Literature Review

Demographic, Work Patterns and Location Choice Context

This section includes contextual information on demographic trends in rural depopulation and rural employment structures.

Demographic Projections

The National Records for Scotland’s (NRS) mid-year population estimates highlight that for much of the ten years between 2012 and 2021 population in Scotland’s remote small towns and rural areas was in decline.

In remote rural areas, NRS’s Population Estimates by Urban Rural Classification, 2001-2021 showed a population decrease by 1.0% between 2011 and 2020, compared to increases of 3.1%, nationwide and 8.4% in accessible rural areas. The population of remote small towns decreased by 3.6% over the same period.

In remote rural areas, the trend changed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Between mid-2020 and mid-2021 the population in these areas increased by 1.6%. Net migration increased from 120 to 6,170 in the year to mid-2021. Growth in remote small towns remained negative, with a 0.2% population decrease in the twelve months to mid-2021.

Mid-2021 Small Area Population Estimates, Scotland also suggests populations are aging everywhere in Scotland. Between 2020 and 2021, natural population change alone would have resulted in a reduction of Scotland’s population by 14,500 people. However, the population increased by 13,900 people overall, primarily driven by net international migration of 18,900 and net migration from the rest of the UK of 8,900. Population aging is more prominent in rural and islands areas. The percentage of local authority data zones in which median age increased in the previous decade varied between 55% in Dundee City and 97% in Na h-Eileanan Siar.

Demographic projections published in Copus (2018) aimed to quantify the extent of the challenge faced by remote areas in Scotland in the future. These projections focus on sparsely populate areas in Scotland, defined as areas where the population accessible within 30 minutes travel time is less than 10,000 people. It should be noted that not all remote rural areas are part of Scotland’s sparsely Populated Area.

The paper notes that the population of Scotland’s sparsely populated areas is in a “negative spiral of decline”. Population projections developed by the study highlight that population decline in these areas could amount to 28% by 2046 against a 2011 baseline. A breakdown by sub-region is shown in Table 2‑1.

|

Sparsely Populated Area |

2011 |

2046 |

% change |

|

Northern Isles |

13,430 |

10,860 |

-19% |

|

Western Isles |

13,580 |

9,250 |

-32% |

|

NW Highlands |

39,210 |

28,400 |

-28% |

|

SE Highlands |

20,600 |

15,510 |

-25% |

|

Argyll and Bute |

42,440 |

29,530 |

-30% |

|

Southern Uplands |

8,270 |

5,780 |

-30% |

|

Total Scotland sparsely populated area |

137,540 |

99,350 |

-28% |

Source: Copus (2018)

The decline is expected to affect age groups differentially. Working age populations are estimated to shrink by 33%. Dependent groups are projected to experience a lesser rate of decline, with the number of children reducing by 19% and over 65s reducing by 18%. This is expected to result in an increase in dependency rates from 0.6 in 2011 to 0.74 in 2046. Policies targeted at reducing depopulation and attracting in-migration need to redress this balance to target push and pull factors for the working age population.

Copus (2018) states that recovering growth in these areas would depend upon in-migration at a rate of 10 migrants per 1,000, with emphasis on people of child-bearing age to ensure longer term sustainability. These rates are currently only exhibited in Edinburgh, Midlothian, and Stirling.

Rural Ways of Working

Exploring the role interventions to improve connectivity can play in improving rural employment opportunity requires some understanding of rural industries and employment structures.

There are some noticeable differences in working patterns, employment and business demographics in Scotland’s rural areas compared to the rest of Scotland which are explored in a Rural Scotland Key Facts 2021 report.

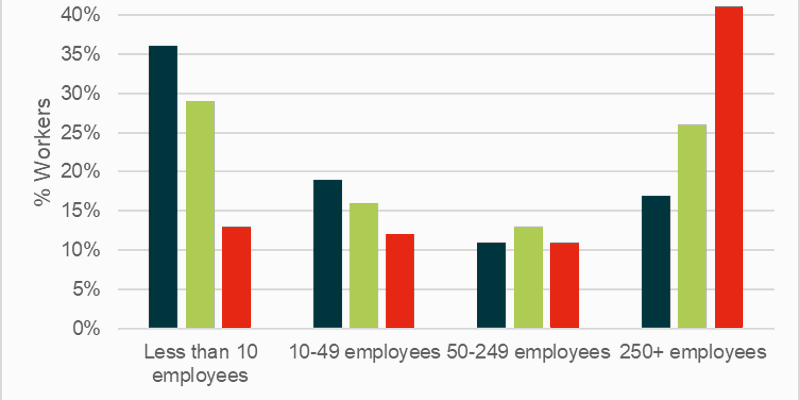

Figure 2‑1 shows differences in the proportion of employment provided by businesses of different size by area type using the 3-fold Urban Rural Classification. The analysis is based on data from the Inter-Departmental Business Register, and as such classifies employment by business rather than employee home location.

Source: Rural Scotland Key Facts 2021

In rural Scotland, a greater proportion of employees work in micro-businesses, which consist of between 0 and 9 employees, than in the rest of Scotland. 36% of employees in remote rural areas and 29% in accessible rural areas work in micro-businesses, compared to 13% of the rest of Scotland.

Overall Small and Medium-sized Enterprises, defined as businesses employing between 10 and 249 people, account for 66% of remote rural employment compared with 36% outside rural areas. By comparison only 17% of employees in remote rural areas and 26% in accessible rural areas work in large businesses (more than 250 employees) compared to 41% of the rest of Scotland.

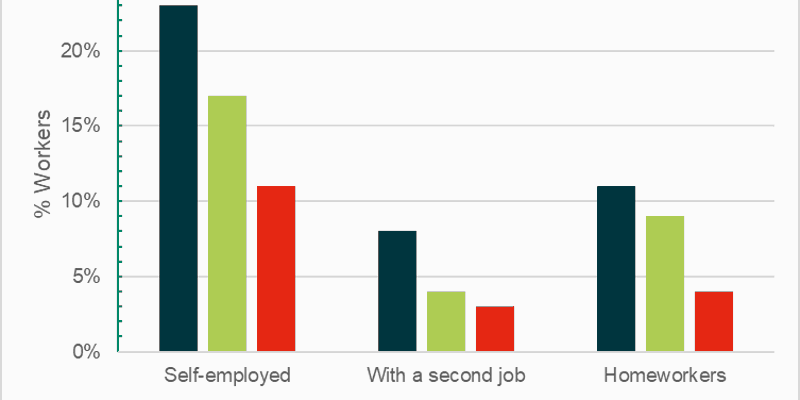

As shown in Figure 2‑2, the proportion of workers who are self-employed, have a second job, and work from home is also higher in remote rural areas than in other parts of Scotland. It should be noted that working from home figures are pre COVID-19.

Source: Rural Scotland Key Facts 2021

A breakdown of rural employment by sector is shown in Table 2‑2. Rural Scotland has a more diverse spread of sectors compared to the rest of Scotland, where nearly 50% of employees work in the public or financial sectors. In remote rural Scotland there are significantly larger proportions of workers in the accommodation and food services, and agriculture, forestry, and fishing sectors than accessible rural areas and the rest of Scotland. Accessible rural areas have larger percentages of people employed in construction and manufacturing than both remote rural areas and the rest of Scotland.

|

Employment Sector |

Remote Rural |

Accessible Rural |

Rest of Scotland |

|

Public |

17% |

17% |

23% |

|

Education, Health, and Social Work |

5% |

7% |

10% |

|

Financial and Other Activities |

15% |

17% |

23% |

|

Accommodation and Food Services |

15% |

9% |

8% |

|

Transport, Storage and Communication |

5% |

5% |

7% |

|

Wholesale, Retail and Repair |

10% |

12% |

15% |

|

Construction |

7% |

8% |

5% |

|

Manufacturing |

8% |

10% |

7% |

|

Mining & Quarrying, Utilities |

3% |

4% |

2% |

|

Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing |

15% |

12% |

0.5% |

Source: Rural Scotland Key Facts 2021

Summary of Key Points

- Sparsely populated areas in Scotland are projected to see substantial population decline, with some projections indicating an overall reduction by 28% between 2011 and 2046.

- Based on NRS mid-year population estimates the population in remote rural areas decreased by 1% between mid-2011 and mid-2020. Between 2020 and 2021 population in these areas increased by 1.6%, driven by a marked increase in net-migration.

- Differential impacts by age groups are projected to result in substantially increased dependency rates. Policies aimed at creating sustainable communities will therefore need to target increased in-migration of young and working age adults and families.

- Remote rural employment patterns differ substantially from the rest of Scotland with a higher proportion of the workforce employed in micro-businesses, self-employed, holding several jobs and working from home.

- Employment by sector is more diverse than elsewhere in Scotland and employment in the accommodation and food services and agriculture, forestry and fishing sectors is more prominent.

Evidence on Research Questions

Household Location Choice Factors

This section introduces the factors influencing household location choice more generally and in rural Scotland. This is intended to provide context to the discussion of the role transport and digital connectivity play. A wider understanding of the choice mechanisms is particularly pertinent given the secondary nature of connectivity as a service. Transport and digital infrastructure enable access to opportunities and services and hence an understanding of how individuals prioritise wider factors is important when considering their role.

General Household Location Choice Factors

Household location choice factors can be broadly summarised as:

- Decision to move is influenced by life cycle stage, existing household tenure, and significant life course events.

- Workplace location is becoming a less prominent factor when choosing household location.

- Uncertainty whether preferences seen in COVID-19 (for greenspace and potential for home working) will persist.

- Young people are more likely to place importance on cost and accessibility to workplace in a location choice decision, whereas older people are more likely to value greenspace/countryside and neighbourhoods.

When individuals are choosing household location, Lee & Waddell (2010) suggest this can be represented as a two stage nested logit model – firstly a decision on whether to stay in the existing location or relocate, and secondly an evaluation of the alternatives relative to the previous residence. It should be noted that the respective factors relating to these stages are often referred to as push factors and pull factors in the literature.

Lee & Waddell (2010)’s study in the Puget Sound Region of Washington State, USA notes that the stage in the life of the individual will have an impact on the decision to relocate, with young adults in their twenties and thirties the most mobile section of the population. Household tenure and size are also important factors, with those in larger and owned properties much less likely to relocate. A third decision factor is significant life course events which can include starting a family, divorce, children moving away, and education and work opportunities. These factors are supported by a study by Eluru et al (2009) derived from a survey conducted in Zurich, Switzerland. The study found factors for moving home can fall into three categories: personal (changes in family circumstances), household (composition and ownership), and commute (mode and distance) related variables.

A stated preference study by Kim et al (2005) in Oxfordshire, UK, found that transport factors are important in a decision to move home, with increases in travel time to work, travel costs to work and travel costs for shopping all associated with an increased probability of moving. Other factors which influence this decision are the population density, quality of schools and the house price itself.

Turning to the location choice for the new residence, a study by Chen et al (2008) using data from the Puget Sound Region in Washington State, USA, found that previous residential location is influential in deciding which factors are most important to an individual when making a location choice decision, stating that “Households with the same set of socioeconomic and demographic characteristics could display strikingly different tastes in their residential location selection process because of the differences in prior locations”. For example, this could mean where individuals have been brought up in areas with poor transport connectivity, they place less importance on this as a decision factor than those who are used to having stronger transport connectivity.

Choice of work could also be a factor for deciding residence location. However, research by Waddell et al (2006), again using data from the Puget Sound region of Washington state, USA, found that 80 per cent of workers within an urban area chose their residence first, then choose their workplace.

In the UK, Clarke (2017) found that economically driven internal migration over the previous two decades has been in decline, with fewer people changing their work location than 20 years prior. Declines in internal migration are also down to young people, graduates, and private renters moving less. In 2001, 1.8% of graduates moved employer and region, but in 2016 only 1% did. For private home renters 2.6% moved employer and region in 2001, while in 2016 this fell to 1.5%, when it is these groups who are traditionally expected to be the most mobile.

In a more recent study based on data from the Quality of Life index, Totaljobs, 2023 reported that despite high satisfaction levels with their current place of residence 65% of workers are willing to relocate to a different city. The study suggests that cost of living could be a key driver of location choice, with 74% of workers saying they are concerned about their financial situation. Young people in particular identified living costs as a location choice factor, with 29% of Zillenials considered moving to a cheaper city (compared with 18% of 35-54 year olds and 12% of over 55s). The study identified five top lifestyle considerations that would motivate workers to move, affordable living costs (36%), a good job offer or plenty of job opportunities (35%), affordable housing or rent (30%), a better work-life balance (26%) and a family-friendly area (22%).

COVID-19 has further entrenched this trend. Randstad RiseSmart UK (2020), an outplacement firm, found that in November 2020 49% of workers (the longitudinal study polled 36,000 UK adults between 2016 and 2020) said location was one of the top five factors in their choice of work and employer, up from 35% immediately pre-pandemic. Despite technology facilitating working from home, COVID-19 reversed the pre-pandemic trend which saw the above statistic decline from 40% in 2016 to 35% at the start of the pandemic. Randstad attributed this to reduced willingness to accept long commutes following the pandemic.

A UK based study by Santos (2022) found residential location choice is influenced by a number of factors which have grown in prominence since the COVID-19 pandemic. The study employed a discrete choice experimental set-up to test consumer preferences for residential locations. Locations supporting hybrid working patterns were valued most. House price and garden size were also important. However, journey distances to both work and services remained a key consideration in the location choice decision.

Variation by demographic characteristics and location

Schirmer et al (2014) undertook a review of residential location choice factors and models. The study found that households’ preference for specific land use mixes varies with life stage. Young households typically favour high population density locations, whereas families and higher income households typically value low density residential population densities. Proximity to, and density of, education, services, retail and local transport facilities was valued by all. Whether proximity to road or public transport infrastructure was preferred depended on household car availability. Density of road and rail network as a source of noise and pollution was perceived as negative by all groups. Longer commutes were also valued negatively.

Thomas et al (2015) examined data from YouGov polls in cities, suburbs, and rural hinterlands in England and Wales to understand push and pull factors for location decisions through examining data describing why people choose to live where they do, and what they dislike about their current place of residence. As part of the poll, respondents were asked to state the three main reasons why they chose to live in their neighbourhood.

The study found that for the youngest age group (18-24 year olds) factors related to familiarity, including “I grew up in the neighbourhood” (28%) and “To be close to my friends/family” (26%), were the most important. Cost of housing (20%) and vicinity to place of study (17%) were also important to this group. The most common reasons among 25-34 year olds were “To be close to my friends/family” (32% of respondents), “The cost of housing” (30%) and “To be close to my workplace” (24%). For older adults (35-54 year olds) “To be close to my friends/family” (27%) took second place to the cost of housing (30%).

Reasons for choosing their neighbourhood saw a substantial shift towards factors related to the quality of the environment and housing for 55+ year olds. “To be close to countryside/green space” was the most widely noted location choice factor for people in this group (30%), followed by the size or type of housing available (29%). However, the cost of housing (28%) and “To be close to my friends/family” (27%) remained important to this age group.

Availability of public transport was of secondary importance. 8% of 18-24 year olds, 15% of 25-34 year olds, 13% of 35-54 year olds and 16% in the 55+ age group ranked this among their top three reasons for moving to their place of residence.

The study also examined how location choice factors varied by the three area types examined, city centre, suburb and hinterland. Vicinity to work, shops, leisure and entertainment and public transport all declined in importance when moving away from urban centres. Vicinity to the countryside increased.

Results from the study are presented in full in Table 2‑3.

|

Reason |

18-24 |

25-34 |

35-54 |

55+ |

|

I grew up in the neighbourhood |

28% |

18% |

21% |

13% |

|

To be close to my workplace |

16% |

24% |

19% |

14% |

|

Studying in the neighbourhood |

17% |

3% |

1% |

0% |

|

To be close to restaurants/leisure or cultural facilities |

6% |

9% |

4% |

3% |

|

To be close to my friends/family |

26% |

32% |

27% |

27% |

|

The cost of housing available in the neighbourhood |

20% |

30% |

30% |

28% |

|

Availability of public transport in the neighbourhood |

8% |

15% |

13% |

16% |

|

To be close to good schools |

2% |

8% |

13% |

8% |

|

To be close to local shops |

7% |

7% |

10% |

12% |

|

The safety and security of the neighbourhood |

11% |

9% |

17% |

17% |

|

The quality of the built or natural environment of the neighbourhood |

7% |

8% |

11% |

15% |

|

To be close to countryside/green space |

7% |

11% |

20% |

30% |

|

The size or type of housing available in the neighbourhood |

12% |

14% |

21% |

29% |

Source: Thomas et al (2015) from 2015 YouGov poll of 2080 GB residents

Location Choice in Rural Areas

Push and pull factors for household location choice were discussed in section 'General Household Location Choice Factors'. This section summarises evidence showing which of these factors are most prominent in rural migration decisions in Scotland.

In 2010, the Scottish Government (2010) published an in-depth report outlining ‘Factors Influencing Rural Migration Decisions in Scotland’, and how these vary by age group and life stage. The report drew on a comprehensive review of literature published on the subject since 1999.

Push, pull, stay, return factors as identified in the report for four different demographics: young people, families, people who are economically active, and older people, are listed below.

Factors relating to young people

For young people, push factors (away from rural areas) include:

- Employment – lack of job opportunities and choice.

- Higher Education – limited options.

- Housing – lack of affordable housing and high demand from older people.

- Desire for independence.

- Leisure facilities – poor availability and choice.

- Shops and services – lack of choice and growing number of closures.

- Public Transport – poor connections and high cost.

- Family pressure – expectation to start a career in an urban area.

- Perceptions – urban lifestyles more attractive and rural communities do not align with values.

- Social detachment.

For young people, pull factors (to rural areas) include:

- Local family ties or personal relationships.

- Job opportunities.

- The environment/scenery.

- Access to affordable housing.

- Perceived better quality of life in rural areas – more relaxing or outdoor activities available.

- Revived interest in Gaelic language and culture.

For young people, stay factors include:

- Securing a good job locally.

- Local family connections.

- Appreciation of high quality natural environment.

- Sense of attachment to rural area – through social or hereditary links.

- Ambition to start a family over academic or career ambitions.

- Strong sense of community.

- Parental expectations and ambitions.

For young people, return factors include:

- Access to appropriate jobs and vocational training.

- Affinity with local area – own identity is tied with that of the area, ability to identify with other people from area.

- Good contact with people and organisations in area.

- Social and family ties – including caring responsibilities.

- Perception that improvements have been made to local facilities and services.

- Lack of affordable housing in urban areas.

- Revival of the Gaelic language and culture.

- Appreciation of the rural lifestyle.

Factors relating to families

For families, push factors (away from rural areas) include:

- Housing – shortage of affordable larger housing.

- Shops – closure of local shops.

- School – lack of school and difficulties in accessibility.

- Medical and child-care services.

- Lack of lifestyle choices.

For families, pull factors (to rural areas) include:

- Environment – better for raising children than urban areas.

- Local family ties.

For families, stay factors include:

- Desire to safeguard children’s education and not create unnecessary upheaval.

For families, return factors include:

- Family ties.

- Perception a rural area is a good place to bring up a family.

Factors relating to people who are economically active

For people who are economically active, push factors (away from rural areas) include:

- Employment – lack of jobs with compatible skills or with good pay and security.

- Weak private sector – entrepreneurs tend to start businesses elsewhere.

- Public transport – lack of links to large job markets.

- Parental expectations and ambitions.

- Cost of living – perceived as higher in rural areas.

For people who are economically active, pull factors (to rural areas) include:

- Access to specific jobs – such as oil and gas work.

- High quality natural environment and availability of a range of activities.

- Knowledge and familiarity with area.

- Access to affordable housing.

- Perceived lifestyle improvements – safer and being closer to family.

For people who are economically active, return factors include:

- Availability of suitable employment.

- Affinity with the region.

- Family ties and care obligations.

- Social ties – strong sense of community.

- Appreciation of rural lifestyle.

- Desire for a lifestyle change and better work-life balance.

Factors relating to older people

For older people, push factors (away from rural areas) include:

- Limited supported and residential accommodation.

- Poor access to services – particularly healthcare and leisure.

- High turnover of healthcare practitioners – low expectations.

- Social isolation – distance from family.

- High cost of living – particularly fuel.

For older people, pull factors (to rural areas) include:

- High quality natural environment and scenery – tranquillity and perceived better quality of life.

- Knowledge and familiarity of specific area.

- Access to low cost housing.

- Change of employment status – being close to employment no longer required.

In summary, the review showed the enhanced emphasis on factors relating to lack of opportunity, including around employment, services and amenities in rural out-migration decisions. Younger age groups in particular were observed to leave rural areas in pursuit better access to employment and education, to gain new experiences, and expand their freedom and autonomy. Key points were:

- Factors related to access to employment opportunities were important for young people and people who are economically active.

- Access to higher education was a push factor for young people.

- Factors related to the availability of affordable housing were important for young people in particular, and to some extent for other groups.

- Poor access to services was also a push factor for all groups, although the emphasis varied, with young people emphasising access to shops and leisure services, families lacking schools and medical services and older people pointing to a shortfall in medical and leisure services.

- Poor public transport represented a push factor for young and economically active people.

For context, this report was written at a time when “more people have been moving into rural Scotland than have been moving out” and “rural Scotland experiencing higher levels of migration-related growth than the rest of Scotland”, although a focus of growth on accessible rather than remote rural areas was noted.

Unemployment, low paid jobs and declining rural industries

The Scottish Government (2010) considered employment as both a push and pull factor in different context for different people. It can be considered a push factor in contexts where the jobs available in rural areas do not align with the interests of the individual and can affect people at all stages of life including school leavers, graduates, and those already economically active. Particular issues with rural jobs which mean they act as a push factor include poor pay, due to a weak private sector, and lack of security, due to prevalence of temporary contracts and agency work. However, the report also argues that the presence of jobs which align with a person’s skillset can be a strong pull factor to a rural area.

Karcagi-Kovats et al (2012) reviewed EU member states’ strategies on addressing rural population decline. The depopulation factors most commonly identified in these strategies were ageing population and unemployment, living conditions, social and public services, low salaries, and declining agriculture. The paper notes that in the UK national rural development programme, the following factors were identified:

- An ageing population.

- Living conditions.

- Social and public services.

- Women and young people.

- Declining agriculture.

The review concluded that stabilising rural populations requires diversification of activities away from agriculture and general improvements to the quality of life. Rural development policies need greater focus on economic and social elements, and the ecological impacts of rural depopulation require consideration in greater depth.

The paper quotes sources from the wider literature on the subject, which suggest that the function of rural areas could be classified by (i) Agriculture and agribusiness and (ii) Rural services. These functions often conflicted.

Low availability of public services/amenities

Declining populations are associated with a loss of local services such as hospitals, education, leisure, and recreational sites which are centralised due to lack of ‘critical mass’, and with time the population which relies on these services will relocate to areas where they are more accessible. Limits to the availability of public finance represent an additional constraint in this context.

Nielsen et al (2012) suggest the ageing population in rural areas is skewing the service provision offer away from young people, which is creating an issue with retaining this group. In some areas the situation is exacerbated by in-migration. A discussion on the subject of Internal Migration in Scotland and the UK (2020) used Argyll and Bute as a case study. The local authority in this area, which is a popular retirement location, regularly reports significant skills gaps and unfilled vacancies in areas such as health and social care, where there is greater demand due to the population profile.

There is some evidence to suggest that satisfaction with services can be higher in rural areas. Using findings from the Scottish Household Survey, Place-based policy approaches to population challenges: Lessons for Scotland (2022) found that there was no evidence that perceptions of public services were systematically weaker in remote and Island Local Authorities (LAs). While factual evidence regarding the quality of services in remote and Island communities compared with the rest of Scotland was mixed, satisfaction with public services tended to be higher in these LA’s than in other parts of Scotland. This was true, even for public transport. The paper outlines the following limitations to the analysis:

- Aggregation over Local Authority areas prevents insights regarding variations by local area, specifically understanding of the influence of local perceptions on population trends over time.

- A gap in understanding regarding the role perceptions of what services might be like, play in people’s in-migration decisions or to what extent actual poor local services performance has motivated out-migration.

However, at the general level the reports concludes that it is unlikely that population decline in some rural areas was driven by poor perceptions of public services.

The Scottish Government (2010) report on rural migration undertook a review of location choice factors in remote rural areas. While the factors identified in this report were not based on a comprehensive survey, the report collates evidence from a large number of local studies. This may help address the limitations listed in above source. The report lists a lack of services and amenities as a push factor for people of all demographics. For young people the lack of higher education institutions and poor choice in leisure and recreational facilities caused people to move away for better opportunities. For families, the lack of childcare services and difficulty in accessing schools was determined as a push factor in a 2004 study of migration in North Lewis and Roxburgh. For older people the lack of supported and residential accommodation and poor perceptions of healthcare services were found to be push factors in a 2009 study in Orkney.

Lack of Affordable Housing

Scottish Government (2010) concludes that the need for more housing is a key theme in rural location decisions for both younger and older people. The report quotes evidence from a 2009 study in the Highlands & Islands which found that lack of affordable and low-cost housing and a lack of choice in the housing market are particular challenges for young people. Young people are disadvantaged in housing markets because they are “continually competing with others with deeper pockets, be they older residents with established careers and smaller mortgage requirements, or retirees looking for a rural retreat”. For older people, push factors relate to high costs and poor access to housing maintenance.

In addition, the report highlights the following issues with relevance to migration:

- The housing needs for in-migrants could be better supported, for example through offering temporary accommodation.

- The impact of second home ownership on rural housing markets presents a challenge.

There is evidence from the UK House Price Index (2022) for Scotland that house price growth is significantly higher in many remote and island areas compared to the Scottish average. Table 2‑5 shows the percentage difference in prices between October 2022 and October 2021 for local authorities with the largest portion of their population in remote rural areas, based on Scottish Government Urban Rural Classification 2020. Predominantly rural areas experienced substantially higher growth in house prices than Scotland as a whole.

|

Local Authority/Area |

% Population Remote Rural (2020) |

% Difference in House Prices (October 2021 – October 2022) |

|

Na h-Eileanan Siar |

72.5% |

37.9% |

|

Shetland Islands |

70.4% |

18.3% |

|

Orkney Islands |

66.5% |

20.2% |

|

Argyll and Bute |

43.2% |

21.3% |

|

Scotland Wide |

5.5% |

8.5% |

Summary of Key Points

- Household location choice is a two-stage process, first the decision to move is made, second the choice of the new residential location is made.

- Recently, the cost of living has been a key consideration in making the decision to move and location choice in the UK, particularly for young people.

- Decision to move is influenced by:

- Life stage, with young adults in their 20s and 30s more likely to move.

- Household composition and ownership, with larger and owned houses less likely to move.

- Personal factors such as household formation and resolution, and education and work opportunities.

- Transport considerations are secondary but reflect mode preference.

- Location choice is influenced by property price, population density, previous residential location, education opportunities.

- Availability of work is an enabler rather than a motivator and of declining importance as a motivator.

- Choice factors vary by age, with evidence that:

- 18-24 year olds are motivated primarily by factors relating to familiarity with surroundings and people, cost of housing and vicinity to education.

- For 25-34 year olds factor related to closeness to friends and families, the cost of housing and closeness to work opportunities were most important.

- For the 55+ age group closeness to the countryside and the quality of housing were more important.

- While overall satisfaction with services is high in remote rural areas, access to specific services, issues related to access to specific services played a role in location decisions. Lack of employment and education opportunities were important push factors for young and working age people. Access to schools and childcare were a push factor for families. Poor access to services particularly healthcare was a key motivator for out-migration among older age groups. Limited access to services, shops and leisure opportunities featured for the young. Poor public transport also represented a push factor for some groups.

- Availability of housing is a key constraint for initiatives looking to retain and attract population to rural areas.

To what extent do Digital Connectivity and Physical Mobility (i.e. transport) impact on location decisions for people and businesses

This section explores the importance of transport connectivity in location choice and differences in perception of what ‘good’ transport connectivity looks like. The section also discusses the role of digital connectivity in supporting the vibrancy of small businesses, who represent key employers in rural areas (following conversations with the client, business location choice is only being viewed through the lens of household location).

Transport Connectivity

Evidence on the importance of transport connectivity in household location choice decisions was mixed.

Research by Nationwide found that good transport connectivity, if not a location factor in itself, increased the value of a property. The premium paid for properties 500m from a rail or subway station in Glasgow, compared to 1,500m away, increased from 3.5% in 2019/20 to 7.2% in 2020/21.

In rural areas, experience from the Borders Railway, as detailed in the Year 1 Evaluation (2017) showed the influence of improved transport connectivity on household location choice decisions. A survey of users found that 52% of users who had moved house since the line reopened stated the railway was the main factor, or “one of a number of important factors” in their decision to move to their current address. 64% of those who moved to the Scottish Borders said they would not have moved to their current address if the railway had not reopened.

However, there is considerable evidence that other factors matter more. Following a review of empirical studies reporting in the literature and a housing market estimation study in the Netherlands, Zondag & Pieters (2005) conclude that:

- When making the decision to move households are less likely to move away from accessible locations.

- When looking for a new location travel time variables will affect the size of the search area.

- For many households, the accessibility of a specific location is not a significant location choice factor.

It should be noted that in the Netherlands accessibility changes between regions are comparatively small.

This finding is widely supported by the literature. Similar work by Molin and Timmermans (2003) in the Benelux (Belgium, Luxembourg and Netherlands) confirms that accessibility considerations are significantly less important than housing or neighbourhood attributes and this is confirmed by a report by Kryvobokov & Wilhelmssen (2007) focused on Donetsk.

A paper reporting the calibration of a household location choice model for Leicestershire by Revill & Simmonds (2011) states that “the accessibility variable is essential” and consists of components relating to accessing different types of opportunity, including jobs, healthcare or shopping. However, the model found that the cost of the location was significantly more important than the accessibility, such that a household is 0.56% less likely to choose a location for every £1 per week increase in location cost relative to the alternative but only 0.03% less likely to choose a location for every one minute worsening in accessibility relative to the alternative.

The lack of emphasis placed on transport factors in the literature reflects transport’s role as a supporting service, which facilitates access to other opportunities and services, rather than being an end in itself. Charles (2010) describes transport as a derived demand with users of transport “primarily consuming the service not because of its direct benefits, but because they wish to access other services”.

Hence transport connectivity needs to be considered not simply as a location choice factor in itself but also more specifically in the context of access to services and opportunities it enables. According to Marchetti (1994) the average time people spend commuting to work in a day will tend to approximately one hour over longer periods of time. This equates to a journey to work of half an hour. As technology advancements have enabled faster transportation, this has resulted in increases in average distance travelled but travel time has remained roughly constant.

By this argument, the availability and speed of transport connections substantially influence household and employment location patterns. In remote rural areas a half hour travel time to employment opportunities in key centres cannot be met. Based on the 2019 Scottish Household Survey Travel Diary, 22% of workers in these areas have a journey to work longer than 30km, compared to 18% in accessible rural areas, 14% in remote small towns and 11% elsewhere. Given the sparser distribution of employment opportunities in the rural context, Marchetti’s constant therefore highlights the importance of transport in defining constraints on the acceptable distance of household locations.

Variation by demographic characteristics

In a paper examining the scope for targeting increased use of public transport through land use planning policies, Nurlaela & Curtis (2012) suggest that the influence of transport connectivity on location choice is informed by a person’s preferred mode, and individuals will select a property which supports their preferred mode. For example, if a person’s travel preference is to use public transport, they will locate in an area where this is provided for, and similarly if they prefer to use a car, they will locate where driving is unconstrained.

‘Transport connectivity’ in this context does not have a fixed meaning and alters depending on individuals’ preferences. Individual preferences show significant differences between age groups. A report by UWE Bristol Centre for Transport & Society (2018) found younger generations today are much less likely to hold a drivers licence compared to 30 years ago. In 1992, 48% of 17-20 year olds and 75% of 21-29 year olds held a driver’s licence. By 2014 this had fallen to 29% of 17-20 year olds and 63% of 21-29 year olds. The reasons stated in the report include the increasing costs of motoring and learning to drive, postponing of parenthood and living with parents longer, increased urbanisation, and increased participation in higher education.

This may present a barrier to attracting young people to rural areas given the largely car dependant nature of these areas.

Digital Connectivity

The importance of digital connectivity is a relatively recent phenomenon. However, there is a growing body of evidence which recognises the importance of digital infrastructure to the modern economy and society, and the consequential impact this can have on property prices.

Households

In a policy paper on digital connectivity, the Association of Directors of Environment, Economy, Planning & Transport (ADEPT) (2019) suggest that “digital infrastructure is now as important to our economy and society as traditional infrastructure and utility services”, that “good digital connectivity is a vital element of everyday life and has become increasingly important for ordinary activities”.

Lehtonen’s (2020) study into rural population changes in Finland concluded that “broadband availability is an increasingly important part of the critical infrastructure that impacts business and household location decisions”. In a study which analysed broadband availability and population data using difference-in-difference regression techniques, they showed that broadband availability reduced depopulation of remote and sparsely populated areas by 0.4% annually compared with alternative scenarios without broadband provision.

The UK’s Superfast Broadband State Aid Evaluation (2022), which examined the impacts of subsidised superfast broadband roll out to areas where this was not commercially viable, found that the roll out of superfast broadband between 2012 and 2019 resulted in a house price premium between 0.6 and 1.2%.

The evaluation’s review of the business and economic impacts of subsidised superfast broadband delivery also highlighted:

- an increase in the number of businesses located in the target area by around 0.5 percent.

- a 0.6% increase in employment and reduced unemployed claimants by 32 for every 10,000 premises upgraded.

- a 0.7% increase in hourly wages.

Given the predominantly rural nature of the target areas the report noted that “the programme may have encouraged the relocation of economic activity to rural areas” and enhanced their viability.

While there is limited evidence exploring the links between digital connectivity and household location choice, a 2019 study examining patterns of broadband speeds and property prices across urban and rural locations by Housesimple (2019) found that house prices in the UK were 24% lower on the streets with the slowest broadband speeds compared to the average for the postcode district.

A study of the impact of broadband availability and adoption on economic growth of rural areas in the US undertaken by Whitacre et al’s (2014) found that broadband adoption had a positive impact on employment and household income. Low levels of adoption led to a decline in employment and the number of firms. The study also found that broadband availability had limited impact, and concluded that future policy should be more demand orientated.

These findings highlight that improvements in digital connectivity could address lack of access to employment opportunities and concerns over pay, which were noted above as a key push factor in rural migration decisions.

Role of Digital Connectivity in Supporting Small Businesses

Serwicka & Swinney (2016) suggest a declining rural population can be exacerbated by business location choice as there is a circular relationship between business and household location choice. Businesses will locate where there are workers and customers, and households will locate where they are accessible employment opportunities and services.

Data on rural employment provided in section 'Rural Ways of Working' highlighted the role of micro-businesses and self-employment to rural employment structures. This section therefore examines the role of digital connectivity in supporting rural Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs).

While this is not strictly limited to household location decisions, these businesses usually move with their owners and the role digital infrastructure can play in supporting them is therefore discussed here.

In the context of a study drawing on a review of international literature and case study evidence from rural south-west Shropshire, Philip & Williams (2019) stressed the role of SMEs in rural employment, and identified three key sectors for SME activity in rural areas:

- Tourism and Leisure.

- Arts and creative industries.

With respect to farming, Philip & Williams (2019) note an increasing dependency on digital connectivity. Key requirements are:

- Access to information, including weather forecasts and price information.

- Farm governance requirements, including notification of livestock movements.

- Access to digital innovation, including data driven digital farming.

Tourism is said to increasingly depend on digital support before, during and after their visit:

- To enable online bookings.

- To enable holiday related and routine internet use during tourists’ stay.

Their study reported findings from the Rural Public Access Wi-Fi Services project (Rural PAWS) that tested the impact of deploying project-specific broadband services to remote rural households in order to examine personal and business-related behaviour. The study noted the following issues that compound the vulnerability of rural businesses in the two above sectors:

- Limited access, quoting secondary evidence that 10% of farmers in England and Wales did not have access to a computer in 2015.

- Poor digital infrastructure. Participants were disadvantaged not because they were not connected but because their digital connectivity did not adequately support their requirements.

- Lack of digital skills among farming communities.

- Personal motivation. Where individuals do not feel the need to improve their internet literacy, they tend not to be aware what the improvements offer to their business.

- Lack of options to move businesses rooted in immobile cultural and natural resources.

In conclusion of the trial, the paper highlighted the importance of fit-for-purpose digital infrastructure for rural household and business unit livelihoods, noting that over time this can address skills and attitudinal barriers. Improving the broadband quality for home-based rural businesses over the medium term led to improved internet competency through informal upskilling, creating a virtuous circle addressing a key barrier to internet use in some rural sectors.

The Scottish Government defines crofting as “a system of landholding, which is unique to Scotland, and is an integral part of life in the Highlands & Islands”.

Crofters are a small-scale landholder normally tenant landholders, who often use shared facilities including common grazings. Crofters often depend on mixed incomes substituting farming yields with other types of economic activities.

Digitally enabled initiatives such as the Croft IT, a project by Scottish Crofting Federation project can bring modern technologies such as advance soil monitoring and reduce the penalty of distance by creating communities of practice, providing opportunities for sharing knowledge and networking.

The project highlights opportunities for bringing self-employed communities together online, duplicating “Learning” aspects of agglomeration digitally.

Creative industries

Townsend et al (2014) assessed the role of broadband in the operation of rural businesses in a paper on the issue of economic and social sustainability of remote rural places across Scotland. The paper specifically investigates the importance of digital connectivity for SMEs, noting that rural areas in the UK attract newcomers who bring their businesses with them. Through a literature review and in-depth interviews predominantly with rural creative practitioners, they found good quality broadband had acted as a pull factor, removing the "penalty of distance” associated with being located in rural areas and expanding a practitioner’s network. 12 out of the 15 interviewees had relocated to rural areas and nine interviewees were located in remote or very remote rural areas in Aberdeenshire and the Highlands and Islands.

Digital connectivity was said to enable:

- Networking with peers and clients.

- Access to markets.

- Innovation, i.e. staying abreast of sector-relevant developments.

However, following their move connectivity was often found to be insufficient, had not been upgraded in line with urban areas, or was found to be too costly, eroding their competitiveness. As a consequence, businesses owners were struggling to survive, and some considered relocating again.

The paper suggests that a large divergence in digital connectivity from the standard provided in urban areas reduces the competitiveness and sustainability of rural areas and emphasises the importance of strong digital connectivity on retaining rural populations.

Summary of Key Points

Transport connectivity:

- Evidence of the importance of transport is mixed, with some evidence from house price stats and the evaluation of PT improvements showing that this can be distinguishing factor, if not a key motivation.

- While transport accessibility was found to impact, other factors including housing and neighbourhood attributes matter more.

- Transport is a derived demand, and hence often not explicitly stated as a location choice factor. However, it enables realisation of opportunities in connection with other choice factors.

- In rural areas maximum acceptable travel distances to key opportunities and amenities represent a constraint on household locations.

- Individual mode preference matters. Reduced car ownership and ability to drive, as well as car scepticism among young people may present a barrier to rural resettlement initiatives in this context.

Digital connectivity:

- Limited explicit exploration of the linkages between digital connectivity and household location choice found.

- Evidence from house price statistics suggests high quality digital connectivity adds to the attractiveness of residential locations, with high internet speeds commanding a house price premium.

- There is some evidence that digital connectivity improvements can increase the number of businesses, reduce unemployment, and increase pay, highlighting opportunities to address key rural migration push factors.

- A high proportion of rural employment is provided by SMEs. Digital connectivity is important to the vibrancy of key rural SME sectors, including the Creative sector, Farming and Tourism.

- Digital connectivity is a key pull factor for owners of creative businesses in the Highlands and Islands. However, in reality the quality of connection provided often falls short of securing competitiveness and this can be a barrier to retaining such businesses.

Rural farming and tourism SMEs tend to be immobile, tied to the location of natural resources. Digital plays a key role in supporting viability of these businesses. It enables access to customers and information, assists with business administration requirements and enables innovative production methods. The quality of digital connections often prevents digital technologies from optimally supporting these businesses. If provided, improvements in connection quality have been found to address other barriers, e.g. related to competency levels in the longer term.

To what extent are Digital Connectivity and Physical Mobility (i.e. transport) substitutable

While many academics believe the advances in technology and digital connectivity will impact transport operations (such as Connected Autonomous Vehicles and Mobility as a Service platforms), there is limited evidence this will substitute demand for transport. Innovate UK’s report on the UK Transport Vision for 2050 states “we expect to see an increase in the use of most travel modes” and digital connectivity will “create opportunities for greater efficiency, new services for travellers, and new business products and services”. Between the years 1994 and 2019, when availability and effectiveness of technology and digital connectivity rapidly increased, road traffic increased by 28% based on DfT (2022).

However, while digital connectivity is unlikely to replace demand for transport in the near future, this does not mean to say that it cannot play a role in improving connectivity where transport choices are limited.

In a report for the EU’s Improving Transport and Accessibility through new Communication Technologies (ITRACT) Salemink & Strijker (2015) state that, where increasing car ownership undermines demand thresholds for viable public transport and leaves those without a private car with fewer mobility options, connectivity can be facilitated by digital technology rather than physical mobility. “Digital connectivity can replace physical transport, whether by car or public transport”, providing opportunities to positively impact equality with people experiencing transport poverty now able to “become better connected and gain greater access to broader society”.

However, the report also highlights inequality risks associated with digital substitution, namely:

- Differential Information and Communications Technology (ICT) capabilities among highly public transport dependent groups causing the benefits to be skewed towards younger age groups, with potential risk of excluding older people without car access.

- Disadvantages to already excluded groups through reinforcing existing differences in financial resources, capabilities, aspirations, and social capital. These groups include older people with little ICT-related experience, low-skilled people, non-Western migrants, people in poverty, the visually impaired and physically impaired.

The report puts forward the importance of accounting for these risks by designing policies that equally consider the technological and social aspects when delivering ICT solutions.

Scope of Digital Connectivity Interventions

Brunori et al (2022) state that digitalisation has the potential to mitigate depopulation, social exclusion, and poverty in rural areas, but that it “should be intended as a means to an end, rather than the end itself”. In a SHERPA Discussion Paper they identify four factors of attractiveness of any place, which digitalisation is able to support within a rural setting:

- Quality of the rural environment: digital technologies can help promote rural areas as destinations and market their products. Digital technologies can also enhance tourists’ experience, for example through using virtual reality to create activities. Citizen science, i.e. the collection of data related to nature by the general public, can contribute to accumulation of knowledge and encourage participants to build identity.

- Quality of social relations: digital technologies can help overcome distance-related barriers to social relations.

- Quality of work: digital technologies mean people can work from home, reducing commuting.

- Quality of services: digital technologies enable e-commerce, online banking, home streaming and e-health and reduce the need for travel.

Therefore, in order to address rural depopulation, the applications of digitalisation in all four of these areas should be considered. The latter three are discussed in more detail in the following sections. Note that the first does not relate to the potential of digital connectivity to substitute transport and is therefore out of scope of this review.

It is noteworthy that the paper phrases these opportunities in terms of the contribution digital can make rather than substitution of transport interventions.

Access to Jobs and Home Working

Shrivastava (2012) suggests a number of ways in which ICT could make mobility in the UK more sustainable by reducing the need to travel. In this, home working and video conferencing were listed as growth areas. Homeworking has continued to increase since the publication of this report, and this was expedited by the pandemic. According to the World Economic Forum (2021), the pandemic led to a 20% increase in total internet usage and trends in remote working that are likely to persist. They also suggest that a work from home model “opens expansive opportunities for economic growth, global talent recruitment, job creation and, eventually, improved human prosperity and well-being”. They suggest many organisations will likely continue operating remotely to reduce real estate costs. The experience during COVID-19 provided evidence that in many sectors digital connectivity can at least partially substitute physical access to employment.

These trends are highly relevant in the context of rural depopulation. Remote communities across Scotland already experience relatively high levels of remote working as outlined in section 'Rural Ways of Working'. Leith & Sim (2022) note that “lack of career prospects” is a key factor in population decline in Scotland as a whole. In this context widening acceptance of home-based working demonstrates possibilities to attract members of the Scottish diaspora back to Scotland while working elsewhere.

In terms of the practicalities of substituting physical mobility with digital connectivity, Ye (2021) states that widespread digitalisation will need to overcome a number of issues including “lack of knowledge and capacity, high upfront capital costs, outdated regulatory models, lack of interoperable standards, the current semiconductor supply crunch, limited access to broadband, cybersecurity vulnerabilities, and concerns about compromised privacy and proprietary business information”.

There may also be difficulties changing attitudes to homeworking. Technology alone did not lead to a radical change in working from home practices, instead it took a significant global event which necessitated a change in attitudes to home working among employers and employees for it to become more accepted and widespread.

Prior to COVID-19, take up of home working was limited to a minority of employees even in areas with excellent broadband connectivity and in jobs where it was easily possible to work from home. Felstead & Reuschke (2020) report that the proportion of UK employees working from home was 5.7% of workers in January 2020, immediately prior to the onset of the pandemic. By April 2020, this increased to 43.1%.

However, the research also highlights that 88.2% of employees who worked from home during lockdown would like to continue doing so to some extent, with 47.5% wanting to do so often or all the time. This indicates sustained support for a greater role of digital connectivity in the work context.

From an employer’s perspective, there is some evidence that working from home increases employee productivity. In a UK study, Deole et al (2022) found that increased frequency in working from home is positively correlated with employees’ self-reported hourly productivity.

However, the benefits are dependent on employees’ circumstances. A cross-sectional study by Galanti et al (2021) found that family-work conflict, social isolation, and distracting environments at home all had a negative impact on productivity, and a systematic review of case studies by Hall et al (2022) found that homeworking increased work intensification, online presenteeism, and employment insecurity, resulting in psychological strain and poor levels of work engagement. The review noted that “homeworking as a choice is considered largely beneficial, but when homeworking is instead mandatory it is no longer deemed as advantageous and can have a negative impact on mental health”.

Productivity of home-workers varied with demographics and occupation. With respect to demographics, females, older employees, and people unmarried without children tending to be more productive.

Evidence on the variability of productivity benefits by industry highlighted that occupations in goods production and educational services experienced a drop in productivity. This is consistent with variability by sector found by research reported in Bertschek et al (2016) highlighted the risk of a “pronounced skills bias” where broadband adoption results in skilled workers in service sectors enjoying higher wages, employment rates and rises in productivity, but these same benefits are not experienced by lower skilled works in labour intensive or manufacturing sectors.

Evidence on the sectors and income groups where homeworking is most prevalent is provided by ONS (2023). Reviewing statistics on homeworking by sector, by salary, and by employment status leads to the following observations:

- The data confirms that digital substitution is more prevalent in professional, managerial, and administrative occupations, with homeworking only or hybrid working accounting for 64% of managerial and senior official occupations, 71% of professional, 61% of associate professional occupations, and 51% of administrative and secretarial occupations. In skilled trades, sales and customer services, caring and leisure, and other manual and elementary occupations, home and hybrid working accounted for 20% or less of employment.

- The scope for remote working substantially varied with salary, with home or hybrid working accounting for 13% of employees with salaries below £10,000 and 80% of employees with salaries of £50,000 or more.

- Homeworking was more common for the self-employed, with 32% of self-employed working exclusively from home compared with 14% of employees.

Access to Services

Wu et al (2022) studied the relationship between internet use and daily travel patterns using data from the Scottish Household Survey and the Integrated Multimedia City Data Survey. They found that “the increasing application of ICT in all aspects of daily life (e.g., teleshopping, telemedicine, and e-banking), which is brought about by technological evolution over time, enables and stimulates people to replace physical activities with virtual ones, particularly for those heavy ICT users dedicating a large share of their daily time budget to the Internet”. A discussion paper by Brunori et al (2022) supported this, stating that "digitalisation is rapidly changing some of the gaps in commercial services: e-commerce makes all types of commodities available in a few days. Home banking has already revolutionised the relation between citizens and their bank.” Shrivastava (2012) also identified synthetic environments such as online banking as a growth area in reducing the need to travel through ICT.

COVID-19 has substantially enhanced the evidence base on remote delivery of services including health and education. However, data analysed to date may be impacted by the pandemic and better understanding of the longer terms impacts is required to understand the scope for and enable planning for high quality remote delivery.

The Scottish Government’s Digital and Health Care Strategy (2021) emphasises the important role of digital technology in the future of healthcare, stating it can help address backlogs and increase capacity. Digital technology is expected to play a key role in embedding and sustaining health and social care integration. The strategy also recognised the shortcoming of digital reliance, namely the risk of digital exclusion and the need to ensure patients have a choice in how they access services.

A qualitative service evaluation undertaken by Schutz et al (2022) showed that the ability to substitute physical access to healthcare depends on the type of consultation. The study found that “there is an opportunity to have quick and stress-free [online] consultations as long as this is of a routine or follow-up nature. For more important treatment decisions and for some diagnostic consultations, patients in this study are clear that remote means are unlikely to be appropriate.”

In terms of the substitutability of education, a rapid evidence assessment by the Education Endowment Foundation (2020) found that “pupils can learn through remote teaching” and “teaching quality is more important than how lessons are delivered”. However, “ensuring access to technology is key, particularly for disadvantaged pupils”. The report also noted the importance of peer interaction to provide motivation and improve learning outcomes for pupils working remotely, and noted that pupils may require additional support to work independently. However, data analysis from ONS (2021) found that “remote learning was, at best, a partial substitute for in-class teaching during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, as pupils covered substantially less material when working from home than their peers in the classroom, according to teacher assessments.” The analysis also noted that teaching was more substitutable in primary school than in secondary school, and less substitutable for arts subjects. Remote learning may also increase inequalities, with a lower proportion of in-class learning material covered in schools with a higher proportion of pupils eligible for free school meals, and teachers at those schools also reporting a pupils’ learning being more dependent on parental instruction.

For university level education, an article by the World Economic Forum (2022) stated that although lecturers faced a “steep learning curve when adapting to new teaching technologies at the start of the pandemic”, in some cases online learning was actually more productive. However the article notes a digital divide among students, depending on their ability to access online platforms and services, and analysis by the ONS (2020) found that 29% of students reported being dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with their experience in the autumn term of 2020.

There may be geographical differences in substitutability of services. A report by Hirko et al (2020) examined a case study of a telehealth program implemented in rural Michigan in response to the pandemic. The report recognised the potential benefits of telehealth on rural communities by removing the need for travel and improving operational efficiencies. However, the report also noted that during the COVID-19 pandemic discrepancies in access speeds presented a challenge in delivering rural health care. Similarly, Steele & Lo (2013) reported that “remote and rural areas may often not have the bandwidth to support all types of telehealth applications”.

Access to Shopping

The potential for digitalisation to substitute physical mobility for shopping is noted by Brunori et al (2022) and Shrivastava (2012). However, based on data collected before the pandemic, there was limited evidence that this was occurring. Hesse (2002) hypothesised that “e-commerce is likely to reinforce longstanding trends of transport growth, rather than breaking them”. A study by Rohr & Fox (2014) found that although e-commerce can result in the removal of shopping trips and replacement with online purchases, it can also result in new and longer shopping trips such as making a specific trip for a specific item.

Research suggesting trip reductions in response to greater digital connectivity was limited before the pandemic is confirmed by data on trip purpose shares for journeys in Scotland from The Scottish Household Survey (2023). Little change was observed between 1999 and 2019, with the share of shopping rising only minimally from 22.7% of journeys in 1999 to 23.6% in 2019, despite the increasing prominence of e-commerce. It should be noted that average trip making remained largely unchanged. The mean number of trips per day recorded by the survey reduced minimally from 2 in 1999 to 1.9 in 2019. While the proportion of shopping trips increased temporarily during COVID-19, data for 2021 (23.7%) saw a return to 2019 levels. More recent data was not available at the time of writing.

However, digitalisation has the potential to narrow urban rural inequalities in accessibility to shopping. Evidence from a questionnaire undertaken in rural Wales by McHugh (2014) argues that “rural consumers use the internet to overcome any retailing limitation they feel present in their settlements”, although “rural residents do not complete more purchases online than urban residents, and respondents in both rural and urban settlements shop equally online and through brick-and-mortar retailing”.

However, there are barriers to substitutability of retail in rural areas. Analysis of customer complaints data reported in Citizens Advice Scotland (2012) highlighted that at least 1m Scots face surcharges, late delivery or refusals when trying to access goods online. Surcharges for consumers in the highlands and islands amounted to an average postcode penalty of nearly £15 and £19 per delivery, respectively.

Social interactions, leisure and entertainment

The potential for digitalisation to substitute physical mobility for entertainment is noted by Brunori et al (2022). However, a study by Rohr & Fox (2014) assessing the evidence of car traffic levels in Britain found that although “in some cases, online interactions might replace social interactions; alternatively, by widening an individual’s social network, this technology may be complementary with travel because social networking increases the ease of connecting with others.”

Summary of Key Points

- Based on increase in traffic levels between 1994 and 2019 there is little evidence that increased digital connectivity automatically results in trip substitution. However, there may be a role in enabling access to opportunities and wider society in contexts where transport connectivity is limited.

- Factors related to the distribution of connectivity and digital enablement may reinforce existing exclusion patterns, and equality impacts may need consideration.

- Digital infrastructure could mitigate depopulation by supplementing rather than substituting accessibility to jobs, services and social relations.

Work:

- During COVID-19 home working substituted physical commuting in many sectors, and many organisations are expected to retain this to cut costs.

- Attitudinal barriers need to be addressed; however the COVID-19 experience has helped in this regard, with 88.2% of workers who worked from home during lockdown would like to continue doing so.

- Widening acceptance of home-based working could address a lack of career prospects as a key driver of out-migration.

- Wider long-term adoption of home working requires addressing barriers in terms of knowledge and capacity, regulation, capital costs and cyber security.

- Scope for substitution varies by sector. Skilled jobs in service sectors and managerial occupations are likely to be more substitutable and lower skilled jobs in goods production less so. The self-employed are more likely to work from home exclusively.

- There is a strong correlation between substitutability and income group.

Services:

- Digital substitution in services is a key growth area, teleshopping, telemedicine and online banking are significant applications.

- Scope for digital substitution in service delivery varies by activity. In medical applications, routine and follow up consultations offer scope for substitution and more complex diagnostic consultations less so.

- On remote learning, ONS evidence suggests person to person contact was considered partially substitutable at best, more substitutable in primary than secondary and less so for arts subjects than sciences.

- Remote learning at universities was more productive in some cases, so long as barriers around lack of access to digital platforms were overcome.

- The evidence highlighted substantial equality issues that need consideration.

- Shopping and socialising:

- There is limited evidence that increased uptake of e-commerce opportunities reduced shopping trips, although it may help overcome some gaps in the provision of traditional retailing in rural areas.

- Deliveries to remote communities can be refused or face substantial surcharges.

- There is some evidence of substitutability with respect to social interactions. However, there is also some evidence that social networking online is complements rather than substitutes transport.

To what extent do the above variables impact on depopulation occurring within communities?

This section of the literature review will discuss digital intervention in the context of rural migration, including consideration to the scope for substitution and unintended consequences.

Addressing Rural Shortfalls in Transport Connectivity

Highlands and Islands Enterprise (2022) research has explored a range of topics related to life in the Highlands and Islands. The research collected views from over 5,000 adults living in the Highlands and Islands. Respondents were asked what things are needed for their community to thrive. While the survey did not directly investigate depopulation, the ability of rural communities to thrive is closely linked. Improved local transport connections were cited by 15% of respondents, and improved transport connections between my local area and other parts of Scotland selected by 16%. 20% quoted improved broadband, and 11% said improved mobile phone coverage was a priority. By comparison 47% said housing for local families was needed for the community to thrive, followed by more job opportunities (32%), and local businesses and trades (24%).

Porter & Turner (2019) found for young people education and skills development opportunities are typically focused on urban centres, which “restricts opportunities for skills development and the take-up of learning and training opportunities in more remote rural areas”. They state that “Transport and travel are likely to play a crucial ‘cause and effect’ role in exacerbating poor skills and low productivity, especially in contexts where transport density is low and subsidised transport is unavailable”.

The importance of transport in addressing rural depopulation challenges is also confirmed by Skerratt (2018) in a report prepared for the Prince’s Countryside Trust. Based on surveys of over 3,000 respondents in England, Scotland and Wales, the research identified that poor broadband and mobile coverage, poor road and transport networks, and a poor variety of employment opportunities are the top three barriers facing remote rural communities and links these barriers to the out-migration of young people.

Based on 2020 data from the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) reported in the Scottish Government publication Rural Scotland Key Facts 2021 public transport accessibility to key services is a key challenge in remote rural areas:

- only 40% lived within a 15-minute public transport journey from the nearest GP (compared with 92% in non-rural Scotland).

- 63% lived within a 15-minutes journey from the nearest Post Office (compared with 96% in non-rural Scotland).

- 29% within a 15-minute public transport journey to the nearest shopping facility (compared with 81% in non-rural Scotland.

This is reflected in the findings of Scottish Government (2010), which lists Transport as a ‘push’ factor for young people moving out of rural areas stating “insufficient public transport adds to feelings of social and economic isolation”. Specific concerns around public transport are centred on the high cost and lack of connectivity it offers to rural jobs, which is “reported to restrict young people’s employment choices” both from the employee’s point of view and employers who may be “put off employing young people with particularly poor public transport connections”. Among those who are economically active the same report states a shortage of public transport links, and high transport costs where they do exist, were found in a range of studies in Orkney and the Outer Hebrides to restrict residents access to job opportunities and important services.

The continued relevance of transport challenges faced by rural communities is confirmed by a survey of 5,301 adults conducted by Ipsos on behalf of Highlands and Islands Enterprise (2022) (HIE). The survey reviewed respondents’ satisfaction with the reliability, frequency, and cost of transport services. Table 2‑6 below shows satisfaction scores statistics by mode of transport. Bus scored highest on reliability when compared with rail and ferry, and ferry scored highest with respect to frequency. Cost emerges as a key concern, with 52% of rail, 36% of ferry, and 24% of bus passengers stating that they were dissatisfied with the cost of travel. This is consistent with the Scottish Government (2010) finding that high cost of public transport is a push factor for rural migration.

|

Category |

Rail |

Bus |

Ferry |

|

The reliability of the service |

19% [25%] |

30% [22%] |

11% [34%] |

|

The frequency of the service |

18% [25%] |