Site Visit Feedback

Introduction to Video Study Findings

The site visits were conducted using the methodology described in Section 2 of this report. Each of the participants gave a verbal commentary at each of the site locations and this section contains a summary of the most prevalent and prominent themes determined from the site visits carried out for this phase of the research. Five of the participants from the online interviews were available to undertake the on-site phase of the works. The numbering system used to identify the participants, as seen in Table 3‑1, has continued to be used for this element of the study.

Participant 2

Participant 2 had no vision and was a younger person requiring the use of a cane; they also have some hearing impairments. However, assisted hearing with hearing aids were adequate for close speech. This section gives a summary of the key themes the participant highlighted during their site visits at the sites discussed in Section 2.6.

Crossings

During the site visit at Constitution Street, Participant 2 was able to identify the kerb with the use of their cane and noted they would be comfortable to traverse this kerb and crossing the road with the use of their cane.

They were also able to identify the newly installed tram track while crossing the carriageway. The participant was able to detect the crossing point and the Pedestrian Demand Unit (PDU) from the footway with the use of the tactile paving, as shown in Figure 4‑1.

The participant reported relying on people to guide or help on occasions when crossing cycleways. During the site visit at Picardy Place, they noted that it was impossible to tell when they were approaching the cycleway from the footway, see Figure 4‑2. They reported that the tactile paving was not providing any detectable difference to the participant using the cane at that location.

From observation and listening to the feedback from the participant the level of conspicuousness of tactile paving and kerbs can be considered to be a key factor in their ability to complete the safe use of these areas.

Participant 4

Participant 4 has hearing impairments; however assisted hearing through the use of hearing aids is adequate for close speech. They also have some balance issues. This section gives a summary of the key themes the participant highlighted during their site visits at the sites discussed in Section 2.6.

Longitudinal Kerbs

A recurring issue raised by this participant was the height of the kerb from the footways to the roadway and cycleways. The participant considered that the height of the kerb was not distinct along the newly constructed cycleway between the footway and the segregation island. However, this was a subjective impression based on the lived experience of multiple functional impairments.

The participant made observations regarding kerb height during the site visit to George Street. It was evident that the conspicuous double kerbs of varying height were present at the disabled on-street parking markings as shown in Figure 4‑3. This area is understood to be constructed pre-2010 and the Designing Streets policy. Other participants observed that these older disabled parking areas were too narrow for safe use as a wheelchair was forced to approach from the roadside where little separation from traffic was available. This was considered hazardous for disabled users. However, it was noted the kerbs present at the bus stop at this site were good for pedestrians and wheelchairs.

This participant did not have issues with the kerbs due to their functional impairments, however, they made valuable observations based on their lived experience and using their local knowledge. Their lived experience with non-inclusive design with regard to their own impairments had given them insight to the needs of other functionally impaired users.

Crossings

Another issue raised by this participant was the inconsistencies in road markings during the site visit at Picardy Place. It was demonstrated that the cycleway crossed the carriageway with some inconsistencies in the road markings. For instance, the painted cycle picture is only in one part of the cycleway junction, as shown in Figure 4‑4. They noted these inconsistencies were present where the cycleways are connecting with the carriageway and that the intended directionality was unclear, presenting a substantial hazard of collision with vehicle traffic and other cyclists. It was also observed that footway obstructions by cycle parking facilities were potentially hazardous on small buffer areas between the carriageway and cycleway, as shown in Figure 4‑4.

Although these observations represent the lived experience of the participant due to their multiple functional issues, the observations also relate to the issues faced by other users. Observations in this site were subject to temporary road works and this was taken into account when considering the live (usable areas).

Surface Type Contrast

Some observations were made regarding the road surface colour during the site visit at Picardy Place. The contrast in colour between the footway, carriageway and tram surfaces was described as good by the participant. In addition, the kerb stones developed increased contrast in colour when wet but the contrast was also reduced where the wet surface darkened. Similarly, the participant noted the contrast in the colour of the footway and the cycleways as shown in Figure 4‑5.

Again, this participant was referring to their lived experience and the observation about the contrast is useful as it relates to all users.

Participant 5

Participant 5 had very low physical movement and required the use of a wheelchair, representing the approximate mean level of capability in this group, and occasionally requiring assistance. This section gives a summary of the key themes the participant highlighted during their site visits at the sites discussed in Section 2.6.

Controlled Crossings

During the site visit at Constitution Street using the temporary controlled crossing at the signalised junction, Participant 5 noted that the kerb height and the sloping towards the carriageway between the road and the footway at the traffic junction, as shown in Figure 4‑6: Constitution Street controlled crossing point could cause the wheelchair to tip over if there was a stabiliser on the wheelchair.

From observation and listening to the feedback from the participant a key problem for wheelchair users as it relates to the kerbing arrangements is the drop height more than the shape. Figure 4‑6 also clearly shows the difficulty in assessing the kerb height on the other side of the road. These could be measured as this is the determining factor on whether they will be able to traverse them without tipping over.

Cycleway Crossings

This participant was not comfortable with crossing the cycleway during the site visit at Picardy Place. It was evident that they were unable to hear approaching cyclists and considered them a significant hazard while crossing the cycleway, as shown in Figure 4‑7 by a passing electric cyclist.

From observation and direct feedback from the participant there was clearly a strong perception of the risk of collision from cyclists and the perception that the outcome of any collision has the potential to be more serious for mobility impaired users who often experience fragility, as discussed in Section 3.3.3.

As it relates to kerbs it has be seen that the chamfered arrangement can allow mobility impaired users to enter down onto the cycleway. But depending on momentum, wheel type, and user it can result in difficulties getting up and out. This is particularly true if there is psychological pressure due to the presence or perception of cyclists approaching.

Notable Kerb and Road Arrangements

During the site visits at all locations Participant 5 expressed difficulty ascending and descending from various kerbs. Specifically at George Street where there was on-street parking that they considered to be untraversable.

Some kerbs on the non-managed area of the Constitution Street site were considered to be hazardous by the participant. For example, a cobbled footway section for a private access caused painful vibration of the wheelchair and was difficult to traverse as shown in Figure 4‑8.

Another noticeable issue with regards to cobbled surfaces was observed at the George Street site where the car parking areas in the middle of the road are cobbled. The participant noted that the cobbles separating the roads are difficult to traverse as they caused the wheelchairs to wobble (pitch and lateral acceleration). Similarly, the participant noted that uneven cracked footways were hazardous to wheelchair users, which was a theme that was frequently recorded from statements of other participants in the overall study.

Furthermore, the interactions between pedestrians and people in wheelchairs was seen as problematic on the footway, particularly where street furniture and restaurant seating used footway space as pedestrian and other footway traffic was mixed.

Participant 7

Participant 7 had low visual capability that required the assistance of a guide dog. The dog with him at the site visit was a relatively recent (6 months) and he considered it to be “still learning”. They also had hearing impairments; however, their hearing through the use of hearing aids was adequate for close speech, although they used subtitles when watching TV. This section gives a summary of the key themes the participant highlighted during their site visits at the sites discussed in Section 2.6.

Longitudinal Kerbing

During the site visit at Picardy Place the participant noted that they could recognise the kerbs adjacent to the cycleway and felt that the kerb was useful and beneficial for the crossing of the cycleway as it provided a physical boundary that could be felt between the provisions.

However, there was a part of the route where they could not detect the boundary between the footway and the cycleway, which resulted in them moving into the cycleway by accident, which could have resulted in a collision. This happened at the location where the kerbs along the footway flattened out to the level of the cycleway with no tactile paving present to indicate a change.

They also reported that it is difficult to know if any cyclists were approaching them as they were unable to hear them approaching.

Another noticeable and potentially problematic issue identified at the same site was that the footways in the area were graded in such a way that at crossings the footway and cycleway would be at the same level, in a raised table format, as shown in Figure 4‑9. The participant noted that this was not their preferred crossing arrangement, and they considered it to be problematic; regardless of whether tactile paving was provided on both sides of the crossing.

From the online interviews it was noted that the raised table format of crossing was not the preferred type of arrangement for many types of impaired user due to the previously discussed risks. The participant did not find the tactile paving helpful in this case onsite because it is entirely at the same grade and level as the cycleway and does not provide them any directional information or feedback that would allow them to safely utilise it. They highlighted that they felt that it was purely designed for cyclists and had not considered the needs of road users such as themselves.

The participant noted that the kerb height separating the road and the cycleway was acceptable, in general, except for the previously described raised table arrangement crossing.

Road Crossings with Guide Dog

An important issue noted at all the site visit locations was when the guide dog, that was suitably trained, found it difficult to walk straight across the road several times during the visit. As shown in Figure 4‑10, the guide dog frequently adopted a diagonal route across the road, potentially due to its perception of hazards. George Street contained a central area used for parking, and this may have been an unfamiliar arrangement to the guide dog. However, this is not unusual in Edinburgh.

Furthermore, in addition to the inability of the guide dog to walk directly across during informal crossings, the guide dog was also evidently confused and unable to guide the participant to the push button unit at the crossing point as shown in Figure 4‑11. This was potentially due to the presence of temporary signage but the dog also did not appear to detect the tactile paving.

There is potential that these arrangements are causing confusion to the participants and their guide dogs. This makes them less confident in travelling along the routes and undertaking informal crossings. This can be further compounded by inconsistent kerbing arrangements that may not fully meet the needs of functionally impaired users.

Cycleway Crossings with Guide Dog

The guide dog tended to walk around pedestrians and cyclists. Specifically, the participant noted that his guide dog would usually not stop for the cyclists but would walk around them as shown in Figure 4‑12. It should be noted that the cyclists did not stop and often did not slow. The guide dog crossed toward the cyclist and had to take evasive action to avoid a collision as the cyclist passed.

Closely related to the interaction of the guide dog, pedestrians and cyclists, the guide dog was further confused walking toward a parked Taxi as shown in Figure 4‑13. This may be potentially be due to the parking area not being clearly defined as separated from the carriageway.

It was, however, also possible that the guide dog was confused about the intention of the visually impaired participant. The participant described how he had developed micro signals to the guide dog over time, conveyed with hand and finger movements, but was unclear regarding the nature of these signals. He reported that the dog; that was relatively new to them, was “still learning” these and therefore considered that the results could be variable.

As can be seen in the figures above these interactions often happened in areas where there is a lower profile chamfered kerb to distinguish the separation between the pedestrian footway and the cycleway.

From observation and interpretation of the feedback from the participant it was possible that the guide dog and participant did not find these kerbs sufficient to assist in the differentiation between the routes. This confusion could lead to functionally impaired users becoming confused and travelling into opposing traffic streams.

Participant 8

Participant 8 has very low physical movement with no movement of the legs (Paraplegia) and required the use of a wheelchair with occasional need for assistance. However, they were physically able to manoeuvre their wheelchair and confident in their ability to do so. This section gives a summary of the key themes the participant highlighted during their site visits the sites discussed in Section 2.6.

Crossing Signalised Junctions

This wheelchair user noted that the push button unit at the temporary signalised junction used during the site visit on Constitution Street was too high for them to use comfortably at wheelchair height, as can be seen in Figure 4‑14. As can be seen in the picture the push button unit on the permanent crossing that was newly installed but not yet in use at the time of the interview was at approximately the same height.

There was also a possibility of the wheelchair rolling forward into the road traffic as there was a gradient leading to the kerb edge shown in Figure 4‑15. The proximal kerb was flush with the roadway and the farthest was within capability. It was noted that the tactile paving could not stop the wheelchair from rolling down and that both arms were required for stable braking.

The observations raised by this participant when considered in the context of this study is that there are a lot of factors working against the impaired user as they attempt to cross at these controlled crossings. It should be remembered that they are subject to timed signal changes and have to be traversed with other pedestrians. As such standardised arrangements would help as it would give them less to consider and assess as they make their attempt to cross safely.

Uncontrolled Crossings

The participant demonstrated the difficulty of crossing the road where there was no controlled crossing on Constitution Street, as shown in Figure 4‑16. They noted that the front wheels of the wheelchair were smaller than the kerb which meant they couldn’t roll over the kerb. They demonstrated the physical manoeuvre which involved to traverse the kerb by rolling back on the two large wheels, lifting the two front wheels off the ground and onto the kerb top, and then pushing off with the two large wheels. It was noted by the participant that the kerb heights were higher where there was on-street parking.

As a confident and highly able wheelchair user they reported being happy with this manoeuvre and height of the kerb. However, it was noted that the kerb was likely to be hazardous for many wheelchair users that were perhaps less experienced, less confident, or less physically able in their manoeuvring.

With respect to the kerbs bordering the cycleway at Picardy Place, the participant noted that they would attempt the kerbs along the cycleway without a crossing. This was demonstrated during the site visit by negotiating the kerbs with the wheelchair. It was raised by the participant that the kerb, shown in Figure 4‑17, cannot be easily seen due to poor contrast between the kerb and cycleway surfacing.

The sloping footway, drainage covers, sloping footway and crossing paths, shown in Figure 4‑18, were perceived as hazards that could cause the wheelchair to turn over or tumble.

From observation and listening to the feedback from the participant a key problem for wheelchair users as it relates to the kerbing arrangements is the height more than the shape. These could be measured as this is the determining factor on whether they will be able to traverse them without tipping over.

Noise and light information measurements

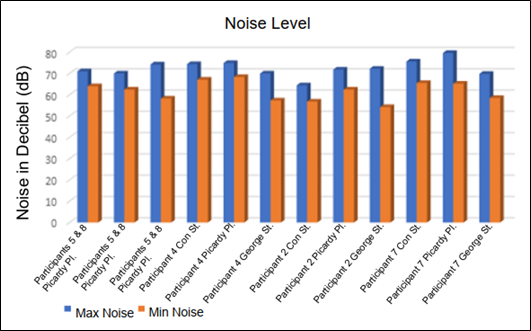

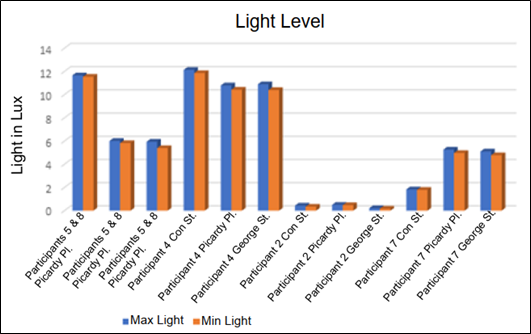

Information on ambient noise and light were collected at the three site visit location at the time of the site visits. The maximum and minimum noise and light levels at the time of the site visit were taken using hand-held noise and light meters. The ambient light was recorded in the 40k range, while ambient noise was taken over 1 minute to allow sufficient width of time window and band-width for data sampling.

It is noted that the ambient background noise in typical urban areas varies from 60 to 70 dB. Though, for some streets it reached 80dB.

Figure 4‑19 shows the maximum and the minimum noise levels for the three locations (Constitution Street, Picardy Place and George Street) at the time of the site visit with the study participants. The chart shows that the noise levels measured at Picardy Place ranged from a minimum 62.4 dB to the maximum of 79.6dB.

According to Participant 4, a hearing-impaired participant, they stated “a lot of Deaf people become deafer when they're outside” (see details in Sections 3.3.2 and 3.8.4). This was explained as being a masking effect of ambient noise for hearing aids; possibly resulting from automatic noise threshold compensation), and also for masking occurring in regular hearing itself, and particularly in amplified hearing where frequency filtering is not present.

Kerb Luminance and Contrast Analysis

Figure 4‑20 shows the maximum and the minimum light levels for the three locations (Constitution Street, Picardy Place and George Street) with participants with varying degrees of capabilities. Light level varies season to season, even day to day.

There is little evidence that the influence of the light level or resulting contrasts of kerbs and roadways or cycleways affect the visually-impaired participants and guide dogs from seeing or identifying the kerbs (see Section 3.3). The reported transcript sections where visibility issues were identified are given in Table 4‑1.

|

Section |

Issue |

Reason |

|

3.3 |

It emerged that identifying where the actual kerb of the crossings are located could be a significant problem |

When the tactile pavement is constructed, it may terminate at some distance before the location of the beacon post |

|

3.3 |

Sunlight causing difficulty to see lantern signal at controlled crossings |

A concern for participants with partial vision, reinforcing their overall frustrations with the challenges of locations and the positionings. |

|

3.4.1 |

Ambiguity of tactile pavements near kerbs were seen as sources of confusing and disorientation |

A very shallow kerb that then sloped down to a shallow angle might not be as easily identifiable as some as a steeper or higher one |

|

4.5.1 |

Flattened tactile paving with the kerbs along the cycleways |

The kerb height separating the road and the cycleway was fine except for what he described as a “mess” having pavement and cycleway flattened at the cycleway crossing with the push button unit |

|

4.3.3 |

It was highlighted that the kerb cannot be easily seen |

Kerbs bordering the cycleway (See Figure 4‑5) |

|

4.5.3 |

The appropriateness of the drop-down in those locations was unclear. |

The participant considered that the dropdown of the kerb was not distinct along the newly constructed cycleway and the adjacent road. |

|

4.4.3 |

A corresponding hazard for the visually affected |

Ascending and negotiating the kerb at the far side of the crossing point is also affected by the visibility of the distal (exit) kerb. |

Key Sound and Vision Measurement Themes

In summary, ambient sound levels are critical to the formation of situational awareness, particularly for very low vision people dependent on canes or guide dogs. The sound of traffic was reported to be used to locate the main roadway, thus orientating the pedestrian to the direction and location of building frontage.

In the case of very high ambient noise from traffic, pedestrians, shops and buildings, it was established that this could disorientate and impair function for those relying on hearing aids, due to the effect of frequency masking on unassisted (but low capability hearing), and on hearing aids. In addition, the directionality and audibility of audible crossing signals were affected by high levels of noise particularly at complex multi-section crossings where more than one signals was present. This was hazardous as it was possible to commence crossing the incorrect section when a signal from a nearby crossing was perceived as being adjacent.

High ambient sound (dB) levels and the complexity of noise can also mask quieter sounds, such as approaching cyclists, which were reported by the participants as a highly perceived hazard.

Taking the qualitative reported issues, photographic and video evidence and the objective illumination and contrast evidence together, it was concluded that the visibility of kerbs was dependent on a number of factors such as: distance of viewing, ambient light levels, weather conditions, colour, material dryness, and incidence of viewing angle. This principally affected wheelchair participants but was not significant in the case of very low vision individuals who relied on cane or dog assistance. The visual contrast of kerbs was not reported as a major problem but was part of a number of hazards that contributed to the overall perception of risk. This reflected the complexity of high-level visual perception and remains an area where further research could benefit the evidence base.

Discussion of Findings (Integrated Interview and On-site)

There were a number of findings reinforced by both interviews and site visits. For this integrated section the multi-capability issues are dealt with in a combined format, reflecting the entire experience, enriched by the site visit videos and commentaries.

The qualitative analysis of the combined corpus of transcripts for interviews of the participants revealed a number of difficulties and issues that were specific to capability (vision, hearing, thinking). However, it also emerged that many of these considerations were linked as a result of the effect of design and nature of kerbs and crossings and were, in fact, impacting multiple capabilities at the same time. For example, perception of the steepness (drop) of the kerb was a concern for visual impairment, when using sticks and guide dogs, but was also an issue for wheelchair users negotiating kerbs within the engineering parameters of safety of their wheelchair designs. The issues for both vision and hearing capabilities were therefore frequently co-located such that location and alignment of the participant for visual impairment was also linked to the form, layout and visibility of the nearside and far side kerb descent and ascent.

The purpose of the Phase 3 study was to investigate the role and configuration of actual kerbs within the build environment, building upon the foundations of the overall programme:

- Phase 1 Literature review and determination of research credentials;

- Phase 2 Formative methodology development and surveying of sites.

The Phase 3 investigations carried out consisted of:

- A collection of interviews with people with differing capability variations sampled from a matrix sample encompassing high, medium and low levels of capability, as defined by functional scales of vision, hearing and physical movement, thinking and systemic capability.

- A selection of site visits during which participants were asked to report on the considerations of crossing at identified sites, in situ, with video and audio recordings of their commentary as they progressed. Researcher participation in the site visits was confined to pre-decided schedule of basic questions and any utterances that were to ensure safety.

- The transcribed recordings of both interviews and site visit commentaries were thematically coded and then recoded once integrated together. The resulting summaries of the themes were prioritised on frequency or reference and the power of the method.

Multi-capability Issues with Crossings

Participants reported challenges with controlled pedestrian crossings which cross both a cycleway and carriageway. These issues were associated with relatively recently constructed pedestrianised crossings where they perceived the tactile paving was positioned too close to the crossing point, with no ramp or tail to the kerb edge. The users, both physically and visually impaired perceived this as a safety concern to people with reduced capabilities.

Those participants with reduced physical movement noted that kerbs they perceived as high with steep crossfalls to the carriageway crossing were the key challenges. For wheelchair users the dropped kerbs at the start of crossing; whether at controlled or any other area, constitutes a focus for stress in crossing the road due to the potential for tipping or falling over if the drop is too steep. In particular, the front caster wheels of wheelchairs are small in diameter and may jam into the kerb corner, even or especially when stabilisers were fitted that might foul the surface. Causally, the centre-of-gravity of the chair with user combined may be passed, causing tipping and falls. Wheelchair restraint straps were assumed to be in use.

Equally, ascending and negotiating the kerb at the far side of the crossing point (controlled or otherwise) presented similar issues. In this case, the centre of gravity could lead to tipping backwards during attempts to lift the smaller front wheels onto the kerb top. This was seen as particularly dangerous, as tipping backwards inevitably led to injury or unseating and presented a difficult recovery position in a live roadway that was dangerous, embarrassing, and could require assistance.

A corresponding hazard for both the visually affected and wheelchair users whose visual capability was good, was perceiving the kerb dimensions on the far side of the chosen crossing point. This was a risk issue as the individual who was crossing was committed once the crossing started and may not perceive kerb hazards until reaching the far side.

Additional complications accrued because of standing water in drain gullies, while snow or ice had the potential of visually obscuring the kerb dimensions, increasing the perceived risk. This was reported to be aggravated by poor visual contrast between kerbs and roadway and between kerb and pavement in various conditions.

All participants reported that if they judged the risk of crossing as at a specific location was too great they would look for nearby controlled crossings to achieve a safe crossing.

Concern was directed towards the timing of a crossing attempt because reorientation or visually searching the far side of the crossing while traversing was time consuming. When traffic signals changed or some undetected hazard approached this could lead to being stranded in the road. This generated some anxiety and apprehension, often leaving the potential user of the crossing waiting by the kerb, interacting with other crossers or blocking the passage of those behind, until they had a sufficient certainty they could cross safely.

Other challenges raised around the controlled crossings include broken or cracked, uneven, slab pavements and potholes. Participants reported incidents of the wheelchairs becoming jammed in potholes and being unable to extricate themselves without assistance. Potholes were particularly hazardous when close to kerbs where the wheels could stick in the holes. The participants noted that metal, slotted drains were perceived as a hazard and were occasionally sited at crossings. Such drains were also reported as an issue in negotiating kerbs and footways elsewhere as they trapped wheels.

However, no adverse reports were associated with tram lines. In some cases wheelchair users reported that they did not notice crossing them.

For wheelchair users in particular it was noted that sometimes there was insufficient time allowed for them to traverse controlled crossings comfortably. The insufficient crossing timing was reported to lead to difficulties and increased risk and stress. Psychologically, such time limited, countdown, situations are known to generate anxiety, stress and poor decision making.

For visually impaired users this is compounded when the auditory signals stops before they have reached the far side and they are unable to orientate themselves. They reported that at locations with multiple adjacent crossings the overlapping and changing of location of non-directional auditory signals can be disorientating and confusing. This could cause users to become lost or enter the carriageway at the wrong time.

Manoeuvring to locate and press the demand button was reported to lead to instability and disorientation. There was the potential for uncontrolled or involuntary incursion into the roadway, especially on the descent to the carriageway. Some push button unit positioning could require the wheelchair user to stop on the slope close to the carriageway leading them to attempt braking with one hand and pressing the button with the other, in an unstable configuration.

Where these crossings were shared between multiple different user types, such as cyclists and pedestrians, it was raised that reaching the button or aligning for crossing was challenging. The participants also noted that, while many citizens were accommodating and helpful, sometimes other crossing pedestrians were a hazard particularly if inattentive because of mobile devices. According to Participant 9:

Quote 29: “I would say sometimes, the other pedestrians can be a bit of a problem. Because sometimes when I’m using the walking stick (CANE), sometimes people can be really good and give you a wide berth and give you enough space to get over. But if there’s somebody trying to cross, you know, either with the chair or stick, that can be problematic, but that’s just people.”

There is a common emergent strategy that was necessary for most categories of capabilities when crossing at formal crossing points:

- Orientation to and location of crossing drop kerbs and push button units (avoiding pavements obstructions such as service chambers and potholes),

- Visual or auditory sensing for vehicles and the actions of other pedestrians,

- Visually and physically assessing the kerb depth on nearside and far side,

- If no present danger of vehicles were detected, crossing was initiated.

- If an immediate hazard was detected the user would wait in place for these to pass before crossing.

The strategy described above was not sensitive to quiet vehicles, such as cyclists or electric vehicles, for visually impaired users. This increases their perceived risk levels and chances of collisions with such vehicles. It was reported by all participant categories that it was their perception that cyclists frequently do not signal or stop to allow the people who are challenged in capabilities to cross. There was a belief that, in some instances, cyclists would continue through red lights on the carriageway when people were crossing the road with a green-man. Similarly, to the earlier discussion regarding adjacent multiple crossings, it was generally reported that there was a challenge where crossings were shared between cyclists, pedestrians, baby carriages, dogs, and other capability limited users. However, despite this, participants considered this combined risk as “expected as normal”.

Kerb strategies

For visually impaired participants kerb detection involved cane use or other means of developing or maintaining situational awareness such as sensory scanning, prior reconnaissance, the use of Apps, or assistance. This was particularly related to gaps at business entrances and private housing driveways, for example. The reported strategies involved choosing to progress along the pavement in a particular direction according to navigational information to assess crossing points and potential hazards. This was situationally related, depending on known orientation, familiarity and perceived location with respect to a mental, actual, or virtual map. Routes may have been planned in advance or could be informed by mobile applications using distance and landmark identification reports.

To maintain a centreline on the footway in such excursions visually impaired participants used a mixture of indicators. This included echolocation to identify solid shopfronts and pavement obstacles. However, necessary deviation was common and immediate in the case of the very low visually capable, even using guide dogs (See Section 4.5).

The finding of orientation for direction could also be managed by directional location of traffic noise and maintaining gradients. However, this strategy was reported as less effective in larger open spaces, such as complex pedestrianised areas. Participants reported that it was sometimes possible to orientate themselves directionally by using a crossfall towards the carriageway. Kerbs were usable as an indicator of the boundary if they could be detected using the cane, especially for individuals with low hearing capability.

Notably, the height of the kerb was deemed to be of low importance, the requirement was only that the kerb was detectable. A mental map was reported in some cases based on prior experience or for those comfortable with the use of compass directions and a prior knowledge of locale.

For all participants road construction work, or implementation of new layouts and designs, were identified as a source of frustration. For visually impaired users this changed their mental map of an area resulting in confusion and disorientation. For physically impaired users the temporary crossing points and passages were reported as being often poorly placed or constructed.

Weaknesses of the Study

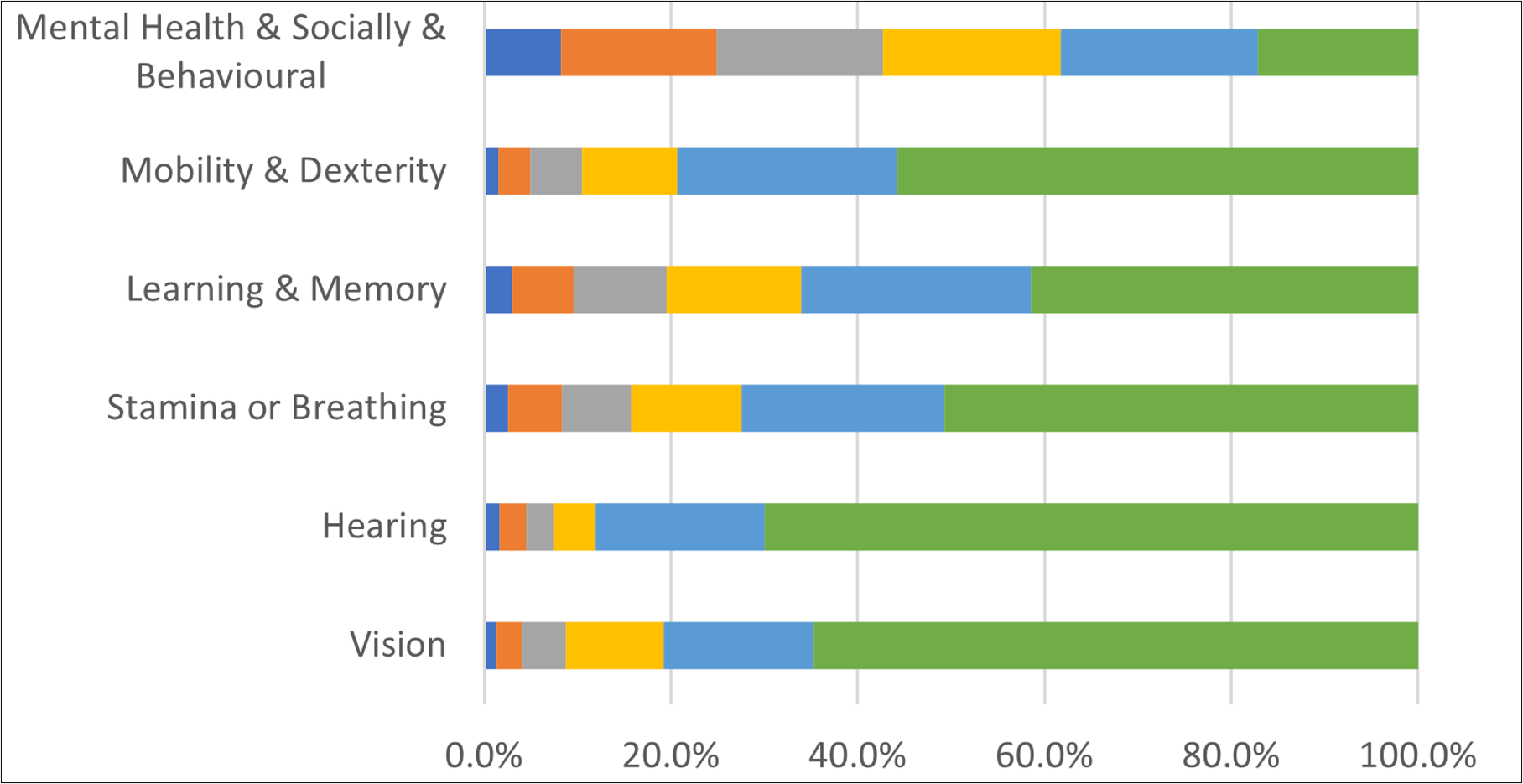

The ambition of Phase 3 was to represent the proportions of the Scottish population who reported difficulties in daily life at various levels of severity in the functional areas (see Figure 4‑21). These statistics were calculated and presented in Phase 2 report along with the sampling approach and capability levels.

The participants in Phase 3 were consistent with the analysed data from the Family Resources Survey (2019-2020) in that difficulties in daily life due to specific functional origins were strongly related to age with vision, hearing and mobility being predominant in the 55+ age groups.

This is important as; depending on location, more than 50% of the UK population is now over the national average age of 43. Priority was therefore given to low and very low level of capability in vision, physical movement, hearing, systemic and thinking (see Figure 4‑21). It was also important to represent age groups and gender.

However, identifying and arranging the range of participants for site visits with the study period was challenging. Participants were volunteers who were agreed to participate during a normal working day.

The site visits were carried out within October and November, although site visits were planned and agreed for later months over the subsequent winter and spring these were cancelled due to personal participant and weather conditions. This led to a reduction of data gathering opportunities. In original matrix sampling in online interviews there were ten participants, as described in Table 3‑1, of which five participants joined the site visits.

As can be readily seen in the video analysis section, weather conditions and ambient light were variable, and the kerbs were often wet. Traffic conditions, and so noise, also varied.

The study could not deliver a complete set of results without a high level of generalisability, as was discussed in Phase 2. This is particularly true if all the potential variables, such as: weather, time of day, season, site characteristics, and individual variabilities (within and between individuals) are taken into account.

The study in Phase 3 only sampled individuals with low to very low capabilities. However, it is considered likely that individuals with higher levels of capability might encounter similar, if attenuated, effects as those found from the participants. The possession of higher levels of capability could be expected to reduce levels of stress, reduce the requirement for prior preparation and real-time assistance, and increase the tolerance for other users’. In particular, thinking issues might occur in conjunction with the identified design issues discussed, leading to higher levels of risk and reduced overall capability.

Although numerical ranges and specific kerb parameters were recorded, many comments pertaining to kerbs were qualitative. Further trials of people exposed to physical kerb layouts would be necessary to converge on accurate numerical values for kerb properties. This could be achieved safely in a laboratory environment using systematic variation of parameters such as: variable surfaces, gradients, materials, shapes, and variable heights.

However, a number of findings were robust and reliable in the thematic analysis and are backed up by qualitative evidence (recorded statements and actions) at the sites. These constitute a set of robust, explainable, repeatable and complete findings linking individual capabilities to kerb and site properties, that were backed by a documented evidence trail, and represent lived experience.

Key findings

It was clear that despite the initial focus on crossing at site with particular selected properties, most participants immediately fell back on default behaviour. Typically, on being required to cross at a specific point they would decline and begin a commentary on alternative strategies, often finding a more acceptable place to cross, and demonstrating how it was better. These commentaries provided rich and detailed insights about the lived experience of individuals’ capability variation. The holistic results then can be summed up as covering a wide range of interrelated physical contexts and considerations.

We determine that this more closely resembles the actuality than considerations of single factors, such as kerb height or shape, alone. Salient inferences are listed here:

- A number of difficulties and issues were identified that were specific to capability (movement, vision, hearing, thinking).

- Many of these considerations were linked as a result of the effect of the design and nature of kerbs and crossings and were, in reality, impacting multiple capabilities at the same time.

- The kerb height was a concern for visual impairment but only for detection when using sticks and guide dogs. It was also an issue for wheelchair users negotiating kerbs within the parameters of safety of their wheelchair designs and capabilities.

- The issues for movement, vision and hearing capabilities were, therefore, frequently collocated, such that location and alignment of the participant for visual impairment was also linked to the form, layout and visibility of the near-side and far-side kerb descent and ascent of a roadway.

The general strategy employed by those with low capabilities, whether visual, physical or other, was driven by the necessity for safety when faced with challenging kerb sites. In general, this started with a search for a safer location to cross, the search based on noise, surface properties and perceived safety of the road layout. This often defaulted to seeking in either direction for an established or controlled crossing. Since complexity and hazards increased at such “safe” crossing points, they had to be discovered anew – with apprehension; or dealt with based on prior experience of specific or similar crossing points.

This was well illustrated by considering the common crossing issues that were recounted (and demonstrated) by the low capability individuals. Many of these issues were also likely to present challenges to higher capability and combined capability individuals.

Manoeuvring and orientating with respect to the crossing was a pre-eminent initial requirement. Physical and perceptual challenges resulted from complex crossings where pedestrians, cycleways and street traffic were forced to interact dynamically. Key challenges that were reported included physical dimensional and mechanical issues with wheelchairs (see Section 3.9) and a range of tactile and perceptual issues related to the detection of hazardous layouts and assistive road markings and signal equipment. It was reported that significant negative emotions and apprehension was generated by these situations.

Perceiving the kerb haptically or visually was vital but making a judgement about the traverse-ability of the kerb on the other side of the road was deemed equally as important. Guide dogs were useful but capable of being confused and sometimes made actions whose usefulness were dependent on the quality of communication with their participant.

Controlled crossings presented a complex set of interrelated difficulties which could raise anxiety levels. However, controlled crossings were also considered to be relatively safe.