area. Both of these impacts are likely to influence the land market through a change in commercial rents and/or house prices. And public transport will play a crucial part in this.

The next step is to follow through transport’s impacts on factor markets to its impact on economic growth. A change in the level of transport utilisation will have five main physical impacts. These physical impacts feed through to potential impacts on economic growth

The 5 main ways, illustrated in Figure A1, in which a change in transport utilisation has a physical impact are:

- savings in vehicle operating costs;

- savings in business travel time;

- savings in leisure/commuting time;

- the location of existing firms;

- inward investment.

Of these factors, the direct impact savings in vehicle operating costs and changes in business/leisure/commuting time currently form the foundation of Transport Economic Efficiency analysis within Scottish Transport Appraisal Guidance.

Any change that impacts on productivity will influence economic growth:

- If a change in transport utilisation causes increased inward investment then there may be a direct boost to economic growth as the productive capacity of the economy will be increased.

- Reducing vehicle operating costs reduces the price of transport. Existing journeys will cost less and whilst there may be increased demand for journeys, all journeys will have a lower unit cost.

- Savings in business travel time will have an impact on labour productivity and hence labour demand by firms and overall productivity.

- Savings in leisure and commuting time will have an impact on the supply of labour through both a commuting and migration response. The commuting response will increase the relative size of labour markets whilst the migration response will change housing demand and impact on land prices more generally.

- The (re)location of firms and potential inward investment may increase economic performance directly or through agglomeration effects - increases in productivity due to the spatial (time rather than distance) concentration of firms – or competition effects but will have an impact both directly and indirectly on labour demand and an indirect impact on labour supply through changes in land-values and hence house prices.

- Changes in labour supply and demand will result in changes in real wages and hence employment which affects productivity and economic growth.

The impact on the capital market is clearly important within this process but the effect on the labour market is central to the impact of transport on the economy as transport affects both labour supply through commuting and migration responses via the land-housing market, and labour demand through impacts on product markets.

Public transport plays a crucial role in this. The land-housing market is in turn affected by both the labour market and product markets from the location of individuals and firms. There is strong evidence that public transport availability has a particularly strong impact on land, and thus house, prices particularly within urban areas. Public transport is a direct factor in inward investment decisions, but crucially impacts everywhere due to the linkages between factors.