Framework monitoring and evaluation

This section highlights some of the key data collection, and monitoring work undertaken since 2016 as part of the ATF’s work and based on the aims and ethos set forth in the ATF and also informed by the recent lived experience testimonies of disabled people in Scotland.

This section reflects on positive monitoring work which should be supported and continued in the remaining years of the ATF, and also some areas for further development within this area, where monitoring has not been so successfully implemented.

The ATF has both qualitative and quantitative indicators in place, as evidenced in Part six and seven of the framework.

The monitoring strategies put in place for the framework were based on existing survey data gathered annually, such as:

- Scottish Household Survey.

- Bus Passenger Survey.

- Rail Passenger Survey.

- Scottish Transport Statistics.

- Scottish Crime and Justice Survey.

The positives were that:

- a variety of existing annual surveys are in place, which evidences a pre-established baseline for the data.

- the surveys have captured a wide variety of different disabled people and their experiences of travel.

- the surveys captured data on usage and experience-focused questions as well.

This report also finds that there is a suggestion to use quantitative and qualitative indicators and implementing these survey monitors is a clear and effective method of assessing relevant progress as they relate to the work streams.

Some of the identified draw backs from these surveys are:

- inconsistencies in how often key questions are asked.

- in what regions these questions are asked.

- as well as with the recording of certain experience-based questions listed in the ATF outcome indicators section annually.

Going Further: Scotland’s Accessible Travel Framework pp – 58

Accessible Travel Engagement Events Report (2016)

This 2016 Accessible Travel Engagement Events report lists the following as additional progress monitoring:

Accessible Travel Plan National Survey: Which was described as an annual survey in which disabled people in Scotland will feel included in, and informed of, the national picture of accessible transport through survey participation and feedback.

The National Survey Accessible Information Disabled Passenger draft report from 2018 shows a decrease in the response rate of 200 participants in 2016 to 61 in 2018, indicating that the continuation of the survey was deemed to be unfeasible leading to the survey being discontinued.

Accessible Travel Engagement Report June 2016 (pdf) (accessibletravel.scot)

This had a detrimental impact on stakeholders’ ability to gather substantial annual qualitative data on the lived experiences of travel from the perspective of disabled people, specifically in relation to key delivered priorities.

Longitudinal study

This has been described as the process of engagement via tracking a group of volunteers through the lifespan of the ATF, to provide further insight into potential impacts and changes working towards the improvements of accessible travel in Scotland.

Notionally overseen by Transport Scotland/the Accessible Travel Steering Group, there was to be regular discussion and engagement events held throughout the country of the type held before publication of the ATF, supplemented by online surveys which would also inform the Steering Group’s work.

Archival data reflects that the original intention was that the longitudinal study would continue over the lifespan of the ATF, to facilitate and sustain an on-going consultation between Transport Scotland and disabled people.

The Accessible Travel Engagement Event 2016 report states that DES was initially funded to initiate this study. As part of this DES set up the Longitudinal Progress Evaluation Group (LPEG) and sought input and engagement from Access Panels across Scotland.

This report finds that an aspect of this monitoring action was indeed carried forward in the form of a series of Accessible Travel Regional Action Forum Events, up until February 2020.

The aim of the LPEG group was to feedback as much information as possible about what is happening in local areas in relation to accessible travel, and in turn to gather information locally from disabled people and feed this back to Transport Scotland. The events show a clear individual and regional perspective on what their priorities were at the time, and solutions proposed. However, these events were not continued due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Collecting, collating, and promoting best practice examples is a vital action which needs to be carried forward within the on-going monitoring and evaluation work. This is a key action which goes across multiple areas of the framework’s priorities, but it is most closely aligned to Area 2 of the framework (Area 2: Developing national guidance and good practice for accessible travel issues.).

National Baseline Survey (2017) and National Survey Accessible Information Disabled Passenger Results Report (2018)

The National Baseline Survey (2017) can be used to map comparative changes in the landscape of accessible travel in Scotland. This review engages with this (2017) baseline data, alongside the second round of this data collected in a similar survey run by DES (2018).

This review looks at these as foundation project documents, alongside the recently published Disability and Transport Scottish Household Survey (2021).

The National Baseline Survey data (2017) with disabled users of public transport, could be seen as the beginning of the ATF evaluation work packages. In total, 200 disabled people responded to the survey.

Below is an overview of some of the most relevant findings from the National Baseline Survey (2017).

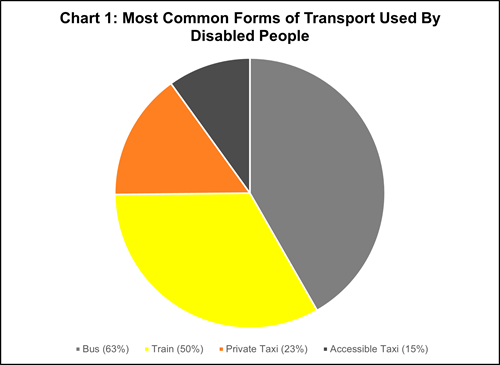

Chart 1 (over the age) reflects the most common form of transport used by disabled passengers. It shows the following use:

- Bus - 63%

- Train - 50%

- Private Taxi - 23%

- Accessible Taxi - 15%.

National Baseline Survey Results - Disabled People.pdf

*Source: The National Baseline Survey with disabled users of public transport (2017).

The data is similar to the user statistics for disabled people travelling in Scotland in 2021.

The data similarly reflects that a relatively high percentage of disabled people travel by car (similar to the 2021 survey data), with car being the most used mode of transport when combining passenger and driver.

The 2021 household survey data also shows that the second most popular mode was walking/wheeling. However, the 2017 Baseline Survey does not include walking in their list of transport modes, so we cannot accurately compare data.

Over a quarter of respondents (28%, 52 respondents) stated that they did not use private taxis as a regular mode of transport. Most also stated private hire vehicles were not wheelchair accessible, therefore preventing their use.

This is further reflected in the Disability and Transport Survey where taxi was under 10% of use across all areas of the household survey, indicating that disabled people still find taxis to be inaccessible in many instances.

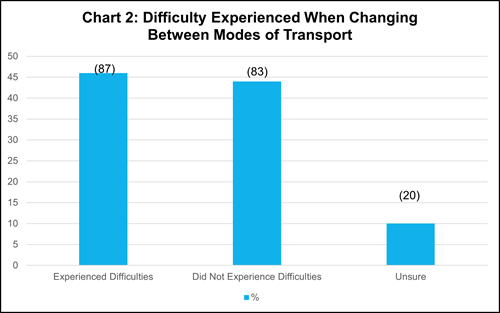

The survey asked respondents to detail whether they had experienced any difficulties when changing between modes of transport (i.e., such as when changing platform at a train station or changing between bus and train). It shows that 87% experienced difficulties, 83% did not experience difficulties and 20% were unsure.

*Source: The Disability and Transport Survey National (190 respondents)

We can see from supporting testimonial evidence that changing between modes of transport is still an area which poses significant difficulty for many disabled people.

This was also raised in a dedicated online event and a specific poll for disabled people on the topic. This showed that ease of changing between modes was still seen as a key issue.

The most common reason given by those explaining their difficulties (93 respondents) was the distance between platforms, or bus terminals which often meant that they missed a connecting service because they could not physically get between the platforms quickly enough.

Other issues raised within the 2017 baseline survey were passenger assistance, and in particular issues with appropriate and effective passenger assistance being offered.

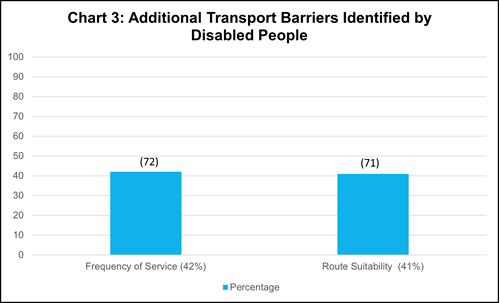

The survey collected information on the kinds of barriers that disabled people may face when using public transport. The most commonly cited was the accessibility of the mode of transport (49%, 84 respondents).

This has changed slightly, as we see in recent DES member surveys and through the data gathered in the Disability and Transport Survey, with safety and ease of access to transport changes and linkages as the main area of dissatisfaction.

This potentially indicates an increase in the accessibility of transport and resources that have taken place over the last four years. However, by gathering regular data sets this would provide clearer incremental evidence of this progress.

The chart below highlights additional transport barriers identified by disabled people. It shows that 42% identified frequency of service as a barrier, whilst 415 identified route suitability.

*Source: The National Baseline Survey with disabled users of public transport (2017).

This is similarly reflected in the inconsistencies and discrepancies with timetables and access to transport services that many disabled people experienced.

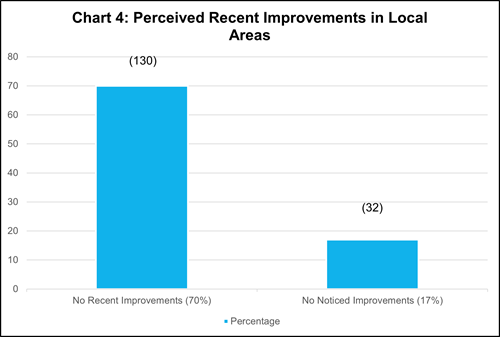

The baseline survey also asked respondents whether or not there had been recent improvements in their local areas. It shows that 70% of respondents identified no recent improvements, whilst 17% responded that there had been no noticed improvements.

*Source: Accessible Information Disabled Passenger Results Report (2018)

The improvements noted by respondents included:

- improved attitude and behaviour of staff.

- introducing audio announcements on bus routes and.

- allowing scooters access to trams.

We can see that throughout the annual delivery plans published in 2019 and 2021, and through other internal reporting channels such as the Accessible Travel Steering Group documents, that these reporting channels all evidence progress, changes implemented and work across multiple areas of accessible travel.

However, through testimonial data gathered, (via polls and direct feedback as part of consultation activities), this reflects that most respondents have not experienced meaningful or large-scale improvements to their travel experiences.

The summary of the baseline survey comments that from various accounts, transport providers had not made, nor intended to make, any large-scale changes at this time This indicates two parallel issues taking place.

National Baseline Survey Results - Disabled People.pdf

Firstly, that many of the changes being worked towards are not being consistently upheld and delivered by staff, or operators on the ground. A key issue raised during a dedicated online event, was that the barriers often begin at the point of embarking and during the journey itself. This happens more frequently than at the planning or booking stage.

Appendix 2 ATF Webinar Report - DES Summary Report Mar23.pdf

Therefore, steps need to be put in place to support consistent and quality of delivery of the priorities which Transport Scotland and other key stakeholders have worked towards since the inception of the framework.

Secondly, it indicates that there are potential issues and gaps with how information is being gathered and the forms for feedback and consultation. These are recurring issues which can be seen throughout previous and existing evaluation measures in place.

The gap in reporting or evidence of a continuation of the original survey makes it difficult to accurately track the progress and impacts that the work streams have had on the travel experiences of disabled people in Scotland. Therefore, it is difficult to track progress from the perspective of the disabled consumer, as the data gathered is primarily data gathered from Transport Scotland and other delivering stakeholders.

The data collected, similarly showed that focus groups, and facilitated regular group discussions focussed on a particular topic were the most valued method for many of the respondents.

The Baseline 2017 survey also collected examples of best practice. The emphasis from this section of the 2017 data suggested that transport providers need to be encouraged and facilitated to meet with disabled people. More specifically that space and time for genuine practice of listening and engagement need to be implemented, whether this is supported by training, or by establishing regular points of contact directly with those experiencing these issues. Similar suggestions were raised in a recent data collection exercise via a DES poll.

This potentially shows that consultation and facilitation of communication and engagement has not been made a priority within the lifespan of the ATF’s work packages to date.

Another area of data captured was responses to the question: “What changes to information would make the greatest difference to your ability to travel on public transport?” In response, many respondents articulated that accessible, clear, and up-to-date timetables would be crucial for progress in this area.

This was raised as a critical issue in a data gathering poll. It shows that this issue remains unresolved, and still a key priority and measure of a successful and impactful change. Specifically, respondents commented on the need for further live updates at bus stops and online.

We can see from poll data and Transport Scotland’s recent annual delivery plans, that some progress has been made in implementing this and that there are many more available apps, websites and mechanisms in place providing live update information - which is a successful sign of progress in some areas of accessible and available travel and journey planning information.

However, respondents noted that it is difficult to access up-to-date information, especially if you do not have access to the internet/Wi-Fi. Additionally, these websites and apps are not always accessible to a wide variety of disabled people who may have dyslexia, or visual impairments. Whilst positive progress has been made, which we can see has impacted the increase of journey satisfaction reflected in the Disability and Transport Survey (Findings from the Scottish Household Survey), nevertheless there are new issues arising which still echo the previous concern.

Indeed, when examining the baseline data established in 2017 - alongside more recent engagement exercises with disabled people - we can see that the core priorities from the perspective of disabled people have remained quite similar since the start of the ATF in 2017.

There are three strands to the factors relating to this. The first is that based on originally implemented changes and prioritized areas, issues have culminated in the same on-going priorities, but the actions and focuses within these will be different.

Many of the issues outlined in the ATF lack actionable wording, or specific measurable incremental outcome. This compounded with the lack of clear and incremental measures identified for priorities and issues, makes it difficult to ascertain progress or completion of whole issues, especially when issues require upkeep and continued work. This has resulted in issues being repeatedly raised and satisfaction rates staying approximately at same the levels.

The second is the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on the long-term impacts of changes implemented in the first five years of the framework. There was an urgent need to reprioritize and focus on the short-term implementation of new regulations and supports for disabled people travelling in Scotland during the pandemic. The shifting landscapes within travel trends, transportation needs and priorities have been severely impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic, by the cost-of-living crisis, the impacts of climate change, each of these global issues impacted disabled people’s values and behaviours when it comes to using transportation services.

The third is that priorities pertaining to Area 5 and 6 of the ATF have not yet been highly prioritized in the actions of Transport Scotland and other delivery stakeholders. This is primarily due to the high demand for other issues to be resolved and due to capacity.

We can observe that connectivity between modes was not as high a priority issue in the baseline survey, and that this has increased as a priority over the course of the last four years. The baseline survey reflects that there were less available sources to access inclusive communication formats, and no available hub for travel information.

The creation of the Accessible Travel Hub alongside the development of various passenger assistance supports such as Thistle Assistance card and App, have been positive developments in the lifespan to date of the ATF.

In relation to the question regarding ‘What changes to information would make the greatest difference to your ability to travel on public transport?’ many of these key areas are recurring and are still raised in surveys and consultation events today. These could be summarised as:

Wheelchair accessible information

Disabled people stated that useful information would be to know which buses have wheelchair accessibility, which trains have spaces, and how many spaces are available.

Up-to-date access guide

There was another suggestion to have a ‘one-stop-shop’ for information including route planners on how to reach your destination, where to change, the accessibility of the station or stop, as well as information on parking spaces for blue badge holders.

Connectivity

Other disabled passengers stated that their use of public transport could be improved by increased information on connectivity, and timetables that link to other services.

“Better linked timetabling to different modes of transport.”

“More regular service as our local bus is hourly and the bus to Irvine is hourly, these arrive within ten minutes of each other.”

The baseline survey stated that most respondents had not experienced any noticeable improvements to local transport services, it went on to comment - that from various accounts - transport providers had not made, nor intended to make, any largescale changes at this time. Very few disabled people had noticed improvements in their local transport services (17% said they had), which is not surprising, given more than half of transport providers said they had not made improvements, nor intended to.

However, we can see some meaningful changes in:

- the development of inclusive communication formats.

- passenger assistances forms provided and.

- increased satisfaction and usage of passenger assistance where it is available.

Recent priorities are more specifically about the improvement, amendment and additional provision of accessible support services and inclusive communication formats, whereas the baseline survey focuses on the implementation and initial provision of services. Potentially indicating a shift in priorities due to changing circumstances and implemented changes to accessible services.

We can surmise from looking at this alongside the key priorities raised in recent weekly poll data, webinars, and focus groups, that many of these are still on-going priorities, with issues being raised and requests for work in this area increasing since this survey was initially conducted in 2017.

National Survey Accessible Information Disabled Passenger Results Report

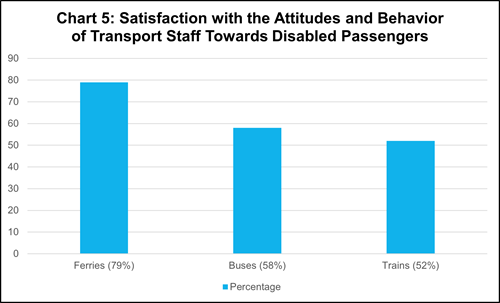

A similar survey was carried out in 2018; the “National Survey Accessible Information Disabled Passenger Results Report (Draft)” by DES. In total, 61 disabled people responded to the survey. The severe decrease in the response rate, was likely a contributing factor as to why the survey was not continued. The survey asked disabled people how satisfied they were with the attitudes and behaviour of transport staff towards disabled passengers on different modes of transport.

The following graphs represent the responses received. It shows satisfaction levels of 79% on Ferries, 58% on Buses and 52% on Trains.

*Source: The “National Survey Accessible Information Disabled Passenger Results Draft Report” (April 2018).

*Source: The National Survey Accessible Information Disabled Passenger Results Report (2018).

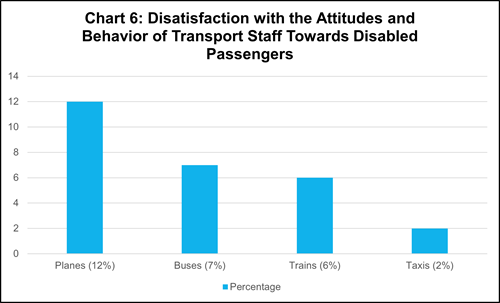

As the previous chart reflects, the highest levels of dissatisfaction were on planes - with 12% stating they were ‘very dissatisfied’ with the staff.

National Survey Accessible Information Disabled Passenger results Draft Report April 2018.pdf

The survey asked about the accessibility of information and focused on route maps and signage. Most route maps were found to be inaccessible, and most respondents found signage to be accessible.

The survey found that signage to platforms (trains) was thought to be very accessible, (22%) or quite accessible (70%) as were visual display boards: 25% very accessible; and 61% quite accessible.

The 2018 survey shows:

- Respondents were asked what would make the most positive difference to them travelling on public transport. The two most common responses were step-free access to stations (35%) and to have staff trained in disability awareness (33%).

- The survey’s questions and focuses were different from the previous baseline survey conducted which creates challenges when seeking to do a direct comparison.

- We can see that training is raised as a key issue, where previously the emphasis was on increased services, signage, timetables etc.

Disability and Transport (Scottish Household Survey)

One of the key monitors for measuring successful developments relating to the outcomes of the ATF is the Scottish Household Survey. This is published annually, with a specific section focusing on the experience and use of transport modes and travel experiences.

In 2021, the “Disability and Transport: Findings from the Scottish Household Survey” report brought together important data which supported the monitoring of the mobility gap and assisted in the evaluation of how accessible travel is improving across all transport modes.

It also highlighted trends in the most frequently used transport by disabled people in Scotland and can show what transport modes may have a larger impact.

This is a positive development in the monitoring and evaluation work of the ATF, as this provides clear annual data which can be used to track developments in the experiences of travel of disabled people in Scotland.

If this iteration of the household survey could be continued on an annual basis, the data from this could be used to monitor how ATF actions have impacted disabled people, and also where the impact has not been as effective as planned.

The data collected compared specific travel patterns and usages between disabled people and non-disabled people.

The data shows that disabled people are less likely to drive, and slightly more likely to be a car or van passenger and to take a bus to work or to their destination. When disabled people are compared to those who are not disabled, they are less likely to drive (42% to 54%), and more likely to be a car or van passenger (18% to 12%), take the bus (11% to 7%), or walk (24% to 21%).

Disability and Transport: Findings from the Scottish Household Survey

The data also shows that a lower percentage of journeys to work were undertaken by disabled people, and a greater percentage of journeys were to shops and access other key resources. [1] A smaller percentage of the journeys of disabled people were to work (12%, compared to 26% for those who are not disabled) and greater percentage of the journeys of disabled people were to the shops (32% compared to 21%).

For those whose disabilities reduced their ability to carry out day-to-day activities a lot, these discrepancies were greater (8% of journeys were to work and 35% to the shops), whereas those disabled people with no difficulty carrying out day-to-day activities, these figures were closer to those of people without a limiting condition (15% to work and 30% to the shops).

The data suggest that the emphasis on travel for disabled people is local journeys and short distance travel. Disabled adults had a shorter average (median) journey (3.2 km), than those who were not (4.5 km).

Those disabled people whose ability to carry out day-to-day activities was reduced a lot had a shorter median journey (2.9 km) than those whose ability to carry out activities was reduced a little (3.5 km).

With this data alongside testimonial data from members of DES, we can observe that short distance travel, and increased short routes to local resources is a top priority.

The household survey also shows that a greater proportion of disabled people’s journeys are at off-peak times, and this is a priority time for increased services for disabled people. On weekdays a greater proportion of disabled people's journeys are in the middle of the day, and fewer before 9.30am and after 4.30pm. For those whose disability limits activities a lot, there is an even greater proportion of travel between 9:30 and 4:30.

The biggest difference in the views of disabled and non-disabled people focused on their experience feeling safe on public transport, and how easy they found it to change between modes of transport:

- 'Feel safe and secure on the bus at night', where 58% of disabled people agreed compared to 73% of non-disabled people.

- 'Easy to change from bus to other transport', where the figures were 65% and 77% respectively.

This showed that disabled people were not satisfied with their experiences in this area. With dissatisfaction with multi-modal travel increased slightly since the 2017 baseline

This reflects that a priority in improving the experience of travelling by bus, is to focus on multi-modal journeys and linkages between parts of the journey, with a focus on increased safety on buses.

The data also reflects that buses are utilised more by disabled people than rail services. With 45% using bus travel to 18% using rail travel.

This shows that increasing use of rail for disabled people is a priority, as many of the rail services and passenger assistance options for rail have a high satisfaction rate – with respondents to polling and online events noting some positive experiences of rail recently. This is reflected further in the high satisfaction rate of the Rail Passenger Survey.

However, this finding alongside other data in the summary shows that bus travel is often more suitable for the kinds of journeys many disabled people need to carry out on a frequent basis and so whilst supporting and incentivizing the use of rail, it is equally crucial to find ways of improving new and existing bus services as well.

The Disability and Transport Household survey could be a vital tool for implementing clear indicators for progress for the implementation of many key priorities. Such as:

- ease of accessing information.

- experiences changing trains, or.

- making multi-modal journeys.

Those whose disability affected everyday activities significantly used the train less frequently than those whose activities were only affected to a lesser extent, with the number using the train in the past month 12% and 24% respectively.

When people who had used the train in the previous month were asked their views on rail services, disabled people were generally slightly less content than people who were not disabled, although differences were small for most areas. The area where the difference was highest was 'Feel safe and secure on the train at night', where 68% of disabled people agreed compared to 80% of non-disabled people.

This is similar to the responses on bus services views as well, which demonstrates that safety is still a significant concern for many disabled people using public transport.

As the Hate Crime Charter work package is developed further - and is implemented on many different transport modes - we can use this question as part of the household survey to monitor the impact this has had particularly on both bus and rail.

Overall, we see that satisfaction rates with public transport are moderately high, just slightly lower than average satisfaction rates for non-disabled people. 68% of disabled adults were very or fairly satisfied with public transport, compared to 70% of those who were not disabled. Of disabled people, those whose activities were reduced a lot were least satisfied (66% very or fairly satisfied), compared to 70% for people whose ability to carry out activities was reduced a little.

The 2021 survey also shows that there was a significant decline in disabled people flying in 2021. 29% of disabled people flew for leisure in the previous year, compared to 57% of the non-disabled population. Only 22% of people with a long-term condition that limited their day-to-day activities a lot flew, compared to 36% whose activities were limited a little.

For all limiting long-term conditions, flying for leisure was less frequent than for those with no limiting condition. Those with learning or behavioural problems (16%), a speech impairment (16%), mental health problems (17%) and difficulty seeing (18%) flew least.

This shows that support to facilitate ease and confidence in journeys from disabled people with these particular access requirements would be valuable in order to facilitate an increased number of disabled people feeling confident to fly.

This is due to many disabled people being reliant on public transport as a crucial method of accessing resources, going to work, meeting family and friends, accessing health care etc.

The increase in the distance of journeys evidence when comparing the 2017 Baseline Report and the 2021 Disability and Transport Report, could be seen as an increase in service access and quality of service issue, resulting in increased travel and confidence in undertaking longer journeys - and this is something that could be used as an indicator moving forward, taking into account learnings from the 2017 report ‘Disabled people’s travel behaviour and attitudes to travel.

Disabled people’s travel behaviour and attitudes to travel (publishing.service.gov.uk)

One aspect that this report employed was the implementation of a grading system of different disabilities and access requirements. This graded different forms of disabled people’s experiences in order to analyse travel trends. The Disability and Transport Survey also makes a separation and asks those completing the survey to state the kind of disability they have.

As the work within this 2017 report showed, it is of significant benefit to collect specific data, which gives more insight into the individual’s experience and how this effects their travel/transport decisions.

There is an opportunity within the continuation of the Disability and Transport Survey to develop from the work of this 2017 report, providing further options for those participating in the survey to provide insights into their particular barrier to travel, and gathering more data which focuses on behaviour and driving forces which impact on the values of and travel trends of disabled people.

Consultation

It is clear from the information available via archives, what is recorded publicly in Transport Scotland’s annual delivery plans, as well as via associated resources - including the Accessible Travel Hub - we can see that active consultation has been achieved recently, with webinars, consultation events, stakeholder engagement exercises in 2021 and 2022.

However, some of the recent feedback gathered in the ATF poll series shows that whilst disabled people feel - to some extent - engaged with and consulted about their current travel priorities, they often feel as though they are repeating the same issues without experiencing more impactful change.

Accessible Travel Hub and weekly polls

The Accessible Travel Hub was set up as part of the work of the ATF, to collect information, travel, and transport resources from disparate locations in order to mitigate confusion and discrepancies and to create one central location where this information could be collected and accessed.

From quarterly reports submitted to Transport Scotland on its performance, webpage views continue to increase.

A recent focus group convened in March 2023 gathered feedback on the Accessible Travel Hub, with some of the findings being:

- That the resources on the Hub were still seen to be very beneficial and used frequently.

- That the Hub should be kept up to date with recent information where possible, and that there was potential to collaborate with transport providers to ensure that new information and travel resources are being communicated to disabled people using these services and modes, increasing the reach of this information, and collecting it all in one place of easy cross referencing and access.

- To facilitate frequent updates to the Hub, it was suggested that transport providers have a central point of contact through Transport Scotland or DES, so that new information could be added easily.

- There was also a further suggestion to involve Access Panels and gather local information on transport to be included as well.

- That the Hub could become a space which hosts training resources for staff and transport providers, and that it would also be of benefit to build on the positive news section and highlight and record further examples of best practice relating to transport and travel.

- The web page still continues to host useful information for thousands of disabled people visiting the page, however the information within the hub does not update often.

However, through the most recent Weekly poll series of questions pertaining to the ATF - specifically communication - many disabled people still struggle with the disparate nature of travel information, having to use multiple websites and apps with inconsistencies of information which can be a barrier to journey planning and impact their confidence and likelihood of travel.

Weekly polls

The DES weekly polls have been an incredibly well received and a successful component of the DES website and has become a vital resource for feedback and recent lived experience testimonies. With a wide range of organizations and government bodies collaborating with DES to put together poll questions, with the feedback from participant responses going on to shape and implement changes to their work.

Particularly through the Covid-19 pandemic the DES weekly polls were a useful way to communicate with disabled people and to gather timely feedback and responses to key topical issues, such as face covering exemptions, hate crime, and transport experiences.

A key development with lived experience data collection moving forward, will be to find ways of collecting further details on the individuals perspective, their locality, their access requirements, and how this intersects with their lived experience and the feedback they’re sharing.

These weekly polls have been vital in assisting to form a clearer picture of the priorities, values, and experiences of disabled people both currently, and over the past three years across the changes of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Another positive step in the area of monitoring by Transport Scotland was conducting a bus station survey (2021) and taxi survey (2021), which provided useful baseline data. It is recommended that this work be continued. This would continue developing information to support needed work in both the training priority and the taxi priority.

In the archives of the ATS Group’s history, we can see that the original areas and issues identified in the framework were broken down into different work packages. These were structured into 13 work streams, each work stream related to a cluster of priority actions and intersected with one or two of the six areas of the framework.

Attached to each stream was a series of commitments, a list of outputs, actions for the work stream, in addition to listing who owned or who was responsible for the work stream of the ATF. Members, according to their knowledge and interests. A low-level action plan was produced as part of the work of the ATS Group which was used to steer the work conducted over the first few years of the framework.

MACS Annual Report 2018 (pdf) pp-2

We can see from early project documents published, that MACS are another key stakeholder that is crucial to both the implementation and the monitoring of the framework. We can observe that MACS still carry this management practice forward and have assigned MACS members to certain work streams, following these initial draft planning documents in 2017/18.

Other than in MACS reports, which delineate how they implement and align themselves with work streams within the ATF, there is a data gap identified between the initial planning, action plans, and driver maps drafted in 2017 and 2018, and previous annual delivery plans.

This review could find no available information evidencing whether these driver map or action plan management practices have been upheld, or whether the 13 originally mapped out work streams are still used as a monitor and guide for all the stakeholders involved in delivery.

The archiving and storing of many of these reporting documents and management processes system appear to have been negatively impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic and additional internal factors to Transport Scotland. Through background research some of these early driver maps and monitoring documents have been found, however it is recommended that further work be done to map a timeline of planning and reporting documents.

It is advised that by locating all 13 work stream driver maps originally created in collaboration with other key stakeholders involved in the ATS group that these could be used as the basis for a reflection on progress made and a guide for moving forward.

However due to the identified gaps in the ATF’s archiving and reporting history, it is difficult to ascertain how effective this evaluation and monitoring could be as we were unable to find current evidence within the information available whether this practice was continued on an annual basis.

In 2018 we can see these initial reporting strategies worked positively:

- MACS redefined and refocused the framework of the committee. This included an overarching Planning and Strategy Workstream that incorporates all modal workstream leads.

MACS has agreed to assist with Work Package 2 (Assistance During the Journey) and Work Package 8 (Information) of the Accessible Travel Framework.

We can see from some 2018 project documents, that multimodal journeys and integration between modes of transport were acknowledge as a priority moving forward.

In the first Accessible Travel Annual Delivery Plan 2019-2020 (pdf) was produced by Transport Scotland as potentially a new method of updating and delineating the work being done. With work streams now being categorized as priorities to be acted upon, and a series of actions attached to each one. It is stated in this plan that it updates on the progress since 2016. This first plan document spans the first three years of progress and looked forward to the end of 2020.

The plan was put together in collaboration with Transport Scotland’s accessible transport partners, the 15 public appointees who make up the Mobility and Access Committee for Scotland (MACS), DPOs, Access Panels and transport operators.

Example achievements stated in the 2019 Transport Scotland annual delivery plan:

- Advance noticed for passenger assistance reduced by 50%.

- The advance notice required for ScotRail passenger assistance has reduced by 50% from four hours in 2016, to two hours today. and we anticipate a further 50% reduction by around 2021 – the lowest in the UK – this compares with most of the other UK operators requiring 24 hours. ScotRail is reporting passenger assistance requests are up by 16.7% in 2017-2018. Pp-3).

- The plan also evidences improvements in aviation.

- A Ferries Accessibility Fund totalling £1 million financed by both Transport Scotland and transport operators, has seen substantial improvements since 2014 on Scotland’s ferries and terminals, such as: accessible doors and changing places toilets being installed in some terminals and ferries, training including guide dog and dementia is being rolled out for staff annually.

- The annual delivery plan states that these documents will be co-produced and used as a guide to steer the next year’s work whilst reflecting on the previous.

In the second annual delivery plan published by Transport Scotland in 2021, we can see that the language of the delivery plan production shifts to a consultation model, working with the ATS group, and DES consultation exercises.

The current priorities have been agreed through an extended period of engagement with disabled people which has involved one-to-one meetings, group discussions with various organisations from the ATS group, a series of webinars hosted by DES and polls on a range of subjects that are important to disabled travellers which have helped to increase the understand of the impact of the pandemic on journeys, including how confidence to travel can be strengthened.

Accessible Travel Annual Delivery Plan 2021-22 (pdf)

Each of the eight thematic priority areas within this year’s Delivery Plan are taken from the ten-year Accessible Travel Framework and are underpinned by quality improvement methodology in partnership with the Scottish Government’s Improvement Team.

As an addition, we can see that the DES Weekly polls have become a useful way of gathering more immediate and specific data on a variety of travel and transport related topics.

We can see that up until February 2020 Accessible Travel check-in events took place hosted by DES across different areas of Scotland. The summary reports for these events evidence that these events were reformatted legacies of the Longitudinal Progress Evaluation Group proposed in the original framework’s development. These can be seen as positive exercises, with feedback after the events noting that they would like these to be recurring check-ins.

However, we can see that as work has progressed on the priority actions outlined in this document, the monitoring and evaluation work has not been equally prioritized on a continual basis, due to lack of resources and support.

It is a vital component of successfully working towards these outcomes to research, compile, and archive both the history of how this framework has been planned, managed, and experienced by disabled people. This would not only support the work of Transport Scotland as they work to facilitate resolving these priority issues, but also would ensure that the continuous monitoring and evaluating work of the Accessible Travel Framework is conducted with a similar ethos of co-production and collaboration that the original document was made with.

We can see that many of the original indicators have been continued and utilized to inform reporting such as the annual delivery plans and the progress reports. That said, we can also observe that qualitative measures have not been as clearly continued and implemented across all the workstreams carried forward.

Engaging with the format of the ADP published previously, some of the progress indicators are not always made clear in the reporting, not showing which of the 48 issues identified have been completed. It can also be difficult to ascertain what a measure of progress or completion can be in these areas. It is recommended that if this format is to be considered then an appendix is attached which outlines which issues are in progress, which are complete, and which have not been started yet.

The actions required to deliver the vision, cannot just be presented, or achieved centrally, some actions are more appropriately addressed at local and regional levels, according to personal and geographical issues.

Going Further: Scotland’s Accessible Travel Framework (pdf)

Subsequently as part of these monitoring actions Transport Scotland have developed a method of updating on the priorities they are currently focusing on and what has been done so far in some of these areas. These have been published in the form of annual delivery plans, the first one was published in 2019 spanning 2019 – 2020, and the second published in 2021 spanning 2021 – 2022.

The indicators raised in the ADP focus on increased awareness and increased usage, but in order to evaluate impact and progress the indicators need to focus on the user experience. From the original intentions of the ATF monitoring, there should also be qualitative indicators. It is evident from assessing many of the surveys, polls, and event summary reports, that there is a lack of continuity to the questions being circulated to disabled people about their experiences of travel, making it difficult to find key through lines of progress being made on specific issues.

With the quantitative measures implemented, which all run on a predominantly annual basis - with the exemptions of the Covid-19 related impacts - we can see that for the most the part, the questions and the format stays broadly the same and becomes much more effective to work with the data comparatively.

Review of transport accessibility statistics

The report was part of a wider body of work looking into the accessibility of modes of data collection, and in particular how statistics were/are being gathered specifically pertaining to the accessibility of travel.

The Office of Statistic Regulation (OSR) published a report in February 2022 which further develops this work. The Review of Transport Accessibility Statistics focused on ascertaining whether statistics gathered relating to accessibility and transport were meeting user needs.

The review found that for a variety of reasons the data collected was not consistently meeting the user needs across the UK. The review noted that it did not identify a significant demand in Scotland beyond internal data collection points, and further noted that other organizations consulted also relied on their own qualitative data collection channels.

The OSR review lists some key recommendations based on its findings. These recommendations align with the work of the ATF, and more widely with this newly developed body of monitoring and evaluation work begun with this report and project.

One of the key recommendations from the review was the development of lived experience of disabled people:

“By moving to a model of defining disability that reflects social barriers, not just impairments, policy makers will better understand the experiences of individuals”

This report suggested that as monitoring and evaluation plans which were in development to support the remaining work of the ATF’s life span and beyond, that all take into consideration the recommendations of the OSR’s review and carry forward some of these recommendations when implementing changes to monitoring and evaluation systems of the ATF.

Similar to the findings of this review into the ATF monitoring and evaluation systems, this 2022 review noted that Transport Scotland should consider seeking user engagement to find ways of supporting local understanding and policy development.

The view noted that clarity and transparency between policy departments, analytics professionals, and users was of the upmost importance. Noting that they should find effective ways of being clear and open with users about how they and the public will be able to evaluate impacts of their transport strategies.

The approach of this review echoes this recommendation, as this report aims to present information on what systems have been and are currently in place. Furthermore, this report draws on lived experience data from disabled people in Scotland, reflecting on the information shared to consider the most effective ways of measure progress and monitoring impacts and meaningful change in ways that considers and responds to current priorities, values, and experiences of disabled people in Scotland.

Similar to the findings within the OSR review, this review finds that Transport Scotland - alongside many other policy departments across the UK - require to focus their attention on the practical amalgamation (integration) of lived-experience data into how progress is indicated and measured, in relation to strategies and implementation plans.

The 2022 OSR review shares similar findings to the ‘Disabled people’s travel behaviour and attitudes to travel’ (2017) report, both of which found that the behaviours and driving factors to the decision-making process that disabled people go through when planning travel, would help inform and provide more accurate information about travel and transport trends, and the needs of disabled people in relation to transport strategies.

This review begins this journey, laying out a series of key recommendations which can be trialled and put into action to work towards meetings these OSR recommendations surrounding lived experience data.

The OSR review notes that they did not find a significant need for more external data, as they found that additional data collection points in partnership with stakeholder organisations such as MACS, were supporting and meeting these requirements. It further noted that these were predominantly qualitative forms of data.

This reflects a positive step in Transport Scotland’s partnership with organizations collecting and working with qualitative data and investing time and resources into consultation and data collection channels which prioritize lived experience.

The OSR review aligns with the ethos of this review, which is to highlight and draw from lived-experience data as the first point of call when planning, implementing policies and devising systems of change.

The OSR review also noted that publishing not only the data but also the metrics and infrastructure of progress measurement to enable those interested/involved to carry out their own analysis and track progress would be of benefit.

This review agrees and reflects on testimonial data from disabled people in recent months, that many of those involved in polls, consultation exercises and focus groups were not aware of how this on-going work was being monitored since its original publication in 2016, with many individuals commenting that they were not aware of what progress has been made, and how it is being measured.

The DES weekly polls and other engagement exercises indicate that many disabled people feel that they have not been consistently informed of monitoring and evaluation systems or progress or changes being implemented. New data and data collections systems need to be more consistently related and it needs to directly correspond and map onto the priority action moving forward, with this process being done in consultation with those who use the services or experience these barriers to mobility.

Whilst there are some opportunities for feedback consultation during planning and monitoring project stages, lived-experience testimonial data shows that there is further work to be done to provide truly inclusive consultation opportunities, consistently across various regions within Scotland. Consultation and co-production requires to be monitored and evidenced through project plans moving forward with the work of the ATF.

This compounded with many other channels of feedback from disabled people across the last four years, which articulate confusion and lack of awareness of impactful change across some key areas of the ATF’s identified issues.

This could become a new key function of the Accessible Travel Hub, and some of regional events and online events which are staged across different regions of Scotland.

This underpins the recommendation from this review which is to develop systems of measures and indicators developed with and shared with disabled people, which can inform and guide implementation plans, and assessments of progress towards completing the priorities of the ATF.

As mentioned in the background to the ATF, a longitudinal study was proposed as another key monitor of progress throughout the framework’s lifespan. It is evident from user experience data gaps that this longitudinal study was an important component of the qualitative progress indicators, and not having this continued data has impacted the review’s ability to reflect on the accumulated impact of the framework’s implemented work streams since 2016.

Both this UK-wide OSR review, and smaller reports and reflective exercises undertaken by Transport Scotland are incredibly positive steps towards meeting these goals and working towards closing the mobility gap with an ethos and systems in keeping with the beliefs of the ATF - prioritizing consultation and lived experiences of disabled people as the central guiding force which effects the priorities and action plans implemented.

Disabled people’s travel behaviour and attitudes to travel

We can see from research that similar recommendations and practices pertaining to gathering behaviour and emotion-driven data sets, which filters and categorizes data trends by creating different categories of disability, allow for further detail within the travel trend analysis. A report was developed and published in 2017, one year into the ATF’s lifespan, which develops this research.

Disabled people’s travel behaviour and attitudes to travel (pdf)(gov.uk)

The report evidenced gaps in data collection systems, where insufficient detail was being collected pertaining to the individuals experience and how factors in individual lives impact travel and transport decisions and therefore need to be woven into the data collection and analysis.

The aim of ‘Disabled people’s travel behaviour and attitudes to travel’ (2017) was to begin to address gaps in the evidence base on the travel behaviour of people with disabilities, drawing on recent secondary analysis of five key surveys. The work of this report became another way to consider the baseline data with the particular focus being on attitudes and behaviours of disabled people.

This report also articulated a key gap in the knowledge base which persists today. In comparing some of the observations from the 2017 report and the 2022 report - alongside analysis conducted as part of the research for this review - we find that this key issue pertains to the ability of Transport Scotland, and other stakeholders working with the ATF. In essence the issue stems from not only a lack of data which pertains to particular areas or work packages, but also from a lack of data which separates its information with enough detail to provide data to conduct a meaningful impact evaluation. Specifically, to provide an accurate reflection on the trends of how different disabled people are travelling and the specific regional and individual issues pertaining to travel.

More recent reporting, such as the ‘Disability and Transport Report’ (2021), began to implement some of these practices, such providing additional options for the level of barrier that the disabled person experiences due their particular disability. However further information such as age and region would provide further clarity.

The 2017 report acknowledges the gaps between travel trends within data collected from disabled people. These gaps within the body of data - which shows the wider picture of disabled people’s travel trends - mean that vital pieces of information which create the set of conditions which relate to a disabled person’s travel habits and what the barriers, priorities, and values they have, reflect that important data which could help inform action plans and evaluation, are not being recorded via many existing annual and bi-annual data collection channels utilized as original indicators for monitoring the progress of the ATF’s work.

The 2017 report also promoted the idea of longitudinal data collection, which was a component of the ATF’s monitoring implementation plan which was unfortunately discontinued.

Whilst this review finds clear indications that the initial longitudinal study was deemed unfeasible to continue, that this (compounded with the Covid-19 pandemic), further indicated that they would not be feasible to reinstate.

However longitudinal studies, or data collection which upholds continuity across a broad range of regions and a wide spectrum of disabled people with differing experiences, would be one of the most effective ways to chart progress and impact of the ATF work packages across Scotland.

The 2017 report notes that the context of someone’s journey, their characteristics (i.e., their particular access requirements; geographical locality), needs to be considered as a wide spectrum, rather than the standard approach, which collates data from a wide range of disabled people without having the additional questions in place to mediate them.

The report notes that the individual disabled person’s barriers to travel and their personal experience and access needs range vastly and these need to be taken into consideration when considering priorities and action plans moving forward.

Whilst this review pushes for these considerations and practices within data collection and analysis of disabled people and transport data, this is supported by the same observations made within the OSR review, focusing on the need for lived experience data collection and analysis,

The inclusion of more consistent and detailed measures of disability could maximise the future ability of researchers to synthesize findings from different surveys already in place would be useful, providing more in-depth insights into travel needs and trends.

Within the implementation of these goals and the monitoring of progress, consideration needs to be made and evaluation/monitoring metrics need to be put in place which accounts for:

- the travel trends of disabled people.

- access requirements and.

- the range of factors which contribute to disabled people’s behaviours when it comes to travel.

Monitoring and evaluation group

A further way that these considerations can be implemented in the remaining lifespan of the ATF, could be through the work of the recently established Monitoring and Evaluation Group set up by MACS and Transport Scotland in 2023.

It is proposed that the group would contain representatives from:

- Transport Scotland Analytical Team.

- Mobility and Access Committee for Scotland.

- Disability Equality Scotland and.

- Transport Scotland Accessible Travel Team.

This recent development signifies a positive development towards implementing some of the recommendations from this review.

The initial aim of this group is to monitor and review progress as it develops towards the collective goal that all participating organizations have, which is to close the mobility gap and make transport more accessible by removing barriers experienced by disabled people. The group notes that a specific aim within this is to improve monitoring and evaluation and research regarding disability and transport and its relationship to NTS2 and the ATF.