Perceptions of and issues with bus use

General Perceptions of Bus Use

Across both the baseline and follow-up surveys, respondents were asked to rate the extent to which they agreed with a series of statements related to buses and bus use. Table 11 outlines the proportions of respondents that agreed with each statement and highlights the changes in attitudes. This shows that two thirds (67%) of respondents in the follow-up survey agreed that buses were environmentally friendly (an increase of eight percentage points), while 54% agreed that buses were affordable (an increase of 25 percentage points - and representing the biggest change across all perceptions). There were improvements in most of the elements that respondents were asked about, as well as a reduction in the proportions concerned about the spread of viruses on-board buses. There were, however, also slight increases in the proportions of respondents who agreed that buses were too busy/crowded and that there was lots of anti-social behaviour on buses.

| Agree/Strongly Agree | Before Scheme | After Scheme | Percentage Point Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buses are environmentally friendly | 59% | 67% | +8% |

| Buses are affordable | 29% | 54% | +25% |

| Bus travel helps to make the roads safer | 50% | 53% | +3% |

| Buses are clean and comfortable | 44% | 52% | +8% |

| Current bus routes meet my/their needs | 47% | 51% | +4% |

| Buses are too busy/crowded | 45% | 47% | +2% |

| There's lots of anti-social behaviour on buses | 39% | 45% | +6% |

| Buses are a fast and convenient way to travel | 40% | 45% | +5% |

| Worried about viruses spreading on buses | 54% | 24% | -30% |

Issues Experienced with Bus Use

Respondents in both the baseline and follow-up surveys were asked to identify any issues they/their child experienced in using the bus. Table 12 outlines the results and shows that cost was no longer the main issue following the introduction of the Young Persons’ Free Bus Travel Scheme. Again, this represents the largest change, with a reduction of 31 percentage points in those who reported cost as an issue.

| Issue | Baseline | Follow-Up | Percentage Point Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buses are not reliable/on time | 37% | 49% | +12% |

| The bus doesn't run often enough | 35% | 45% | +10% |

| Timetables are not suitable | 27% | 38% | +11% |

| The bus takes too long | 36% | 35% | -1% |

| Safety concerns at night | 45% | 34% | -11% |

| Safety concerns when travelling alone | 38% | 32% | -6% |

| Buses don't go where need/want | 28% | 29% | +1% |

| Too young/not confident to use on own | 29% | 28% | -1% |

| Parent/carer decides on travel | 24% | 23% | -1% |

| Have to rely on family when travelling | 27% | 20% | -7% |

| Cost | 51% | 20% | -31% |

| There's no bus stop nearby | 12% | 12% | - |

| Don't know about services/how to pay | 20% | 11% | -9% |

| Other | 3% | 3% | - |

| Accessibility issues | 2% | 1% | -1% |

| Total Respondents (n) | 16,616 | 10,417 | - |

The proportions of respondents highlighting safety, knowledge about services/how to pay, and having to rely on family when travelling as barriers had also reduced.

Based on the follow-up survey findings, the main issues experienced since the introduction of the scheme were reliability or buses not turning up on time (noted by 49% of respondents), and that buses did not run often enough (identified by 45% of respondents). There was also an increase in those experiencing challenges related to service provision, including reliability, unsuitable timetables and lack of frequency.

Those who indicated ‘other’ challenges (3%), identified a wide range of issues. These included anti-social behaviour; buses being too crowded/busy; young people with a disability, ASN or anxiety found using the bus difficult; a lack of direct routes; journeys that took too long; no bus services available nearby; the cost for adults to travel with their children; limited services, particularly in the at night and at the weekend; inability to take bikes on-board; poor cleanliness and comfort; and difficulties in obtaining the free travel card.

Similarly, many eligible non-users within the focus groups also highlighted that they faced issues in relation to a lack of accessible, reliable services which went where they wanted/needed and didn’t experience excessively long journey times. It was suggested that improvements were needed to bus services in order to make the scheme more accessible and attractive for young people in certain areas. In particular, some areas were said to be lacking any services, while others called for greater reliability, greater frequency, alternative routes, and shorter journey times to be made available.

Several non-user survey respondents and focus group participants also noted they would need to drive to a bus stop as there was nothing accessible locally, but there were no parking facilities available. While some felt that they might as well drive for their full journey, others suggested that locating parking provision near bus stops along key routes, or main bus interchange locations, may encourage more young people to use the Young Persons’ Free Bus Travel Scheme:

“Having parking near bus stops… When I drive back over to [transport hub] you can get a bus to pretty much anywhere from there, it’s so handy… but you can’t just park and ride.” (Eligible Non-User)

Perceived Safety of Public Transport

As noted in Table 12 above, safety concerns when travelling at night and alone were explored, with both issues having improved since the introduction of the Young Persons’ Free Bus Travel Scheme. ‘Safety concerns at night’ showed an 11 percentage point reduction between the baseline and follow-up surveys, while ‘safety concerns when travelling alone’ showed a six percentage point reduction.

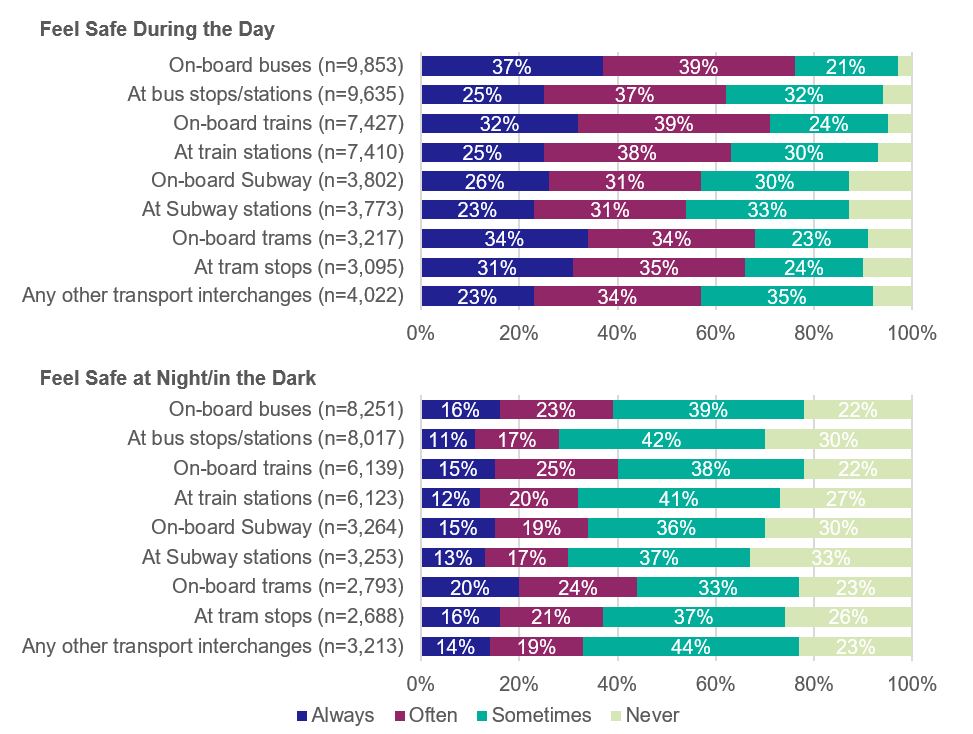

In order to more fully understand any impact that the Young Persons’ Free Bus Travel Scheme may have had on perceptions of safety, respondents to the follow-up survey were also asked to indicate the extent to which they/their child felt safe using different forms of public transport during the day and at night/in the dark. Different modes were covered to provide context of perceived safety across the public transport spectrum.

Figure 15 shows that young people felt safer more often during the day compared to at night/in the dark across all modes. This was consistent with the baseline survey, where respondents were asked to consider how safe they felt using the bus during the day and at night/in the dark (82% felt they were either always or often safe during the day compared to 37% at night/in the dark).

When considering bus use only, comparison of the baseline and follow-up survey suggests a reduction in users sense of safety during the day, falling from 82% of respondents in the baseline who felt they were either always or often safe during the day, to 76% in the follow-up survey. Conversely, there was a slight improvement in the proportions who felt safe using the bus at night, rising from 37% who felt always or often safe in the baseline, to 39% in the follow-up survey. While this is not as extensive as the 11 percentage point reduction in the proportion of respondents who experienced issues with safety concerns at night (noted at Table 12 above) the combined results suggest an improving situation in this respect.

Comparing buses and other public transport modes rated in the follow-up survey shows that respondents felt safer on buses than any other modes of public transport during the day (76% felt safe on-board buses either always or often during the day). While safety at bus stops/stations ranked third (behind tram and train stops/stations) there was little difference between these (at 66% for tram stops and 62% for bus stops/stations).

When travelling at night, those using trams tended to feel safest on-board (with 44% feeling safe either always or often), with buses ranking third. Respondents felt least safe regularly at bus stops/stations, with 28% indicating they always or often felt safe at bus stops/stations at night/in the dark compared to 37% who felt this way about tram stops.

When the data was compared by demographic group, the following results were observed:

- Gender: across all modes of public transport (both on-board and at stops/stations and interchanges), males were more likely to say they always felt safe compared to females and trans, non-binary and other those who identified as another gender. Meanwhile females and trans, non-binary and other those who identified as another gender were more likely to say they sometimes felt safe compared to males.

- Sexual Orientation (aged 16+ only): results were highly variable, although in general, straight/heterosexual respondents were more likely to say they often or never felt safe, while LGB+ (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and those identifying as having an ‘other’ sexual orientation) respondents were more likely to say they sometimes felt safe. However, LGB+ respondents were more likely to say they never felt safe when using buses at night.

- Disability: for travel during the day, respondents who indicated they had a disability were less likely to say they always and often felt safe and more likely to say they sometimes or never felt safe compared to those without a disability. At night, however, disabled respondents were less likely to say they always and often felt safe, and more likely to say they never felt compared to those without a disability, while there was often little difference in the proportions who sometimes felt safe.

- Ethnicity: when using buses, trains the Subway, and other transport interchanges during the day and at night, respondents from ethnic minority backgrounds were more likely to say they always felt safe compared to those from white ethnic groups.

The reasons given for not always feeling safe while using the bus and other modes of public transport were largely consistent, although concern was often more acute when travelling alone and/or at night. Key issues included:

- Anti-social or rowdy behaviour, including swearing, loud music, vaping, spitting, fights, vandalism, etc.;

- Intoxicated people (i.e. alcohol and/or drugs);

- Inappropriate behaviour/attention from other passengers (both groups of young people (often described as teenagers, youths or gangs) and adults (often men));

- The perceived risk of children mixing with strangers and unknown adults;

- Age of the young person - it was felt inappropriate for young children to travel unaccompanied, particularly at night;

- Witnessing or being personally subjected to bullying or harassment (or concerned about being a target of this), including sexual, racial, homophobic (or other LGBTQ) harassment, or due to religion/belief;

- Busyness and crowding/overcrowding of services being intimidating for children and young people;

- Physical safety when service was busy (e.g. having to stand in a moving vehicle) and lack of seatbelts;

- Young people with disabilities and ASN also indicated that their condition led to them feeling less safe, less able to cope with public transport, or were concerned that it could make them a target for bullying/discrimination;

- Lack of (visible or accessible) staff, policing or security - this was more of an issue for trains, the subway, trams and other transport interchanges compared to buses; and

- Poor lighting, especially at stops and stations.

Focus Group Perceptions of Safety

Focus group participants also discussed their perception of safety using buses compared to other modes of public transport, with mixed responses.

For some, the train was considered safer than bus use (although some did indicate this depended on the route, time of day/night, and any events that may be happening). It was noted that the ban on alcohol was enforced on trains, that a conductor was typically available to monitor behaviour, there was generally more space on trains so passengers could move seat or carriage if necessary, and that the British Transport Police would arrive quickly if needed:

“I think it’s worse on the buses. On the train, there’s the conductor and police at the stations and stuff, and they’re always on hand if anything does go wrong, and on the whole I think it’s definitely a lot calmer on a train.” (Scheme User)

Similarly, two participants felt there was less anti-social behaviour, as well as less littering and greater levels of cleanliness on trams compared to buses. They posited a direct link between the age of passengers on the bus compared to trams, with trams typically being used by fewer young people and more working age people.

Conversely, some parents/carers and young people themselves felt safer on-board buses compared to other types of public transport or using active modes. Generally these respondents were reassured by the use of CCTV on-board buses, as well as the proximity and accessibility of the driver and presence of other passengers due to an expectation that they would assist if required:

“In general, they [parents] think the buses are safe, and I think so too, because they’re all CCTV’d and stuff.” (Eligible Non-User)

“I would say to my kids if they were going to be traveling on their own to sit downstairs so that they have the driver there if they needed help, but also other passengers can stick up for each other. I’m sure someone would intervene if my kids had any trouble on the bus. Whereas the train, you can be in a completely empty carriage at times... So, overall, I’d feel safer with them on the bus rather than on the train.” (Parent/Carer of Scheme User)

“I find that on the train, at night there’s a lot more creepy people and anti-social behaviour because you don’t feel like you’re being watched as much, whereas on the bus it’s a smaller area and you’re quite close to the driver so you could say something, but on a train you’re just in empty carriages with some drunk guy trying to hit on you.” (Eligible Non-User)

More specifically, several young people suggested they would prefer to use the bus at night as they felt this was safer than other options (often compared to walking alone in the dark):

“I’m much more likely to take the bus in the evenings when I have the free bus pass because I guess that’s safer when my university finishes, often at 9 or 10 [pm] and especially in the winter… I usually take the bus. Even if it’s empty, I just feel safer than walking.” (Scheme User)

Young women in particular noted that they felt that taking the bus at night would be a safer option. Some were again reassured by the presence and accessibility of the driver, while others suggested that the Young Persons’ Free Bus Travel Scheme had reduced the stress of travelling alone or worrying about how friends would be able to get home safely at night. Girls and young women could now either travel home together in a group, or were reassured that individuals were not travelling alone. This was said to make them more inclined to pursue night-time social opportunities:

“I think the latest I’d ever want to stay out if I was travelling on the bus would be, like, 10pm because I don’t like being out when it’s dark. But that’s nothing to do with the bus, that’s just my personal preference. And I would feel safer on the bus than if I wasn’t on the bus, because I know that there’s other people on the bus whose job it is to make sure that the passengers are safe.” (Scheme User)

“I would only go out with my family before. I wouldn’t go out with my friends because I’d be worried about how we would get there, how we’d get back, would I be safe… but because everybody has the free bus pass then you know that you’ll be together and you won’t be split up to get home. So, it feels a lot more safe so I feel more inclined to go out.” (Scheme User)

Anti-Social Behaviour, Bullying & Discrimination

In addition to exploring general safety perceptions, both the follow-up survey and focus groups sought feedback on respondents’ experiences of anti-social behaviour, bullying and discrimination when using buses and other modes of public transport within the last 12 months. It should be noted, however, that no official statistics related to anti-social behaviour on board buses were available for inclusion within this evaluation. Bus operator data detailing instances of anti-social behaviour before and after the introduction of the Young Persons’ Free Bus Travel Scheme was either unavailable or considered commercially sensitive, while official national statistics either do not adequately identify anti-social behaviour within a distinct category, or do not identify anti-social behaviour on transport/buses. As such, the findings presented in this section rely solely on perceptions and anecdotal evidence provided by survey and focus group respondents. This was based on their experiences and personal interpretation of what constituted anti-social behaviour, as well as being informed by respondents own levels of tolerance in relation to what they considered acceptable/anti-social.

As shown in Table 11 above, when survey respondents were asked whether they agreed there was ‘lots of anti-social behaviour’ on buses, there was a six percentage point increase from the baseline to the follow-up survey. However, as also discussed above (Table 12) when asked to identify issues experienced when using buses, concerns related to safety showed decreases both when travelling alone and at night from the baseline to the follow-up survey (a six percentage point reduction and an 11 percentage point reduction respectively).

In addition to the questions noted above, a new question focused on specific experiences of anti-social behaviour was asked in the follow-up survey. Overall, 54% of follow-up survey respondents indicated that either they/their child or their friends or family had seen or experienced anti-social behaviour when using any form of public transport in the last 12 months. Respondents were also asked a similar question in relation to bullying and discrimination, and while this issue had been included in the baseline survey, question wording differed between the two surveys. Overall, 14% of follow-up survey respondents had seen or experienced bullying or discrimination when using any form of public transport in the last 12 months, compared to 18% of respondents in the baseline survey that had experienced bullying and discrimination on board buses at some point.

The vast majority of instances of anti-social behaviour, and bullying and discrimination, were experienced on buses. However, as the survey was targeted at bus users it is to be expected that respondents would be more likely to experience issues on this mode. Experiences on other modes of public transport were likely to be underrepresented due to limited usage. Much higher proportions of respondents travelled by bus for each journey purpose (between 33%-57%) compared to all other public transport modes (where up to 11% used trains and up to just 2% used the Subway, trams or ferries).

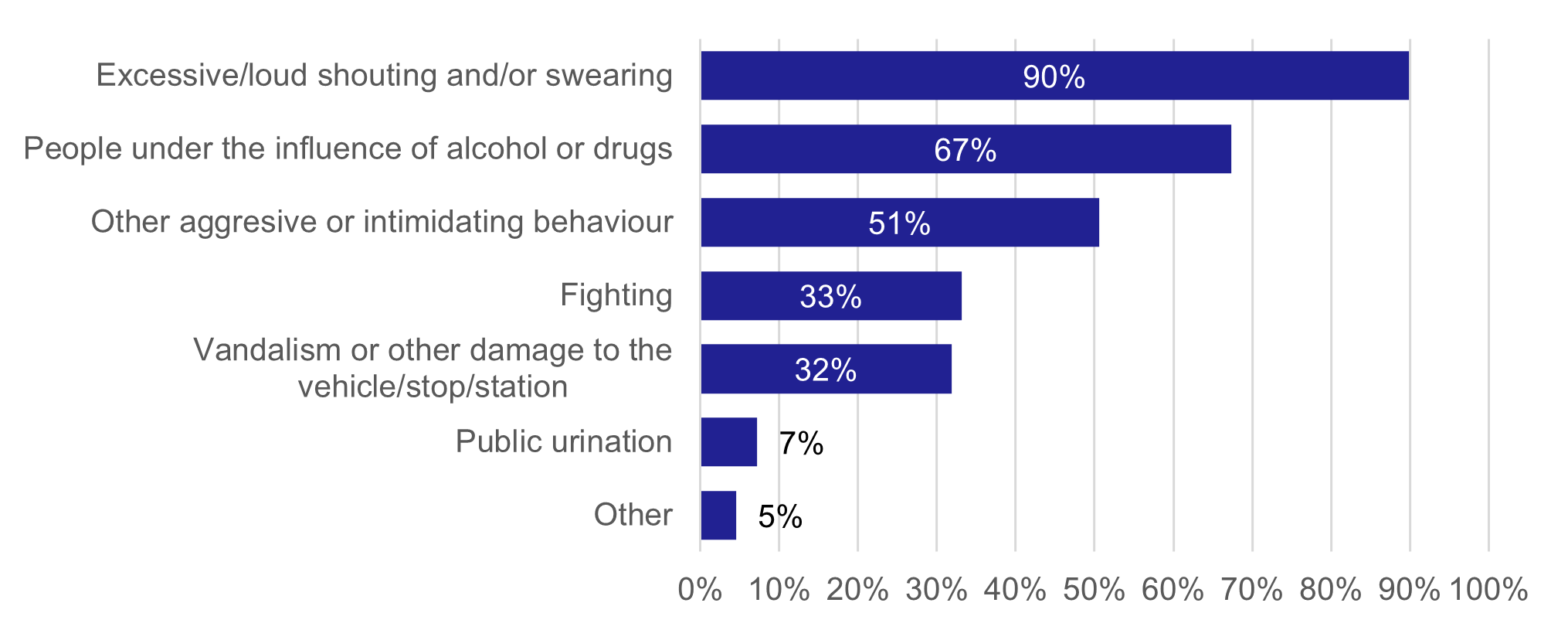

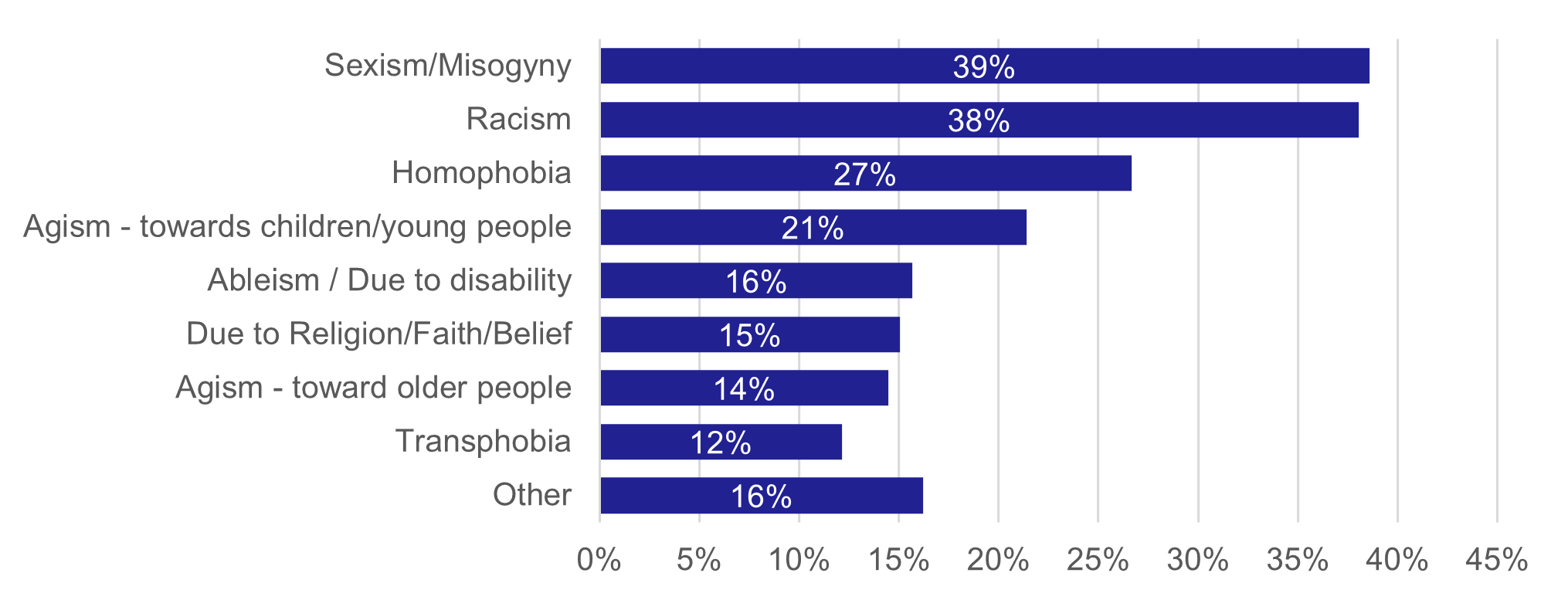

Figure 16 outlines the extent to which various types of anti-social behaviour were experienced by survey respondents, while Figure 17 details the types of bullying and discrimination that were experienced.

Shouting and swearing, people being under the influence of alcohol or drugs, and other aggressive or intimidating behaviour were the anti-social behaviour issues most often experienced by follow-up survey respondents. While the baseline survey did not explore instances of anti-social behaviour specifically, it was raised by respondents in their qualitative comments as one of the main reasons for not feeling safe on-board buses. Where the nature of such anti-social behaviour was outlined, this was largely consistent with the experiences of follow-up survey respondents.

Meanwhile, among follow-up survey respondents, the most commonly experienced types of bullying and discrimination were sexism/misogyny and racism. The next most common issues were homophobia and agism towards children and young people. Other types of bullying and discrimination included people being targeted due to their appearance, including weight and height, body image/shaming, the way they dressed, hair colour or style, facial features, makeup styles, and wearing glasses. A few also noted they had been targeted because of where they came from (e.g. out of town, England, etc.). General bullying and aggressive behaviour were also described, with other children/young people often said to be the perpetrators, although some adults were also said to exhibit such behaviours. Again, results were largely consistent with those in the baseline survey, where bullying and discrimination was largely linked to a person’s appearance and/or protected characteristics.

Focus Group Experiences

All focus group participants were asked about experiences of anti-social behaviour, bullying or discrimination while using buses. While a few participants, typically less frequent bus users, and those who travelled at less busy times, indicated that they had not witnessed or experienced this, most did outline concerns and personal experiences. While many of the discussions focused on aspects of anti-social behaviour, a few female respondents did identify instances of sexual harassment, including being stared at by older men, being groped, and verbal sexual abuse.

In terms of anti-social behaviour, it was suggested this was usually (although not exclusively) perpetrated by young people. The most common instances/concerns discussed included young people being loud and disruptive on buses, and arguing with the driver or other passengers, as well as drunk people (typically adults) on buses and at bus stops/stations:

“Quite often, there’ll be people, often my own age, being anti-social. Like, I’ve had people on the bus that have been playing things on their phones really loud and then when older people ask them if they’ll turn it down, they’ll have really rude replies. Or there’ll be people smoking and vaping on the buses with the windows closed, and when [other] people open the windows, they’ll have rude things to say about it. It’s just sometimes not a nice place to be, on the bus.” (Scheme User)

“I’ve seen people shouting and swearing at each other and stuff, more in [city] and stuff, it’s young people causing issues… You see the odd argument here and there… I probably wouldn’t get involved, because it’s my safety at risk.” (Scheme User)

There was also a sense that such behaviour was happening around buses as a result of the Young Persons’ Free Bus Travel Scheme as many of the young people would not have been using the bus otherwise:

“My daughter and I were on a bus in [city] one afternoon, and at one of the stops there was a very large group of young people with their passes who got onto the bus. They were being rude to the driver straight away and then they went upstairs and started stomping and being rude until the driver stopped the bus… and made them all get off. They were all very abusive to the driver when they got off, and I suppose it did make me think, I don’t think these kids would have been getting onto buses if it wasn’t for the passes - so that maybe is a downside.” (Parent/Carer of Scheme User)

Parents and young people expressed some concerns about the lack of official interventions and inconsistent responses from bus drivers when dealing with anti-social behaviour:

“Sometimes the drivers don’t actually know about it [anti-social behaviour] or, if they do, they won’t really do anything about it. They’ll just let the passengers deal with it.” (Young Person)

“My children were waiting at a bus stop in [city] where there were older kids hanging around and just generally being a nuisance, and when the bus driver pulled up he literally refused to let all the kids on, regardless of if they were in that group or not… they were then left waiting for over an hour and I eventually went and picked them up.” (Parent/Carer of Scheme User)

Conversely, other parents, typically those living in island and remote rural communities were more likely to say that drivers were helpful and flexible in meeting their needs, giving them confidence and greater peace of mind in relation to their child using the bus independently:

“The drivers, because it’s aways the same kids getting on and off all the time, even though we don’t live right at the bus stop, the driver knows where the house is and so he would look out for them in the mornings if it was chucking it down with rain. Sometimes, the driver would wait on a school day, knowing they were coming out, so it’s been really positive for us.” (Parent/Carer of Scheme User)

“We live in a rural area and usually the drivers are quite friendly and helpful, and even make additional stops sometimes, so we’ve never had any issues.” (Parent/Carer of Scheme User)

Further, as outlined above, not all focus group participants had experienced instances of anti-social behaviour, with some stressing that not all young people were rude or troublesome while travelling by bus. A few also stated that they tried to remember that they were young once as well and tried not to judge young people’s behaviour overly harshly:

“I try to remember that I was 13 to 14 years old at one time, and I was probably cheeky as well… It is nice to see youthful energy on the buses. And it is fair to say that not all the kids are rowdy or are looking to cause trouble… and to have a busy bus I suppose, because during Covid there were only three or four people on them sometimes, so it is nice to see the bus a bit busier I suppose.” (Other Bus User)

Others also stressed that anti-social behaviour was not limited to buses, and suggested that they had either witnessed or experienced similar issues while travelling on other modes of public transport:

“I have experienced extremely drunk people on the trains.” (Other Bus User)

“We’ve only got really one train service… and that can be really really crowded and used as a party train, so the buses are sometimes preferable.” (Other Bus User)

“I get the Subway for the football, and I suppose that can be pretty raucous. I don’t feel it because I’m part of that crowd, but if you’re not part of that crowd it must feel very anti-social.” (Other Bus User)

Distribution of Anti-Social Behaviour

In addition to perceptions or experiences of anti-social behaviour on and around buses, there was also a perception across a few respondents (to both the follow-up survey and focus groups) that the Young Persons’ Free Bus Travel Scheme may have introduced instances of anti-social behaviour into new areas due to the ability for young people to travel and congregate in new/different places:

“Now that young persons have free bus passes, they’re being used and abused by teenagers travelling to previously inaccessible areas of the city (for them) and causing disruption, vandalism and general nuisance behaviour.” (Follow-up survey)

“I live near the beach and all the way through the hot weather the buses were full of kids coming from across the areas going to the beach, and we’ve had a lot of anti-social behaviour down here with gang fights and stuff, and it’s really been quite horrible - because they’re facilitated to move around… it is intimidating… There are many, many more kids from out of area, far out of the area travelling down to where we are out of hours.” (Other Bus User)

It should be noted, however, that without robust data on instances and locations of anti-social behaviour, it cannot be determined whether such examples represent truly ‘new’ instances and increasing levels of anti-social behaviour overall, or if anti-social behaviour has been displaced, moving from one area to another.

Conclusion

As outlined above, data on the number of instances or rates of anti-social behaviour on-board buses or other forms of public transport was not readily available. However, the findings suggest that, while the types of anti-social behaviour have not necessarily changed since the baseline survey, there was a perception among some respondents that this problem had become worse/more frequent on and around buses since the introduction of the Young Persons’ Free Bus Travel Scheme. Indeed, there was a six percentage point increase in the perception that ‘there’s lots of anti-social behaviour on buses’ between the baseline and follow-up survey (shown in Table 11). Professional stakeholders (including bus operators and local authorities) also perceived there to have been a rise in anti-social behaviour related to bus use (see the Stakeholder Feedback Report).

Considering the above results alongside Police Scotland Management Information Force Reports, which shows that the total number of anti-social behaviour incidents reported to them nationally had declined by around a third between 2020/21 and 2022/2023, it may be that anti-social behaviour on-board buses is not being reported and recorded in official statistics.

Without access to robust standardised recording practices and statistical data which spans pre- and post-implementation periods, however, it is not possible for this research to say with certainty whether instances of anti-social behaviour have truly increased, decreased, or remained relatively static overall since the introduction of the Young Persons’ Free Bus Travel Scheme.

Similarly, it cannot be determined whether anti-social behaviour had moved away from some areas and onto buses and/or into newly accessible areas. When considering safety concerns and the issue of anti-social behaviour on buses, it is also important to note that some respondents perceived buses to be safer than alternative options, particularly when travelling at night. In addition to the qualitative comments showing that both young people and their parents/carers were reassured on buses by the use of CCTV, access to the driver, and the presence of other passengers, Table 12 showed an 11 percentage point decrease in respondents having safety concerns when travelling by bus at night, and a six percentage point decrease in safety concerns when travelling alone. As such, the Young Persons’ Free Bus Travel Scheme appears to have brought perceived positive safety impacts as well as increased levels of concern over anti-social behaviour.