Volume 1, Chapter 18 - Human Health

Summary

This chapter assesses the impact of the A9 Dualling Programme: Pass of Birnam to Tay Crossing on human health with particular focus on the communities of Dunkeld, Little Dunkeld, Birnam and Inver.

The assessment has followed Design Manual for Roads and Bridges LA 112 ‘Population and human health’ guidance, supported by assessment criteria from the Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment. The assessment has drawn on information from other Environmental Impact Assessment topic chapters as well as from community engagement and desk studies. The following health determinants have been assessed:

- community, recreational and education facilities and severance/separation of communities from such facilities;

- landscape amenity and green/open space and severance/separation of communities from such facilities;

- healthcare facilities and severance/separation of communities from such facilities;

- community identity, culture, resilience and influence;

- spatial characteristics of the transport network and usage, including the surrounding road network, Public Rights of Way (including bridleways), cycle ways, non-designated public routes and public transport routes;

- air quality;

- noise and the ambient noise environment;

- sources and pathways of potential pollution;

- road safety; and

- flood risk.

The significant negative health effects identified relate to construction impacts on noise and the ambient noise, and road safety for vulnerable groups. Disruption of the transport network could have a wider impact on people in the area through safety concerns for commuting or recreational walkers, wheelers, cyclists or horse riders (WCH). Temporary diversions of pedestrians and cyclists may increase the likelihood of collisions with traffic if not appropriately managed and the presence of construction works could also result in a reduction in perceived safety. This localised disruption to pedestrian and cycle routes, as well as to traffic on the A9 and connected road network, would potentially affect access to community, recreational and education facilities, green/open space and healthcare facilities. These are interrelated impacts on transport and access to community and recreational resources. Construction noise and traffic would also affect local amenity. In terms of population health, construction noise impacts could result in a temporary change in quality-of-life with many of those exposed being in residential properties or those wanting to enjoy the outdoor natural heritage of the area. Vulnerable groups may include those with autism spectrum disorder or who have mental health conditions, or shift workers trying to sleep during the day, who are more likely to have a high sensitivity towards noise. The identified pathways to health outcomes from these impacts include reduced physical activity, social interaction and loss of amenity, which may have a negative impact on physical and/or mental health and social wellbeing. While the general population is relatively healthy and likely to be able to adapt, vulnerable groups may have less capacity to adapt to the construction phase impacts and are more likely to suffer adverse health outcomes in the short-term. Mitigation for impacts on traffic, accessibility, land use, noise and air quality are identified in other relevant chapters, while the standard mitigation in the form of the appointment of a Community Liaison Officer, a liaison team and dedicated helpline, is considered particularly important in supporting the affected communities.

For the operation phase, vulnerable groups have the potential to significantly benefit from accessibility and safety improvements to the A9 road and some local routes for WCH. These improvements are expected to reduce physical barriers as well as safety concerns, which may help vulnerable groups in particular to better access community and health facilities, and areas of recreational value. This should support better health and wellbeing. Potential negative effects of the operation stage relate to risks of windblown soil dust and fibres identified in the geology and soils assessment (Chapter 13) and an increase in flood risk for a small number of properties (Chapter 19) which would have potential consequential effects on the health and wellbeing of those affected. However, with proposed mitigation in place these impacts would be reduced to not significant, removing the likelihood of significant health effects.

While there would be significant negative effects on health during the construction stage in the short term for those most affected by noise and disruption, during operation, the significant effects are expected to be positive, relating to improved safety and accessibility.

Introduction

Overview

- This chapter presents the Design Manual for Roads and Bridges (DMRB) Stage 3 Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for the A9 Dualling Programme: Pass of Birnam to Tay Crossing (hereafter referred to as the proposed scheme) in relation to impacts on human health.

- The World Health Organization (WHO) defines human health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ (WHO, 1948). Therefore, this assessment addresses both physical and mental health.

- The assessment considers the potential impacts of the proposed scheme on health determinants, which are the range of personal, social, economic and environmental factors that determine the health status of individuals or populations. The assessment focuses on effects on population health which is defined as the health outcomes of a population, including the distribution of such outcomes within the population (Kindig and Stoddart, 2003), rather than the health of individuals (which is a clinical matter).

- This chapter has drawn on the assessments of residual effects from other EIA topics. Output from the following EIA topics has been considered in the human health assessment:

- Chapter 8 (Air Quality).

- Chapter 10 (Landscape).

- Chapter 11 (Visual).

- Chapter 13 (Geology and Soils).

- Chapter 15 (Noise and Vibration).

- Chapter 16 (Population - Land Use).

- Chapter 17 (Population - Accessibility).

- Chapter 19 (Road Drainage and the Water Environment).

- Chapter 12 (Biodiversity) and Chapter 14 (Material Assets and Waste) are not referenced within this assessment as it is considered that impacts arising from these topics would not have likely significant effects on human health. Chapter 20 (Climate) is also not referenced as localised impacts that could potentially occur as a result of climate change (i.e. flooding) are captured within Chapter 19 (Road Drainage and the Water Environment).

- This chapter does not seek to repeat text or replicate data from other EIAR chapters but instead uses the information to conclude how changes to health determinants could lead to different health outcomes for communities as a result of the proposed scheme.

Legislative and Policy Background

- This section provides an overview of the relevant national, regional and local planning policies for human health and wellbeing.

- The inclusion of the human health topic as part of EIA is a requirement of the EIA Directive (85/337/EEC) (hereafter referred to as the EIA Directive) and The Roads (Scotland) Act 1984 Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2017 (hereafter referred to as the 2017 Roads EIA Regulations). Improving public health and wellbeing in Scotland is the focus of a number of government strategies. In 2018, a Review of Public Health Priorities for Scotland (Scottish Government, 2018) was published which stated that Scottish people have a lower life expectancy than their counterparts in Western Europe. The report set out four priorities, including reducing health inequalities as a primary objective, and also recognising the importance of initiatives such as community gardens and preserving and enhancing walking/cycling routes and greenspace for encouraging physical activity.

Scotland’s National Performance Framework

- In June 2018, the Scottish Parliament introduced the National Performance Framework (NPF), which sets out the vision for national wellbeing in Scotland across a range of economic, social and environmental factors. The NPF sets out 11 ‘national outcomes’. The NPF national indicators have been considered in this assessment as policy priorities of relevance to health and wellbeing.

Transport Scotland’s National Transport Strategy 2

- Scotland’s second National Transport Strategy (NTS2) was published in 2020 and sets out the vision for the country’s transport system, underpinned by four priorities each with three associated outcomes, to be at the heart of decision-making. One of the priorities and associated outcomes is specifically related to health and wellbeing, as follows:

- ‘Improves our health and wellbeing

- Will be safe and secure for all

- Will enable us to make healthy travel choices

- Will help make our communities great places to live.’ (Transport Scotland, 2020)

- NTS2 identifies safety as a priority for the transport system as road incidents can have a significant negative effect on society, with those living in deprived areas being worst affected. Rural areas are also highlighted as a key area for improving safety due to the challenges associated with the more poorly maintained footpath networks and roads.

- NTS2 sets out that active travel is one of the most effective ways to secure the recommended 30 minutes of moderate activity per day to reduce obesity and other health issue related to inactivity. NTS2 highlights the importance of children learning healthy behaviours such as walking or cycling when they are at a young age.

Summary of Sustainable Development and Planning Policies of Relevance to Human Health

- Table 18.1 sets out the key planning policies of relevance to human health and the level at which they are adopted. Section 18.7 provides a summary of the assessment of policy compliance for this chapter and an assessment of the compliance of the proposed scheme against planning policies and plans is also reported in Appendix A3.1 (Plans and Policies).

Table 18.1: Overview of Key Planning Policy Relevant to Human Health

|

Policy |

Description |

Key Points |

|

International |

||

|

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, 2015) |

The SDGs comprise 17 Goals to Transform Our World. They are a call for action by all countries to promote prosperity while protecting the planet. |

‘Goal 3: Ensure Healthy Lives and Promote Well-being for All Ages’ focuses on eradicating diseases and addressing many different and emerging health issues. Health is essential for sustainable development and most of the other goals have an interrelationship with determinants of health. As a result, arguably all of the SDGs can be associated with health in some form. However, some other goals of note are SDG 5 (gender equality), 8 (decent work and economic growth), 10 (reduced inequalities) and 11 (sustainable cities and communities). |

|

National |

||

|

Scotland’s Fourth National Planning Framework (NPF4) (Scottish Government, 2023a) |

NPF4 supports the SDGs and national outcomes and sets out the National Spatial Strategy to improve people’s lives by making sustainable, liveable and productive places. |

In relation to health, the policies outlined in the strategy include:

|

|

Scotland’s National Performance Framework (Scottish Government, 2019) |

NPF sets out ‘national outcomes’ which align with the SDGs and aims to increase the wellbeing of people living in Scotland, amongst other aims. |

The ‘national outcomes’ describe the kind of Scotland it aims to create. In relation to health, the outcomes are as follows:

|

|

Public Health Priorities for Scotland (Scottish Government, 2018) |

This plan sets the national public health priorities for Scotland. |

Priorities relevant for the design of the Scheme include: Priority 1: A Scotland where we live in vibrant, healthy and safe places and communities. Priority 3: A Scotland where we have good mental wellbeing; Priority 5: A Scotland where we have a sustainable, inclusive economy with equality of outcomes for all; Priority 6: A Scotland where we eat well, have a healthy weight and are physically active. This priority promotes physical activity through nature-based initiatives and the maintenance of active travel network. These priorities reflect a holistic approach to public health addressing not only healthcare issues but also the wider determinants of health. This assessment considers wider determinants of health. |

|

Mental Health Strategy 2017 – 2027 (Scottish Government, 2017) |

Sets out 40 initial actions to better join up mental health services, refocus them and deliver them when they are needed. |

The Strategy sets out a guiding ambition for mental health ‘…that we must prevent and treat mental health problems with the same commitment, passion and drive as we do with physical health problems. That means working to improve: This strategy has now been replaced by the Mental Health and Wellbeing strategy below, but this strategy is still relevant due to other policy still being based on this older version. For example, this mental health strategy has informed the Perth & Kinross Mental Health and Wellbeing Action Plan outlined below. |

|

Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy (Scottish Government, 2023b) |

This Strategy lays out the long-term vision and approach to improving the mental health and wellbeing of everyone in Scotland – including consideration of the role of poverty, housing, employment and communities. |

The Strategy takes an outcome focussed approach with three key areas of focus: ‘Promote positive mental health and wellbeing for the whole population, improving understanding and tackling stigma, inequality and discrimination; Prevent mental health issues occurring or escalating and tackle underlying causes, adversities and inequalities wherever possible; and Provide mental health and wellbeing support and care, ensuring people and communities can access the right information, skills, services and opportunities in the right place at the right time, using a person-centred approach.’ There are nine summary outcomes outlined in the Strategy: 1. ‘Improved overall mental wellbeing and reduced inequalities. 2. Improved quality of life for people with mental health conditions, free from stigma and discrimination. 3. Improved knowledge and understanding of mental health and wellbeing and how to access appropriate support. 4. Better equipped communities to support people’s mental health and wellbeing and provide opportunities to connect with others. 5. More effective cross-policy action to address the wide-ranging factors that impact people’s mental health and wellbeing. 6. Increased availability of timely, effective support, care and treatment that promote and support people’s mental health and wellbeing, meeting individual needs. 7. Better informed policy, support, care and treatment, shaped by people with lived experience and practitioners, with a focus on quality and recovery. 8. Better access to and use of evidence and data in policy and practice. 9. A diverse, skilled, supported and sustainable workforce across all sectors.’ |

|

Strategic Transport Projects Review 2 (STPR2) (Transport Scotland, 2022) |

The STPR2 will inform transport investment in Scotland for the next 20 years (2022-2042) by providing evidence-based recommendations on which Scottish Ministers can base future transport investment decisions. |

The outcomes from STPR2 will:

STPR2 makes 45 recommendations that focus investment on sustainable transport options. The following are considered to be of particular benefit to the Tay Cities region:

|

|

Local |

||

|

Perth & Kinross Council Local Development Plan (LDP) (Perth & Kinross Council, 2019) |

Perth & Kinross Council LDP sets out the overall spatial planning policy for the local authority area. |

Policy 54: Health and Safety Consultation Zones ‘In determining planning applications for development within the Pipeline Consultation Zones identified on the proposals, inset maps and Appendix 3, the Council will seek and take full account of the advice from the Health and Safety Executive and the facility’s operators and owners. The Council will also seek the advice of the Health and Safety Executive and the facility’s operators and owners on the suitability of any proposals for a new notifiable installation within the Plan area or any proposal within the consultation zone of any other notifiable installation.’ (p.91, Perth & Kinross Council, 2019) Policy 52: New Development and Flooding ‘Within the parameters as defined by this policy the Council supports the delivery of the actions and objectives to avoid an overall increase, reduce overall, and manage flood risk as set out within the relevant SEPA Flood Risk Management Strategies and the Local Flood Risk Management Plans. There will be a general presumption against proposals for built development or land raising on a functional flood plain and in areas where there is a medium to high risk of flooding from any source, or where the proposal would increase the probability of flooding elsewhere. In addition, built development should avoid areas at significant risk from landslip, coastal erosion, wave overtopping and storm surges.’ (p.86, Perth & Kinross Council, 2019) Policy 56: Noise Pollution ‘There will be a presumption against the siting of development proposals which will generate high levels of noise in the locality of existing or proposed noise sensitive land uses and similarly against the locating of noise sensitive uses near to sources of noise generation. In exceptional circumstances, where it is not feasible or is undesirable to separate noisy land uses from noise sensitive uses, or to mitigate the adverse effects of the noise through the negotiation of design solutions, the Council may use conditions attached to the granting of planning consent, or if necessary planning agreements, in order to control noise levels. A Noise Impact Assessment will be required for those development proposals where it is anticipated that a noise problem is likely to occur.’ (p.91, Perth & Kinross Council, 2019) Policy 57: Air Quality ‘The Council has a responsibility to improve air quality. The LDP does this by seeking to prevent the creation of new pollution hotspots, and to prevent introduction of new human exposure where there could be existing poor air quality. The LDP extends support to low emission technologies for both transport and energy production. As well as aspiring to improve air quality, the policy also aspires to eliminate the gradual worsening in air quality that is caused by the cumulative impact of many small developments. Within or adjacent to designated Air Quality Management Areas, where pollutant concentration are in excess of the national air quality objectives and may pose a risk to human health, development proposals that would adversely affect air quality may not be permitted. There is a presumption against locating development catering for sensitive receptors in areas where they may be exposed to elevated pollution levels. Any proposed development that could have a detrimental effect on air quality, through exacerbation of existing air quality issues or introduction of new sources of pollution (including dust and/or odour), must provide appropriate mitigation measures. The LDP expects that some type of mitigation of air quality impacts will be required for all but the smallest developments. Best practice design measures should therefore be considered early in the design and placemaking process. Proposals and mitigation measures must not conflict with the actions proposed in Air Quality Action Plans.’ (p.92, Perth & Kinross Council, 2019) Policy 58A: Contaminated Land ‘The Council’s first priority will be to prevent the creation of new contamination. Consideration will be given to proposals for the development of contaminated land, as defined under Part IIA, Section 78A(2) of the Environmental Protection Act 1990, where it can be demonstrated to the satisfaction of the Council that appropriate remediation measures can be incorporated in order to ensure the site/land is suitable for the proposed use and in order to ensure that contamination does not adversely affect the integrity of a European designated site(s). Informal pre-application discussions should take place at the earliest opportunity between the Council, the developer and any other interested parties in order to help identify the nature, extent and type(s) of contamination on the site (including any source, pathways, receptor links) and the most appropriate means of remediation. The Council may attach conditions to the granting of planning consent to ensure that these remediation measures have been completed prior to the commencement of any works on site and/or the occupation of any new units. The Council will adopt the ‘suitable for use’ approach as advocated by Scottish Government Statutory Guidance when dealing with proposals for the development of contaminated land.’ (p.95, Perth & Kinross Council, 2019) |

|

Mental Health and Wellbeing Action Plan (Perth & Kinross Council, 2018) |

The Plan had been developed to direct services towards new ways of working to ensure people get the support they need at the right time and is strategically aligned to National Health and Wellbeing Outcomes. |

The Plan sets out local mental health and wellbeing outcomes, which are guided by the broader national outcomes. Examples of these local outcomes are as follows (the list is not exhaustive):

|

|

A9 Dualling Programme Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) (Transport Scotland, 2013) |

The SEA aimed to integrate environmental considerations into the very early stages of programme development for the A9 Dualling Programme. |

The SEA highlighted the following as considerations for population and human health. The A9 Dualling Programme was considered to be an opportunity to improve road safety, reduce accident severity and improve connectivity between Inverness, Perth, local communities and the central belt. The SEA also flagged access to/from the route, particularly regarding walkers, cyclists and horse riders, the Cairngorms National Park and other recreational facilities, as key challenges. |

Approach and Methods

- This section explains the approach used to establish the baseline conditions and assess the potential changes to health outcomes and includes a summary of the relevant guidance used in the human health assessment.

Overall Approach

- The assessment follows DMRB LA 112 ‘Population and human health’ guidance of the effects of proposed trunk road schemes on human health (hereafter referred to as DMRB LA 112) (National Highways et al., 2020). The assessment uses the Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment (IEMA) Guide to Determining Significance for Human Health in Environmental Impact Assessment (Pyper et al., 2022a) in the assessment of likely significant effects and considers the health determinants outlined in the IEMA Guide to Effective Scoping of Human Health in EIA (Pyper et al., 2022b). The six stages of the human health assessment which have been developed for this EIA are outlined in Diagram 18.2.

Background

- During DMRB Stage 2, in response to community consultation, a Wellbeing Assessment was undertaken using a bespoke approach and methods. The community objectives (as shown in Table 18.2) were mapped against wellbeing indicators drawn from Scotland’s National Performance Framework (refer to Table 18.1) and assessed against the output from relevant chapters of the DMRB Stage 2 report to reach a conclusion as to whether the route options would contribute to the realisation of the community objectives. The assessment also aimed to identify which of the route options would have the most impact on wellbeing outcomes.

- The process of developing the community objectives allowed the key concerns of the communities to be considered during the optioneering stage. The route options that performed more favourably against the community objectives were assessed as having the potential for positive health and wellbeing outcomes. As a result of the development of community objectives, the scope of the human health assessment was extended. The DMRB Stage 2 Human Health assessment applied a robust approach at the time of publication, both meeting and going beyond the minimum requirements of the DMRB LA 112 standard through the additional consideration of cultural heritage and associated wellbeing impacts.

The IEMA Guide to Effective Scoping of Human Health in EIA (Pyper et al., 2022b) has been published since the preparation of the DMRB Stage 2 Human Health assessment. The consideration of cultural heritage and associated wellbeing impacts as identified in the DMRB Stage 2 Human Health assessment aligns closely with the description of the wider determinant of ‘community identity, culture, resilience and influence’ from the more recent IEMA scoping guidance. Therefore, for this Stage 3 human health assessment the terminology from the IEMA guide has been used (‘community identity, culture, resilience and influence’) to describe the additional health determinant for consistency with this newer guidance, which is increasingly being regarded as the standard approach for human health assessment in EIA.

Diagram 18.2: Methodology for A9 DMRB Stage 3 Human Health Assessment

Characterise population

- Identify population groups potentially exposed to impacts of proposed scheme (i.e. neighbours, recreational groups, business owners).

- Develop a health profile of the population to take account of health and socio-economic characteristics.

- Identity vulnerable groups

within the population which may have increased susceptibility to certain health impacts.

Identify baseline health determinants

- Obtain data on quality of biophysical, social and economic environmental conditions that reflect the health determinants listed in DMRB LA 112.

- Identify assets important to community health and wellbeing. Use the community objectives to ensure this is done through a local lens.

Identify and assess potential impacts on determinants

- Identify how the proposed scheme could impact on the baseline health determinants.

- Estimate the scale (magnitude) of impact from the proposed scheme and the characteristics of the impact (i.e. whether it is permanent or temporary, widespread or localised etc.)

Identify potential health effects

- Identify associated health outcomes, based on literature review of health research.

Estimate what proportion of the community is likely to be affected. - Consider potential differences in outcomes between vulnerable groups and general population.

- Consider whether health inequalities may be widened or narrowed by impacts.

Identify mitigation and enhancement measures

- Identify measures which could reduce negative health impacts, improve health outcomes and reduce health inequalities.

Conclude assessment

- Describe key residual health outcomes associated with impacts of the proposed scheme.

- Conclude as to whether the outcomes would be positive or negative and determine the likely significance level.

- Conclude as to whether health inequalities are expected to be widened or narrowed by the impacts.

Table 18.2: Birnam to Ballinluig A9 Community Group Community Objectives

|

Community Objective Ref. |

Community Objective Description |

|

1

|

Reduce current levels of noise and pollution in the villages of Dunkeld, Birnam and Inver to protect human health and wellbeing of residents and visitors and to enable them to peacefully enjoy their properties and amenity spaces. |

|

2

|

Protect and enhance the scenic beauty and natural heritage of the area and its distinctive character and quality. |

|

3

|

Provide better, safer access on and off the A9 from both sides of the road while ensuring easy, safe movement of vehicular traffic and WCH through the villages, helping to reduce stress and anxiety and support the local community. (Non Motorised Users (NMUs) in the DMRB Stage 2 assessment are referred to as Walkers, Cyclists and Horse-riders (WCH) in accordance with DMRB LA 112) |

|

4

|

Promote long-term and sustainable economic growth within Dunkeld and Birnam and the surrounding communities. |

|

5

|

Examine and identify opportunities to enhance the levels of cycling and walking for transport and leisure, including the improvement of existing footpaths and cycle ways, to promote positive mental health and wellbeing. |

|

6

|

Ensure that all local bus, intercity bus services and train services are maintained and improved. |

|

7

|

Preserve and enhance the integrity of the unique and rich historical and cultural features of the Dunkeld, Birnam and Inver communities, thereby supporting wellbeing and the local economy. |

Community Participation and Engagement

- While this DMRB Stage 3 human health assessment has been prepared to meet the requirements of the EIA Directive, it also adopts some of the International Association of Impact Assessment’s (IAIA) best practice principles for Health Impact Assessment (Winkler et al., 2021) through the use of community participation and engagement to inform the assessment and seek opportunities for health improvement.

- At an early stage of the A9 Co-Creative Process, the Birnam to Ballinluig A9 Community Group generated a set of community objectives (as shown in Table 18.2). The A9 Co-Creative Process has influenced the human health assessment and design of the proposed scheme through early engagement. This early engagement has also helped to inform the scope and identified matters that are of importance to the community. This has allowed the community to have more control through inclusion and participation in the process. The IAIA also states that, as one of the guiding principles of HIA:

‘HIA should involve and engage stakeholders so that people potentially affected by the development initiative have an opportunity to express their hopes and concerns regarding health and can influence the formulation of public health actions’ (Winkler et al., 2021).

- This principle has been considered, and will continue to be, through the community objectives. These community objectives have identified the health priorities for the area regarding what is important to the communities in relation to their health and wellbeing.

- The community objectives identified at DMRB Stage 2 capture local community participation in the assessment process. The human health assessment has considered the community objectives as well as public consultation undertaken for DMRB Stage 3 during summer 2024 (Section 7.4, Chapter 7: Consultation and Scoping), to help inform the understanding of community priorities and views, as well as informing the judgement of significance in line with the IEMA Guide to: Determining Significance of Human Health In Environmental Impact Assessment (Pyper et al., 2022a). To date, consultation undertaken during DMRB Stage 3 has included community engagement events in August 2024, which provided the community the opportunity to feedback any further suggestions on incorporating the objectives within the design and assessment work. Engagement with three local schools was also undertaken during this time to ensure that children’s concerns are also taken into account. Relevant information gathered from this engagement has been used to inform the human health assessment reported in this chapter, and is referenced where relevant in Section 18.3 Baseline Conditions and Section 18.4 Potential Impacts and Effects.

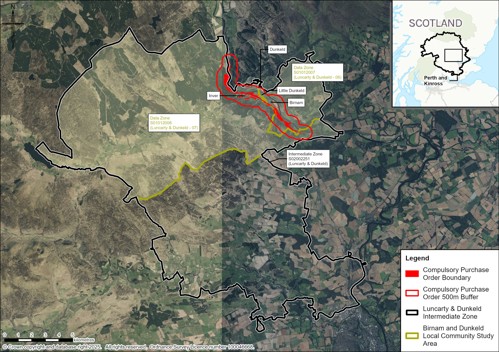

Study Areas

- The main human health study area is comprised of the 2011 data zones of S01012007 and S01012008, with a particular focus on the following communities within the study area which coincide with a 500m buffer of the proposed scheme: Birnam, Little Dunkeld, Dunkeld and Inver, which reflect the study areas applied in Chapter 16 (Population - Land Use) and Chapter 17 (Population - Accessibility). It is referred to in this chapter as the ‘Birnam and Dunkeld Community Study Area’. Data Zones are composed of Census Output Areas large enough to present statistics accurately without fear of disclosure and small enough that they can used to represent communities. The 2011 data zones were selected to ensure consistency and comparability of data. For example, the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation uses the 2011 Data Zones.

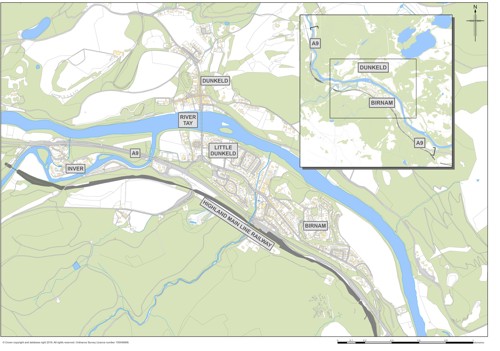

- The location of the communities are shown on Image 18.1. It was considered that there is limited potential for significant human health impacts outside the 500m population study area. However, it is recognised that there are smaller settlements – such as Dalmarnock and Dalguise – and residences in the wider area from which people may access community, education, and healthcare facilities within Dunkeld, Little Dunkeld, Birnam and Inver. The populations within these settlements and residences are considered in the assessment where relevant. For some health data, it was necessary to apply the Intermediate Zone as data were not available for areas as small as the data zones. Where the Intermediate Zone has been applied it is referred to in this chapter as the ‘Luncarty and Dunkeld Community Study Area’. Some health data are only available at regional level, in which case the Perth & Kinross Council area has been used as the study area. The study areas are indicated on Image 18.2.

Table 18.3 describes the location of the communities within 500m of the proposed scheme. The communities of Birnam, Little Dunkeld and Dunkeld each straddle two data zones, the location of the data zone relative to the community is included in the data zone column in Table 18.3.

Table 18.3: Human Health Assessment Study Area – Key Communities

|

Community |

Data Zone(s) |

Description |

|

Birnam |

S01012007 (north) S01012008 (south) |

Birnam straddles two data zones, the location of the data zone relative to the community is included in the data zone column. Community located between ch2500 and ch3450 of the proposed scheme that could be subject to potential impacts on human health. |

|

Little Dunkeld |

S01012007 (north) S01012008 (south) |

Community located between ch3450 and ch4300 of the proposed scheme that could be subject to potential impacts on human health. |

|

Dunkeld |

S01012007 (east) S01012008 (west) |

Community located approximately 500m north of the proposed scheme that could be subject to potential impacts on human health. |

|

Inver |

S01012008 |

Community located between ch4700 and ch5100 of the proposed scheme that could be subject to potential impacts on human health. |

Additionally, the EIA topics pertinent to the human health assessment each have their own study areas. These are outlined in Table 18.4. Data gathered on the study areas from these topics have been applied to the communities identified for the human health assessment where appropriate.

Table 18.4: Study Areas Defined in Technical Chapters of the EIAR

|

Chapter |

Study Area |

|

Chapter 8 (Air Quality) |

Sensitive receptors at risk of being affected by dust, including residential and other sensitive properties as well as designated sites were identified within 200m of the affected road network using Ordnance Survey (OS) Address Base Plus and Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) datasets. The extent of road links considered for the assessment of vehicle emissions from construction traffic included all roads within 500m (north and south) of the proposed scheme mainline, scoped against the DMRB LA 105 (National Highways et al., 2024) screening criteria. |

|

Chapter 9 (Cultural Heritage) |

A study area comprising the Compulsory Purchase Order Area plus an area extending 200m in all directions from it is defined. Consultation with the noise specialists identified that the extent of the study area was sufficient to identify and assess potential noise effects on the setting of cultural heritage resources. The Zone of Visual Influence (or Zone of Theoretical Visibility) was used to identify cultural heritage resources outside the study area the settings of which could be affected by the proposed scheme. Where the potential for an effect on the setting of a cultural heritage resource was identified, these cultural heritage resources were included in the cultural heritage baseline. |

|

Chapter 10 (Landscape) |

A study area extending to 5km from the proposed scheme has been adopted for the landscape assessment. Within this 5km study area, Zones of Theoretical Visibility (ZTVs) have been prepared for the existing A9 and the proposed scheme. |

|

Chapter 11 (Visual) |

A study area extending to 5km from the proposed scheme has been adopted for the visual assessment. Within this 5km study area, Zones of Theoretical Visibility (ZTVs) have been prepared for the existing A9 and the proposed scheme. |

|

Chapter 13 (Geology and Soils) |

The assessment covers a study area extending to a corridor of 250m from the compulsory purchase order boundary of the proposed scheme. For Groundwater Dependant Terrestrial Ecosystems (GWDTE), as agreed with the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA), a study area extending 100m from the existing A9 was used, and extended where required, for the purpose of dewatering impact assessments. The study area for groundwater abstractions is within 1.2km of the compulsory purchase order boundary. Typically, the minimum study area to be applied for groundwater abstraction licensing is 850 m under The Water Environment (Controlled Activities) (Scotland) Regulations 2011 and based on ‘Regulatory Method (WAT-RM-11) Abstraction from Groundwater V6’ (SEPA, 2017). However, following consultation with SEPA it was agreed the study area would be expanded to 1.2 km for abstractions (see Chapter 13 for further information). |

|

Chapter 15 (Noise and Vibration) |

A construction noise study area of 300m around the proposed scheme footprint boundary has been defined. A construction vibration study area of 100m around the proposed scheme footprint boundary has been defined. The operational noise assessment approach and methods includes an area within 600m of new road links or road links physically changed or bypassed by the project and an area within 50m of other road links with potential to experience a short-term basic noise level change of more than 1.0dB(A) as a result of the project. Operational vibration was scoped out of the assessment. |

|

Chapter 16 (Population - Land use) |

In accordance with DMRB LA 112, the initial study area for this assessment is based on the construction footprint/boundary (including temporary land-take) plus a 500m area. The guidance also states that where appropriate, the study area may be reduced or extended to support the impact assessment. In considering severance, cognisance is taken of any change in traffic volumes outwith 500m as a result of the proposed scheme. |

|

Chapter 17 (Population - Accessibility) |

The study area for the assessment of impacts on WCHs includes paths within 500m of the proposed scheme. However, the assessment was also informed by consideration of the wider area, which is particularly important in identifying potential limitations to accessing outdoor areas. The study area for the assessment of changes to views from the road was defined as the route of the existing A9 and the proposed scheme. As the proposed scheme is a dualling of the existing road, a direct comparison between the existing A9 and the proposed scheme could be made. |

|

Chapter 19 (Road Drainage and the Water Environment) |

The baseline study area for this assessment extends 500m from the footprint of the proposed scheme and includes identified water features (‘WFs’: including major to minor watercourses, drainage ditches and palaeo-channels), existing watercourse crossing points and flood inundation extents. Where appropriate, the potential for flood risk impacts associated with the proposed scheme beyond the 500m study area are considered within the assessment. |

Data Collection

- The baseline for the human health assessment has been developed through the following approaches:

- Data collection – using sources such as the Office of National Statistics (ONS), Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD), National Record of Scotland Monthly Data on Births and Deaths Registered in Scotland, 2022 Scottish Census data, National Records of Scotland, Information Services Division (IDS) Scotland website, Local Development Plans and Policy Documents, and others which are referenced where relevant.

- Spatial data mapping – using aerial photography and Ordnance Survey (OS) maps, Jacobs’ Geographical Information System (GIS) database, in addition to the above data sources.

- Consultation – with statutory and non-statutory consultees, as appropriate.

- The human health assessment presented in this chapter has drawn on data used in the DMRB Stage 2 Wellbeing Assessment which has been updated as appropriate to inform the baseline.

Consultation

- During DMRB Stage 3, consultation was undertaken with Perth & Kinross Council, the National Health Service (NHS) Scotland, Emergency Services, as well as continued consultation with the Birnam to Ballinluig A9 Community Group. The assessment has also drawn on feedback from the following consultation events:

- In-person public exhibition January 2024 presented the Preferred Route Option at Birnam Arts & Conference Centre.

- Public exhibitions August 2024, to allow members of the public to see and comment on the development of the proposed scheme design since the Preferred Route was announced.

- September 2024 that was targeted at children and young people from Royal School of Dunkeld, Pitlochry High School and Breadalbane Academy.

- Further details on consultation and scoping are provided in Chapter 7 (Consultation and Scoping). No specific responses regarding the human health assessment scope were received.

Characterising the Population

- In accordance with DMRB LA 112 (National Highways et al. 2020, p.20) a health profile for each of the communities in the study has been established through consideration of the following data where available:

- percentage of community with increased susceptibility to health issues (vulnerable members, e.g. under 16 and over 65);

- percentage of community with pre-existing health issues (e.g. respiratory disease/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD));

- deaths from respiratory diseases;

- percentage of community with long term illness or disability;

- general health;

- life expectancy; and

- income deprivation.

- Some further health data have also been on mental health indicators to reflect that health includes mental as well as physical wellbeing.

Identifying the Baseline Health Determinants

- As outlined in paragraph 18.1.3, health determinants are the range of personal, social, economic and environmental factors which can influence the health status of individuals or populations. The health determinants included in the scope of assessment are as set out in DMRB LA 112 with one addition, based on the IEMA Guide to Effective Scoping of Health in EIA (Pyper et al., 2022b). As noted above, the consideration of cultural heritage and associated wellbeing impacts was added to the scope of assessment at DMRB Stage 2 in response to the community objectives, and the DMRB Stage 2 Human Health chapter was completed before the publication of the IEMA Guide to Effective Scoping of Human Health in EIA (Pyper et al., 2022b). Therefore, after consideration of the wider health determinants, the additional cultural heritage and associated wellbeing impacts have been determined to align closely with the description of the wider determinant of ‘community identity, culture, resilience and influence’ from the IEMA scoping guidance and was added to the scope of the DMRB Stage 3 human health assessment.

- The scope of health determinants addressed in the baseline and assessment have been assigned a reference number between 1 and 10 (e.g. HD1) and are as follows:

- HD1: community, recreational and education facilities and severance/separation of communities from such facilities.

- HD2: landscape amenity and green/open space and severance/separation of communities from such facilities.

- HD3: healthcare facilities and severance/separation of communities from such facilities;

- HD4: community identity, culture, resilience and influence;

- HD5: spatial characteristics of the transport network and usage in the area, including the surrounding road network, Public Rights of Way (including bridleways), cycle ways, non-designated public routes and public transport routes;

- HD6: air quality;

- HD7: noise and the ambient noise environment;

- HD8: sources and pathways of potential pollution;

- HD9: safety associated with the existing affected road network; and

- HD10: flood risk.

- Where appropriate, baseline information on health determinants has been obtained with cross-references to other assessments in the EIA, for example, the air quality and noise assessments.

Identifying and Assess Potential Impacts on Determinants

- The first step in the identification of impacts was to understand how the baseline health determinants would be likely to be affected by the proposed scheme. A change to a single health determinant can affect the health status of different individuals or communities depending on their characteristics and sensitivity to change, thereby generating multiple health outcomes. Again, for health determinants covered by other topics of this EIA, reference has been made to the relevant topic chapters to identify the nature and scale of impacts on the health determinants.

- The methodology, as set out in DMRB LA 112 and the IEMA guidance, involved the assessment of changes in health determinants and relating these to potential population health impacts through consideration of the local community health profiles and scientific evidence.

Identifying Potential Health Effects

- In order for there to be a potential likely health effect, a health pathway must be established that ‘shows a plausible theoretical link between source-pathway-receptor; and the occurrence of which is judged as probable’ (IEMA, 2022b). As recommended by IAIA’s Human Health: Ensuring a High Level of Protection (IAIA, 2020), a literature review has been undertaken to determine an association between changes that are likely to occur due to the proposed scheme in relation to the health determinants, and the resulting potential changes to health outcomes. The results of the literature review are provided in paragraphs 18.2.27 – 18.2.61.

- Identification of a health pathway does not mean that there would be a significant impact on human health. Professional judgement has been applied using the IEMA assessment criteria (IEMA, 2022a) to determine the level of significance (See ‘Assessment Reporting and Significance Criteria’ below).

- Evidence derived from a literature review for health outcomes, and the interpretation of this evidence for the health determinants considered within this assessment, are summarised below.

Human Health Evidence Associated with Community, Recreational and Education Facilities (HD1), Landscape Amenity, Green/Open Space (HD2), and Healthcare Facilities and Severance/Separation of Communities from Such Facilities (HD3)

- The DMRB LA 112 defines ‘severance’ as ‘the extent to which members of communities are able (or not able) to move around their community and access services/facilities’. However, within transport and health literature, community severance may be applied to any one of, or a combination of, the following impacts: reduction in pedestrian access due to high traffic flows; barrier effect of physical infrastructure; changes in mobility and accessibility; reductions in social contacts; and psychological separation of neighbourhoods. The various definitions of community severance make comparisons of research difficult (Mindell and Karlsen, 2012). There are various recent studies which provide evidence that traffic speed and volume reduces levels of physical activity, social contacts, children’s play and access to goods and services. Anciaes et al. (2016) identify that:

- high levels and speeds of motorised traffic discourage walking; and

- high levels and speeds of motorised traffic limit social contact between residents living on the opposite sides of roads.

- However, the research into associations between community severance and mental or physical health outcomes is limited. Mindell and Karlsen (2012) undertook a systematic review on community severance and health. They identify that Appleyard and Lintell’s study of San Francisco showed a reduction in social contacts due to increased traffic, and that there is research which shows an inverse association between social contacts and mortality risk. However, they could not identify any studies of mortality or morbidity which have examined reductions in social contacts as a result of new roads, increased traffic volumes or traffic speeds. They conclude that:

‘The chain of inference for the health effects of community severance does not currently extend to direct observation. It seems inherently likely that the effects of community severance do indeed impact on health, with adverse health consequences of reduced social contacts also occurring when this social disruption is due to road traffic. Given the scale of the effect on mortality of high social integration, which is of similar magnitude to stopping smoking (Holt-Lundstad et al., 2010) it is of great public health importance that research is conducted to confirm the postulated links and to establish which are the important components of community severance for health and how they can be ameliorated.’ (Mindell and Karlsen, 2012).

- The ability to access shops, recreational facilities and education helps to support the health and wellbeing of communities. Severance to core/local paths, transport networks, open space and community, recreational, educational and healthcare facilities has the potential to impede access and exacerbate health inequalities. This can result in reduced social cohesion and physical activity and have negative impacts on mental health (Mindell and Karlsen, 2012; Marmot et al., 2020).

- The intrinsic qualities of green and blue spaces have been shown to enhance health and wellbeing through connection with nature and cognitive and psychological restoration, the opportunity to perform physical activity through active travel, and enhance social interaction (Gascon et al., 2015; Bray et al., 2022). Coventry et al. (2021) conducted a systematic review on nature-based outdoor activities for mental health in community-based settings which shows that nature-based interventions can effectively improve mental health and wellbeing and that improvements in mental health might be attributed to nature connectedness, social support, physical activity and purposeful behaviour.

- While the formal healthcare services account for only 20% of population health (the other 80% being related to wider determinants of health such as the health behaviours and social, economic and environmental conditions in which people live) (American Hospital Association, 2020), access to healthcare is nevertheless important for individuals and a fundamental human right. Survival rates from out-of-hospital cardiac arrests (Lyon et al., 2004) and stroke (Simonsen et al., 2014) are strongly influenced by emergency response times. Therefore, any delay to emergency admissions caused by traffic disruption could have a significant impact on health outcomes for some individuals who need emergency care.

Interpretation for Assessment

- Large increases in traffic volume or speed, or creation of physical infrastructure which may act as a barrier to pedestrian movement or use of outdoor space for social interaction, has been considered as negative for health, while large reductions in traffic volume or speed, or removal of physical infrastructure which support improved pedestrian movement or use of outdoor space for social interaction, has been considered as positive for health. Given the lack of research on size of effect, or thresholds at which severance may occur, significant effects on health outcomes are judged likely only if changes would be widespread across the human health study area.

- Disruption of access to healthcare facilities (whether by vehicle or on foot) have been considered negative for health. The significance has been judged in relation to the sensitivity of the population, the nature of the health services (i.e. whether emergency care or not) and the scale of impact on access.

Human Health Evidence Associated with Community Identity, Culture, Resilience and Influence (HD4)

- Communities with high levels of social capital (indicated by sets of shared values in a community, participation and working together) have advantages for the mental health of individuals, and these characteristics have also been seen as indicators of the mental well-being or resilience of a community (Cooke et al., 2011).

- Creative activities improve self-esteem, confidence, motivation, happiness and reduce stress and enhance control. Leisure and physical activity enhance well-being by increasing feelings of competency and relaxation, distracting from difficulties, as well as enhancing social inclusiveness and support (Caldwell, 2005). Research has shown that the use of artistic media in health care and in communities can have a variety of benefits for health outcomes. Participation in arts enhances well-being though direct engagement in art activity, although this facilitates social participation which also enhances well-being (Fancourt and Finn, 2019). A systematic overview conducted by Leigh-Hunt et al. (2017) highlights that there is consistent evidence linking social isolation and loneliness to worse cardiovascular and mental health outcomes.

Interpretation for Assessment

- Based on the evidence, the assessment has considered how the proposed scheme may affect the places and activities that local people associate with a sense of their community identity. These aspects will be considered as important for social wellbeing.

Human Health Evidence Associated with Spatial Characteristics of the Transport Network and Usage (HD5)

- A good transport system is essential for a healthy society. The impact of air pollution on health is well-known, but transport affects the health of people across society in multiple ways. Investing in transport is seen as a way to address widening health inequalities and regional disparities in public health. The quality of the transport infrastructure and the adequacy of transport services directly affect health by, for example, enabling active modes of travel (such as walking and cycling) or reducing road accidents and harmful emissions. Wider, indirect impacts on health include enabling people to get to work, school, hospital and fresh food shops, as well as social events and leisure activities – aspects of life that are important for good physical and mental health (as evidenced above). Transport infrastructure and provision can have direct and indirect effects on mental and physical health by supporting access places of employment and study, community and recreational facilities or public transport access points for pedestrians and cyclists.

- The health benefits of regular physical activity are well researched and widely accepted. For most people, the easiest forms of physical activity are those that can be built into daily life, for example, by using walking or cycling as an alternative to motorised transport for everyday journeys such as commuting to work or school. Active forms of travel, such as walking and cycling, are associated with a range of health benefits, including improved mental health, reduced risk of premature death and prevention of chronic diseases such as coronary heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis, depression, dementia and cancer (British Medical Association, 2012). Research also suggests that countries with the highest levels of active travel generally are amongst those with the lowest obesity rates (Bassett et al., 2008).

Interpretation for Assessment

- For the health assessment, increases in transport choices and opportunities for active travel have been considered positive for health on account of health benefits associated with reliable transport and physical exercise, as well as benefits in terms of reducing pollution and other negative aspects of motor vehicles. However, significant impacts on population health outcomes are only predicted where a substantial modal shift to active modes of travel are anticipated.

Human Health Evidence Associated with Air quality (HD6)

- Poor air quality can result in human health conditions such as respiratory problems, cardiovascular disease and lung cancer (Royal College of Physicians, 2016).

- A systematic review conducted by Chen and Hoek (2020) has considered the health effects of air pollution based on health effects from long-term exposure to Particulate Matter (PM). This review provided clear evidence that both PM5 and PM10 were associated with increased mortality from all-causes (natural-cause mortality or non-accidental mortality from all-causes, except external causes such as accidents, suicide and homicide), cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease and lung cancer. A systematic review conducted by Orellano et al. (2020) also found that an increase in outdoor concentrations of PM10, PM2.5, nitrogen dioxide and ozone increases the risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality in humans.

- A systematic review conducted by Wang et al. (2021) considered the link between short-term exposure to nitrogen dioxide and mortality and identified evidence of association between short-term exposure to nitrogen dioxide and all-cause, cardiovascular and respiratory mortality.

- Based on the scientific evidence from systematic reviews, the WHO Air Quality Guidelines (2021) provide global guidance on threshold and limits for key air pollutants that pose health risks. These guidelines are much more conservative than the current UK Air Quality Objectives (AQO).

- Direct impacts on air quality have been reported in Chapter 8 (Air Quality). As reported in Chapter 8, human exposure to particulate matter (both in the sort and long term) and nitrogen oxides can have adverse health impacts. There is no proven safe threshold at which human health is not at risk from particulate matter.

Interpretation for Assessment

- There is good evidence that transport related air pollutants such as PM10, PM5 and NO2 are associated with an increased risk of a range of health outcomes, including at levels of pollution substantially below the AQO. However, it should be noted that the evidence from the systematic reviews, which underpin the WHO Air Quality Guidelines, are based on relatively small sample sizes and the WHO Air Quality Guidelines are designed to protect large populations from small increases in disease and mortality. For most individuals, the increase in risk posed by outdoor air pollution is extremely low compared to other risk factors, such as diet, smoking and level of exercise.

- It should also be noted that while road traffic contributes to pollution, it is one contributor among many other sources, and in the case of PM, sources such as residential, commercial and public sector combustion (which would include woodburning stoves, bonfires etc.) provide a greater share of the PM emissions.

- Any increase in exposure to air pollution is negative for population health, while any decrease in exposure to air pollution is positive for population health. However, significant impacts on population health (i.e. where a notable change in the level of health outcomes) are only judged likely where the proposed scheme would cause an exceedance of the AQO or where a substantial change in concentrations of pollutants are anticipated compared to the baseline (Do-Minimum). The assessment has also been informed by Chapter 8 (Air Quality).

Human Health Evidence Associated with Noise and the Ambient Noise Environment (HD7)

- High levels of noise nuisance and vibration cause by traffic and construction activities can cause psychological distress (Clark et al., 2020) and there is evidence to suggest increased noise exposure can increase the risk for Ischemic Heart Disease (IHD) and hypertension (Rompel et al., 2021). There is also increased risk of sleep disturbance, hearing impairment, tinnitus and cognitive impairment, with increasing evidence for other health impacts, such as adverse birth outcomes and mental health problems (WHO, 2024). Noise from road traffic alone is the second most harmful environmental stressor in Europe, behind only air pollution from fine particulate matter (WHO, 2018). The harmful effects of noise arise mainly from the stress reaction it causes in the human body, which can also occur during sleep. The Environmental Noise Guidelines for Europe (WHO, 2018) set out recommendations for road traffic noise and other sources of environmental noise, following a series of systematic reviews of the current evidence on the following critical health outcomes: annoyance, sleep disturbance, cardiovascular disease, and cognitive impairment.

Interpretation for Assessment

- Increases in noise levels are considered negative for health, while decreases are considered positive. It is noted that the WHO has considered the evidence sufficient to support a strong recommendation that road traffic noise should be reduced to below 53 dB Lden. This guideline level is benchmarked at the level where 10% of a population are likely to be ‘highly annoyed’. Noise of this level is relatively widespread in the UK, particularly in urban areas. Annoyance is regarded as a relatively mild health effect, as indicated by the disability weighting applied by the WHO.

- The more serious health outcome for which evidence is of a high quality is IHD. This risk is linked to long-term exposure to higher levels of noise. However, it should be noted that the risk of IHD linked to noise is very small compared to other risk factors. Nevertheless, it is a public health issue of concern due to the widespread exposure of populations to traffic noise.

- The assessment has also been informed by Chapter 15 (Noise and Vibration). Health effects have been judged to be significant if the proposed scheme is expected to effect a large change in the noise environment.

Human Health Evidence Associated with Sources and Pathways of Potential Pollution (HD8)

- Air pollution and noise are the main pollutants associated with road transport, as described above. In the context of a road scheme, key sources of pollution would be fuels, oils, cementitious material and other substances used during construction and operation, and the presence of any historical contamination in the ground at the construction site.

- Pathways to exposure could include emissions to air and spillages to water or soil, and disturbance of historical contaminants in the ground via excavations during construction. People have the potential to be exposed to pollutants through pathways such as ingestion, inhalation and dermal contact with soils, soil dust, and shallow groundwater and surface water, or by migration of ground gases into confined spaces. While people are exposed to various chemicals routinely in life, there are some hazardous chemicals that raise particular health concerns because of their widespread presence in the environment, their toxicity, and their capacity to magnify and accumulate in the environment and in people. The fact that they are widespread and many people come into contact with them also means that they have the potential to harm the health of large populations. Chemicals, or groups of chemicals, of major public health concern include air pollution, arsenic, asbestos, benzene, cadmium, dioxin and dioxin-like substances, inadequate or excess fluoride, lead, mercury and highly hazardous pesticides (WHO, 2020).

Interpretation for Assessment

- The assessment has been informed by Chapter 13 (Geology and Soils) and Chapter 19 (Road Drainage and the Water Environment) but has also considered the likelihood of human exposure to pollution after taking account of legislative frameworks, such as that afforded by the Environmental Protection Act 1990, Health & Safety legislation and standard environmental management practices. While exposure to pollution has been assumed as negative to health, effects have only been considered to be significant if widespread population exposure is considered likely or particularly vulnerable groups are affected.

Human Health Evidence Associated with Safety Associated with the Affected Road Network (HD9)

- Road traffic collisions are a direct cause of mortality, injuries and disability. Road traffic collisions also have a severe effect on mental health and are the leading cause of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the general population (Kovacevic et al., 2020) with life-long health implications for individuals affected. The WHO predicts that road traffic collisions will become the fifth leading cause of death globally by 2030 (WHO, 2023b) and that they are currently the leading cause of death for children and young adults (aged 5-29 years) (WHO, no date).

- Changes to traffic movements and flows can also change people’s perceptions in relation to traffic safety, which can act as a barrier to travel, physical activity and social interaction (Anciaes et al., 2017). Commentary on road traffic accidents is provided in Chapter 2 (Need for the Scheme).

Interpretation for Assessment

- While the greater proportion of road collision fatalities are among car drivers, the fatality rate among motorcyclists, pedestrians and cyclists is substantially higher, indicating the greater vulnerability for these types of travellers. In most cases, fatalities among these types of travellers involve a collision with a car or other motor vehicles. Measures which help separate vulnerable travellers from motor vehicles have been assumed to be positive for health.

- The results of traffic collision analysis have informed the assessment. Significant positive health outcomes are judged to be likely if there is a substantial reduction in risk of serious injury and fatalities from collisions, particularly for motorcyclists, pedestrians and cyclists, whilst accessibility for these modes of travel is maintained or improved.

Human Health Evidence Associated with Flood risk (HD10)

- Flooding can result in injury and illness, and in extreme cases, death by drowning. Flooding can impact people’s wellbeing, psychosocial resilience, relationships and mental health, often over extended periods of time (Stanke et al., 2012; Public Health England, 2020).

- Direct impacts on flood storage and flow mechanisms have been reported in Chapter 19 (Road Drainage and the Water Environment).

Interpretation for Assessment

- As part of Scottish Planning Policy, any new development must remain flood free during any design flood event as well as not increasing flood risk in the surrounding areas. The human health assessment has considered whether flood risk would be improved and/or the likelihood of the proposed scheme in changing people’s perception of flood risk.

Assessment Reporting and Significance Criteria

- The DMRB LA 112 requires health outcomes to be reported according to the categories in Table 18.5.

Table 18.5: Human Health Outcome Categories – DMRB LA 112

|

Health Outcome Category |

Health Outcome Description |

|

Positive |

A beneficial health impact is identified |

|

Neutral |

No discernible health impact is identified |

|

Negative |

An adverse health impact is identified |

|

Uncertain |

Where uncertainty exists as to the overall impact |

- The assessment criteria for human health outcome categories in relation to sensitivity, magnitude and significance are outlined in paragraphs 18.2.64 – 18.2.71.

Assessment Criteria

Sensitivity Criteria

- The DMRB LA 112 states that ‘once the health profile of communities has been established, the sensitivity of a community/population to change shall be identified (supported with evidence).’ It goes on to state that the sensitivity shall be reported as low, medium or high. However, the DMRB LA 112 does not provide sensitivity criteria on which to base this judgement on. Therefore, sensitivity criteria from the IEMA guidance on determining significance for human health in Environmental Impact Assessment (Pyper et al., 2022a) have been used to guide the assessment. The criteria in the IEMA guidance use four categories of sensitivity (high to very low). Therefore, the criteria have been adapted to combine the very low and low sensitivity criteria into one. This allows for alignment with the DMRB LA 112 reporting requirement for sensitivity. The criteria used are set out in Table 18.6.

- Depending on the impact being assessed, some population groups may be more vulnerable to impacts than others. For example, young people and elderly people are considered more sensitive to poor air quality (Royal College of Physicians, 2018). Similarly, people in residential premises, schools, and places of worship are likely to be more sensitive to some impacts e.g. noise. For this assessment, vulnerable groups have been considered on a case-by-case basis.

Table 18.6: Criteria for Sensitivity of Population Groups (adapted from Pyper et al., 2022a)

|

Sensitivity level |

Indicative criteria for the population |

|

High |

High levels of deprivation (including pockets of deprivation);

|

|

Medium |

|

|

Low |

|

Magnitude Criteria

- For the assessment of human health, magnitude has been determined based on the potential for a change in health determinant and, where there is a pathway for this change in a health determinant to lead to a change to health status for a group or population, known as a health outcome. In the absence of criteria for determining magnitude in DMRB LA 112, this has been determined using the IEMA guidance (Pyper et al., 2022a) and professional judgement based on data gathered and the conclusions of the other chapters e.g. air quality. Table 18.7 provides the magnitude criteria included in the IEMA guidance.

Table 18.7: Criteria for Magnitude of Health Impacts (source: Pyper et al., 2022a)

|

Magnitude level |

Indicative criteria for the magnitude of change for health determinants on the population groups |

|

High |

|

|

Medium |

|

|

Low |

|

|

Negligible |

|

- Neither the DMRB guidance (LA 104 or LA 112) nor the IEMA guidance provide definitions for long-term, medium-term or short-term. The following timescales, applied in this assessment, have been defined using professional judgement and experience from similar projects:

- long-term: impacts lasting approximately ten years or more;

- medium-term: impacts which would last approximately three to ten years;

- short-term: impacts which would last approximately six months to three years;

- very short-term: impacts which would last up to six months; and

- transient: impacts lasting a matter of hours or up to a weekend.

Significance Criteria

- The judgement of significance involves the synthesis of information to determine whether health effects are important, desirable and/or acceptable in terms of public health. This assessment has been guided by the significance criteria from the IEMA Guide to Determining Significance for Human Health in Environmental Impact Assessment (Pyper et al., 2022a) as set out in Table 18.8. Similar to DMRB LA 104, the process for determining the significance of effect, as set out in the IEMA Guide to Determining Significance for Human Health in Environmental Impact Assessment (Pyper et al., 2022a), takes into consideration the sensitivity of the population and the magnitude of change.

- The matrix presented in Table 18.9 is based on the generic indicative EIA significance matrix provided in the IEMA guidance but has been adapted through the removal of the ‘very low’ sensitivity category, to align with the DMRB LA 112 sensitivity reporting requirement (as explained in paragraph 18.2.64 above). A matrix based on the IEMA guidance has been used in preference to the generic matrix provided in Table 3.8.1 of DMRB LA 104 for the following reasons:

- Table 3.8.1 of DMRB LA 104 differs from DMRB LA 112 in providing for five categories of sensitivity rather than three, meaning a greater modification of the matrix is needed to align with DMRB LA 112.

- DMRB LA 104 allows for the reporting of ‘neutral’ significance for negligible or minor magnitude impacts, which is not appropriate for some health determinants where there is no level below which an effect on a population can be observed, such as is the case of air pollution. Therefore, the IEMA guidance which applies the term ‘negligible’ has been adopted for this human health assessment. The term ‘neutral’ is only applied in this assessment where no change to a determinant is predicted.

- Similar to Table 3.8.1 in DMRB LA 104, where two significance categories are provided for a cell in Table 18.9, evidence has been provided to support the reporting of a single significance category.

Table 18.8: Criteria for Significance of Effect

|

Level |

Indicative criteria for the significance of effect |

|

Major (significant) |

|

|

Moderate (significant) |

|

|

Minor |

|

|

Negligible |

|

Table 18.9: Indicative Health Assessment Significance Matrix

|

Magnitude Sensitivity |

No change |

Negligible |

Low |

Medium |

High |

|

High |

Neutral |

Minor or negligible |

Moderate or Minor |

Major or Moderate |

Major |

|

Medium |

Neutral |

Minor or negligible |

Minor |

Moderate |

Major or Moderate |

|

Low |

Neutral |

Negligible |

Minor or Negligible |

Minor |

Moderate or Minor |

- Note that the initial assessment of potential impacts does not consider additional mitigation, only embedded mitigation as part of the design. The assessment of residual effects does consider additional mitigation and outlines the anticipated effects after all mitigation is taken into account.

Mitigation

- The approach to mitigation follows the hierarchical approach of avoidance and prevention, reduction, and remediation as set out in Table 3.5 of Chapter 3 (Overview of Assessment Process).

- DMRB LA 104 (Highways et al., 2020a, p.18) requires mitigation to be reported under two distinct categories:

‘1) embedded mitigation: project design principles adopted to avoid or prevent adverse environmental effects; and

2) essential mitigation: measures required to reduce and if possible offset likely significant adverse environmental effects, in support of the reported significance of effects in the environmental assessment.’

- The embedded mitigation measures outlined in Table 6.2 of Chapter 6 (The Proposed Scheme) and in each of the relevant topic chapters e.g. noise and vibration, have been taken into account prior to the human health impact assessment.

- Where negative impacts are predicted, or where opportunities to maximise health benefits are identified, recommendations for mitigation or enhancement have been put forward with further consideration of the community objectives. This will help to challenge the design against its ability to meet community objectives, with an assumption that this will help improve community wellbeing outcomes. Additional mitigation for human health impacts is considered as essential mitigation and is set out in Section 18.5.

Cumulative Effects

- Potential for cumulative effects of the proposed scheme, and those of the proposed scheme in combination with other reasonably foreseeable developments, are assessed in Chapter 21 (Assessment of Cumulative Effects).

Limitations to Assessment

- At the time of writing, the construction information available, including information relating to haul routes within temporary works areas and construction vehicle traffic, is indicative only and subject to change once the Contractor is appointed. Therefore, any impacts on health assessed in relation to construction traffic may be subject to a similar change.

- As noted in Chapter 1 (Introduction), the design of the proposed scheme may be refined, but will still be deemed to comply with this EIAR provided that such refinements to this design would be subject to environmental review to ensure that design refinements do not introduce new significant effects not reported in this EIAR or change the significance of effect reported in this EIAR from non-significant to significant.

- The health profile created for the communities has largely been based on data collection from secondary sources. Whilst this search has provided general information on vulnerable groups along the proposed scheme, the data gathered is high-level and not all specific cases have been captured. In particular, the assessment does not assess the health outcomes for individuals.