2. Current situation and our approach to change

2.1 Current car use behaviour

According to Scottish Transport Statistics 2020, cars make up over 75 per cent of total traffic volumes on the roads in Scotland, and the majority of all journeys in Scotland are made by car. In 2019, 65 per cent of journeys were made as a car driver or passenger. This proportion has been growing over time, as has overall car kilometres driven. Between 2009 and 2019, the number of car kilometres driven in Scotland increased by 7 per cent, despite the population only increasing by around 4.5 per cent (Mid-2020 Population Estimates Scotland). The proportion of car journeys made with only one person in the car has also grown over time.

It is important to recognise that a small number of longer journeys account for a disproportionate percentage of total car kilometres, with around 4 per cent of trips (those over 55 kilometres) accounting for nearly 30 per cent of the total kilometres driven in 2019. Conversely, despite 45 per cent of trips being under 8 kilometres in length, these accounted for just 12 per cent of trips of total car kilometres in 2019 (Internal analysis on Scottish Household Survey, 2019 reported in Transport and Travel in Scotland 2019). The most common trip purposes by car or van in 2019 were for commuting (28 per cent); shopping (23 per cent); and leisure (19 per cent), with 4 per cent being for education, 3 per cent for business, 1 per cent for holidays and 21 per cent for other purposes (Ibid). These proportions have been relatively stable over the years preceding the pandemic. Of employed adults in Scotland, 68 per cent travelled to work by car in 2019, while in rural areas this figure was over 80 per cent (Scottish Household Survey, 2019 reported in Transport and Travel in Scotland 2019, Table 1).

People living in rural areas are more likely to have access to and use a car, and use it more frequently. In remote rural areas in 2019 over 70 per cent of people aged over 17 drove at least three times per week, compared to only 46 per cent of people living in large urban areas (Scottish Household Survey, 2019 reported in Transport and Travel in Scotland 2019, Table 5). This can partly be explained by poorer access to frequent and reliable public transport in rural areas, with analysis showing that 84 per cent of rural areas have the lowest level of access to bus services (Scottish Household Survey, 2019, reported in Scottish Transport Statistics no.39, 2020). Yet, while access to cars is higher in rural than urban areas it is by no means universal, with lower income rural households being significantly less likely to have access to a car than higher income rural households. As outlined previously, inequality in access to private cars also extends beyond income, with younger people, older people, women, disabled people and non-white Scottish or British ethnic groups all less likely to have access to a car than the general population (Scottish Household Survey, 2019, reported in Scottish Transport Statistics no.39, 2020).

As well as an inequalities in access to cars, we know that car kilometres are not equally distributed across Scotland’s local authority areas, with car kilometres per head of population being lower in urban local authority areas than in rural local authority areas (National statistics. Road traffic estimates in Great Britain: 2020). For example, while Glasgow is home to 12 per cent of Scotland population only 7.6 per cent of the total car kilometres driven in Scotland are within the Glasgow local authority area, in contrast with the Highland local authority area, where 6 per cent of Scotland’s total car kilometres are driven, despite it being home to just 4 per cent of the country’s population. It is however acknowledged that not all driving that occurs on rural roads should be classified as ‘rural trips’, with journey origin and destination data showing that approximately 30 per cent of the total distance travelled comes from trips that both start and end in urban areas, rising to 40 per cent if trips that both start and end in accessible small towns are included as well. Additional data tables and charts can be found in the route map annex.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has created an unprecedented effect on transport and travel in Scotland, with journeys to work particularly affected by temporary workplace closures, car traffic on trunk roads is now close to pre-pandemic levels (Transport Scotland. COVID-19 – Trends in transport and travel in Scotland during the first year of the pandemic). The current direction of travel is towards more car kilometres being driven each year, rather than fewer. Reducing car kilometres by 20 per cent by 2030 will not be possible just by focussing on the shortest journeys or commutes to work where it is easier for people to switch to active travel or public transport, but requires a more holistic approach that also supports people to travel less, switch to more local destinations and reduce single occupancy trips wherever possible.

2.1.2 Opportunities for change

Despite current data showing high levels of car use, public opinion surveys tell us that there is public support for change. In a recent survey, 73 per cent of respondents agreed that ‘for the sake of the environment, everyone should reduce how much they use their cars’, whilst 43 per cent agreed that they were ‘willing to reduce the amount [they] travel by car to help reduce the impact of climate change’ (Department for Transport. National Travel Attitudes Survey: Wave 02, January 2020. Table NTAS02021e).

This mirrors the support shown in the latest report from Scotland’s Climate Assembly, in which 91 per cent of its members, selected to be broadly representative of the population, agreed with the recommendation that we need to ‘provide education for all to support the transition from car use to public and active transport so people recognise the climate impacts and change behaviours willingly’, in order to tackle the climate emergency in an effective and fair way (Scotland’s Climate Assembly: Recommendations for Action Report. Scotland’s Climate Assembly, June 2021). The Climate Assembly also noted that its members support a range of actions to enable a reduction in car use, including ‘improvements in our public transport system and economic incentives to ensure it is fair for all’. Furthermore, 63 per cent of the Assembly members supported a recommendation to ‘phase in increased road taxes for private car use and use the revenue to subsidise public transport’, explaining that this support was because ‘our aim is to progressively decrease the number of cars on the road, thereby reducing emissions generated in the production and use of cars’ (Ibid., page 89). This is consistent with other recent UK research, which found that the public mood on road pricing has moved on since the 2000s, and that in 2021 more people support than oppose road pricing as a concept, with a majority of people agreeing that road pricing would reduce congestion and pollution (Social Market Foundation. Public attitudes towards road pricing as an alternative to the current fuel duty regime, 2021).

In addition to the findings from the Climate Assembly, research into the attitudes and behaviours of a representative sample of people who live and drive in cities and towns in Scotland found that 70 per cent of respondents agreed that ‘it should be possible for everyone to undertake their most frequent journeys without a car’; while 80 per cent agreed that ‘it’s important for Scottish Government to enable people to have a good standard of living without needing a car’. The same survey identified that 71 per cent think that ‘people should be able to meet their needs within a 20 minute walk, cycle or local public transport trip from their home’ (Sustrans. Reducing car use: What do people who live and drive in towns and cities think? 2019). A summary of additional public attitudes and opinions research conducted in relation to the 20 per cent car kilometre reduction target can be found in the route map annex.

2.2 A framework for reducing car-use

In order to meet the target to reduce car kilometres by 20 per cent, people throughout Scotland must be given the opportunity and conditions to change the way they access goods, service, amenities and social connections; and businesses, public and third sector organisations will need to support their customers, clients and workforce to make those changes. It is the role of government, in collaboration with other key stakeholders, to create a policy landscape of both transport and non-transport policies that enable sustainable travel behaviours to be adopted. Individual behaviour change happens in the context of the social and material environments in which people live, and our route map sets out the interventions that will enable people to adopt better ways of living by creating a social and material context where reduced car use is a normal, easy, attractive and routine behaviour to adopt (Darnton et al. Influencing behaviours: Moving beyond the individual. The Scottish Government, 2013).

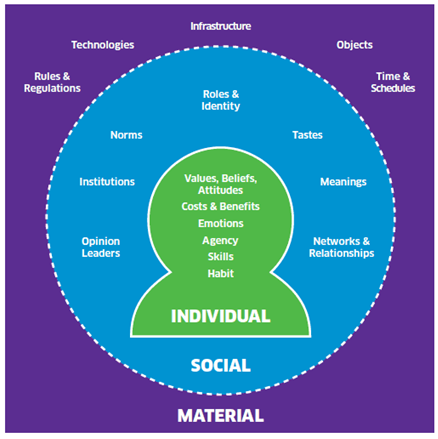

The following image shows the individual, social and material influences on behaviour. Individual influences are listed as values, beliefs and attitudes; costs and benefits; emotions; agency; skills; and habit. Social influences are listed as opinion leaders; institutions; norms; roles and identity; tastes; meanings; and networks and relationships. Material influences are listed as rules and regulations; technologies; infrastructure; objects; and time and schedules.

The Individual, Social and Material (ISM) model of behaviour change - Source: Southerton et al, 2011.

It is recognised, however, that individual-level and system-level change are interlinked, and that individual and community-level appetite for change are important drivers of system-level policy change (Wang and Khosla. Cast Briefing 06. Achieving low carbon and equitable lifestyle change. Centre for Climate Change and Social Transformations, 2021), (UNEP DTP Partnership. Emissions Gap Report 2020. UN Environment Programme, 2020). As part of our national conversation on sustainable travel behaviours, we will continue our engagement with individuals, communities, businesses and public and third sector organisations on the importance and value of reducing car use in order to enable healthier, fairer and more sustainable lives.

The following image shows the interaction between structural; social and contextual; and personal and immediate contexts for change. Structural factors are listed as policies and governance; legal and institutional frameworks; economic and incentives; supply chains and infrastructure. Social and contextual factors are listed as media and advertising; conventions; interpersonal influence; citizen participation; social norms and social movements. Personal and immediate factors are listed as knowledge and information; behaviour change; consumer choices; habits and routines and attitudes and awareness. Arrows indicate that each of the three contexts has the ability to influence and be influenced by each of the other contexts.

Interaction between structural, social and personal contexts for change - Source: UNEP DTP Partnership. Emissions Gap Report 2020.

The car-use behaviours that contribute to overall car kilometres in Scotland show that it will not be possible to reduce car kilometres by 20% by focussing on a single trip type such a commuting, or a single behaviour such as switching from car to walking or cycling for short journeys. We know that car use is higher in rural areas and that a small number of longer journeys contribute disproportionately to the overall number of car kilometres driven, yet these are the journeys that will be more difficult to switch to alternative modes.

This means we need a holistic framework of interventions to provide car-use reduction options for different trip types in different geographical areas. Our routinely collected trip data has been supplemented by survey and focus group data, described in our route map annex, to help to understand the trip types that people are willing to consider changing, the alternative travel behaviours that they are willing to adopt, the factors that would motivate them and the barriers that might prevent them from changing.

We have also made use of behaviour change theory and the published evidence base on what works in reducing car use and further details of these are provided in the route map annex. Behaviour change research tells us that people are more likely to respond to messages that ask them to ‘do’ a desirable behaviour, rather than to ‘avoid doing’ an undesirable behaviour. This has led us to develop a framework of positive sustainable travel behaviours, and to identify a range of transport and non-transport policies that will support people to adopt one or more of the behaviours. The behaviours have been selected to ensure that there are inclusive car use reduction options that can be adopted in different geographical locations by people with different personal circumstances and travel needs.

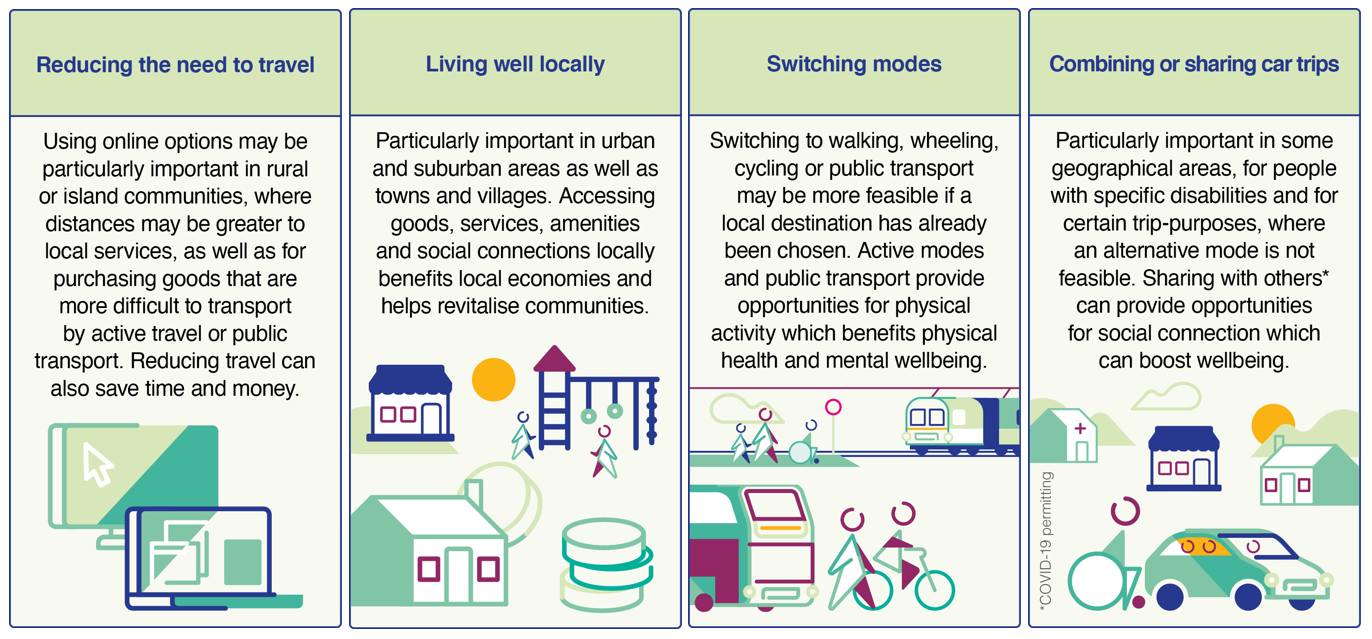

The following graphic illustrates the four desired behaviours in reducing car use:

Reduce the need to travel - The text reads: 'using online options may be particularly important in rural or island communities, where distances may be greater to local services, as well as for purchasing goods that are more difficult to transport by active travel or public transport. Reducing travel can also save time and money.'

Live well locally - The text reads: 'particularly important in urban and suburban areas as well as towns and villages. Accessing goods, services, amenities and social connections locally benefits local economies and helps revitalise communities.'

Switching modes - The text reads: 'switching to walking, wheeling, cycling or public ctransport may be more feasible if a local destination has already been chosen. Active modes and public transport provide opportunities for physical activity which benefits physical health and mental wellbeing.'

Combine or share car trips - The text reads: 'particularly important in some geographical areas, for people with specific disabilities and for certain trip-purposes, where an alternative mode is not feasible. Sharing with others - COVID-19 permitting - can provide opportunities for social connection which can boost wellbeing.'

Non-transport digital and place-based interventions are important to support people to reduce their need to travel and to enable them to choose more local destinations for work, shopping and leisure which are the three largest reasons for trips.

Transport policies will be key in supporting people to switch mode or to combine trips or share journeys where alternative modes are not available. Interventions to support people to live well locally are interlinked with those to support mode switching, as walking, wheeling and cycling become more feasible in areas where goods, services, amenities and social connections are accessible within shorter distances. In remote rural areas, policies to support a reduced need to travel, combined with the opportunity to share and combine car trips will be particularly important. We recognise that some behaviours will be more feasible in some geographical locations and for some individuals, including those with specific disabilities. The aim of the route map is to provide interventions that empower people to choose from one or more of the sustainable travel behaviours each time they plan a trip. Each of the desired behaviours also have the potential to provide other benefits to individuals, in addition to contributing to address climate change. For example:

- Making use of sustainable online options can save time and money.

- Choosing local destinations can help revitalise local communities.

- Switching to walk, wheel, cycle or public transport has health benefits.

- Combining trips or sharing a journey with others can improve wellbeing.

The sustainable travel behaviours will be supported and encouraged in line with wider government policy objectives to reduce overall greenhouse gas emissions, as well as objectives to achieve better health and wellbeing and a more inclusive economy. This is important in order to avoid route map interventions resulting in unintended consequences. We will therefore ensure that interventions to support home working are carried out alongside interventions to improve the energy efficiency of people’s homes; that interventions to support the use of online services are promoted only when the use of local alternatives are not feasible and where adequate digital infrastructure exists or will be provided, and that car-use reduction interventions are accompanied by wider interventions to decarbonise the public transport and freight sectors, particularly in the case of last-mile delivery.

Interventions to reduce car use have been considered in the context of the Capability, Opportunity and Motivation (COM-B) model of behaviour change, which recognises that for any behaviour to be enacted, people must have capability, opportunity and be more motivated to carry out the desired behaviour than any alternative behaviour. Capability refers to people’s psychological abilities (for example, knowledge and mental skills) and physical abilities (for example, dexterity and strength). Opportunity refers to the environment with which people interact, whether it be the physical environment (for example, objects and time constraints), or the social environment (for example, social cues and cultural norms). Motivation refers to mental processes that energise and direct behaviour, including reflective processes (for example, conscious decision making and inference) and automatic processes (for example, feelings and habits). Without all three enablers in place it is unlikely that the desired change will take place.

Effective transport policy, complemented with a place-based approach which provides local, accessible services, must therefore consist of interventions to help overcome barriers and support people’s capability, by providing them with knowledge of the sustainable travel options that are available; opportunity, by providing non-car options that are accessible and safe; and motivation, by ensuring non-car options compare more favourably than car, for example in terms of convenience, attractiveness and cost. We have made use of the Nuffield Ladder of Interventions and Behaviour Change Wheel approach to identify a range of intervention types and policy options to support individual-level capability, opportunity and motivation to reduce car use.

While zero-emission vehicles have an important role to play in helping us achieve our carbon reduction targets, the wider dis-benefits of using private vehicles mean that our target to reduce car kilometres by 20 per cent includes all types of private car. In line with the NTS2’s Sustainable Travel Hierarchy, switching from petrol or diesel to private zero-emission vehicles is likely to be the optimal solution only where more sustainable travel options are unavailable. Interventions to encourage vehicle-switching should therefore ensure that options to switch to digital or local access as well as more sustainable transport modes such as electric cargo cycle, public transport season ticket or car club membership are facilitated and promoted ahead of a switch to a private zero-emission vehicle.