Key trends and the need for change

In 2023 (the most recent year available), transport accounted for 33% of Scotland’s greenhouse gas emissions, and cars accounted for 39% of all transport emissions, which equates to 12.9% of total Scottish emissions (Scottish Transport Statistics, 2024).

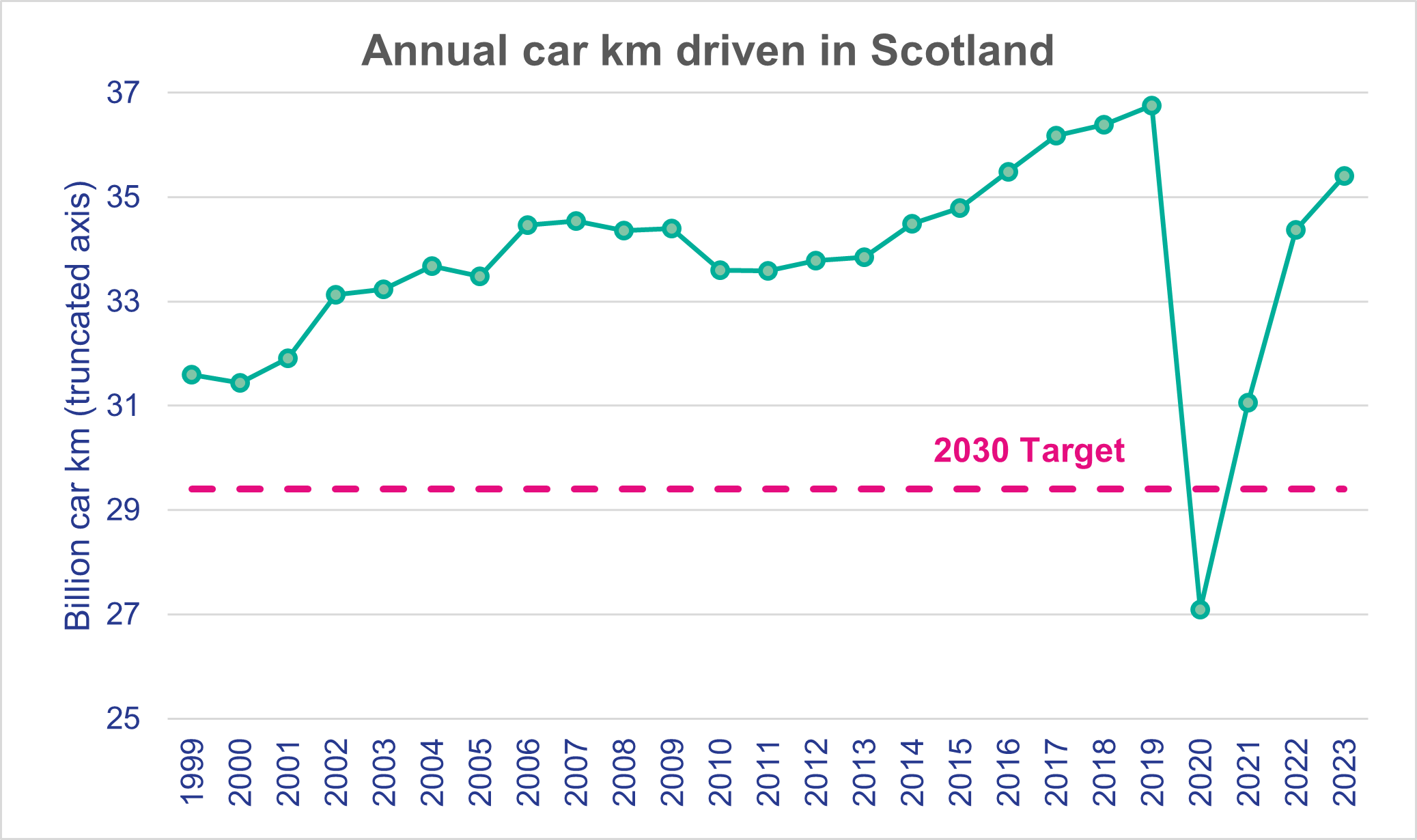

The proportion of car km driven, and overall journeys made by car, was consistently growing over time until 2019. After a steep fall in 2020 due to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, annual car km rose sharply again and are now 4% below (Road Traffic Estimates 2023: TRA0206) the 2019 baseline, meaning we are off-track to achieving a 20% reduction by 2030. This is visualised in Figure 1 below.

Policy environment

To achieve a modal shift, we need to take action in line with the principle of Triple Access Planning (Triple Access Planning for Uncertain Futures – A Handbook for Practitioners). This supports the key priorities set out in the National Transport Strategy (NTS2) and is complemented by the Sustainable Travel Hierarchy which promotes walking, wheeling, cycling, public transport, and shared transport above private car use.

This will support a wide range of national outcomes in Scotland’s National Performance Framework, the second Strategic Transport Projects Review (STPR2), and other national plans such as the fourth National Planning Framework (NPF4), Infrastructure Investment Plan, National Strategy for Economic Transformation, and the Transport Just Transition Plan.

It is evident that additional work is needed to strengthen our approach to sustainable transport demand and develop solutions that support a just transition away from car reliance for all communities. The Scottish Government continues to call for a collaborative four-nation approach with the UK Government who have key levers of power and responsibility for motoring taxation reform, including Fuel Duty, Vehicle Excise Duty, and VAT rates, to support the just transition to net zero.

The independent Climate Emergency Response Group has called for an acceleration of the shift from cars to active, public, and shared transport (Unlocking Scotland’s response to the climate emergency: 4 immediate actions to fast-track delivery for the Scottish Government), the Climate Change Committee highlight significant gaps in our transport policy pathway to our emissions targets (Progress in reducing emissions in Scotland – 2023 Report to Parliament), and Audit Scotland indicate ‘minimal progress’ on reducing car use has been made (Minimal progress on reducing car use). Behaviour change takes time and progress towards car use reduction remains challenging. It is clear now that we need to revise the level of ambition set out in the draft route map and consider the scale of the change required, alongside the transition to electric vehicles and the contribution to emissions reduction but also wider just transition and NTS outcomes.

In the 2024 Climate Change Monitoring Report the Scottish Government indicated for the first time that we are ‘off track’ in achieving a 20% reduction in car use by 2030. With 2030 approaching, current trends indicate car use is increasing rather than in decline. As a result, achieving the original target of a 20% reduction is highly unlikely. We will now therefore be revising this target, drawing on advice from the Climate Change Committee and other relevant evidence to establish a revised, longer-term target which is aligned with the timelines for the Climate Change Plan and supports our 2045 net zero target.

We will revise the existing car use reduction target, informed by the advice of the Climate Change Committee and other relevant evidence, to develop a new, longer-term target which will support our 2045 net zero target.

The need for change

The original policy intent for car use reduction was embedded in emissions reduction pathways, and this remains at the core of our renewed commitment to this policy outcome. The Climate Change Committee’s recent advice continues to demonstrate that car use reduction from mode shift can contribute to emissions reduction (Scotland’s Carbon Budgets). Whilst electrification accounts for a large majority of emissions reductions required from car use, this alone not sufficient (The Seventh Carbon Budget) to meet our net zero targets. In addition, there are wider co-benefits to pursuing a reduction in car use in Scotland. These are set out below.

Reducing inequalities

The current transport system drives inequalities by prioritising car ownership at the expense of other transport modes. A lack of reliable transport alternatives means that some people cannot easily access key services that others with a car can. This can push people into poverty as they need to own a car they cannot afford. For example, in 2023 car access increased with household income, as did the number of cars available per household: 44% of households with an annual income up to £10,000 had access to one or more cars, compared to 96% of households with an annual income of more than £50,000 and frequency of driving also increased with household income (Transport and Travel in Scotland 2023). A lower percentage of disabled people possess a driving licence (56% vs 78%), and a lower percentage have household access to a car (56% vs 80%) (Disability and Transport 2023). Lower income households, minority ethnic communities, women, older, and disabled people are less likely to own or use a car, however, the negative effects of car use – air and noise pollution, road danger, community severance, and congestion – fall disproportionately on these same groups (Health and Transport: A Guide, Transport, health and wellbeing: An evidence review for the Department of Transport). We also know bus is the mode of public transport most used by lower income groups.

Reducing car use in Scotland will therefore make it possible to re-prioritise space and investment in accessible streets and public spaces to ensure inclusive and affordable access by walking, wheeling, cycling or public transport for those who do not have access to cars.

Encouraging a wellbeing economy

The efficient and reliable movement of people and goods is essential to achieve inclusive economic prosperity. However, high volumes of traffic and inefficient road space allocation leads to congestion, which can have a significant negative impact on the economy (Submission from the Road Haulage Association (RHA) to HM Treasury, Active travel and economic performance: A ‘What Works’ review of evidence from cycling and walking schemes, 2024 INRIX Global Traffic Scorecard). Reduced traffic congestion leads to smoother traffic flow for essential services such as public transport and emergency vehicles, improving overall efficiency.

Modal shift can have economic benefits at a local and regional level. Evidence suggests that businesses significantly overestimate the number of customers travelling by car, and that investment in public realm improvements, including those to encourage walking, wheeling, and cycling, can deliver significant benefits to businesses.

Note. See references: Active Travel and Economic Performance: A ‘What Works’ review of evidence from cycling and walking schemes, Early engagement perception surveys and results, Shopping by Bike: Best friend of your city centre, Street appeal: The value of street improvements, Local business perception vs. Mobility Behaviour of Shoppers: A survey from Berlin

For example, evidence suggests people who make a journey by walking tend to spend more than people arriving by car, and that businesses experience higher footfall after the introduction of pedestrianization or active travel measures.

Note. See references: The pedestrian pound: The business case for better streets and places, Common misconceptions of active travel investment: A review of the evidence. LWCIP Strategic Report, The environmental, social, and economic benefits of sustainable travel to local high streets and town centres, (Street pedestrianization in urban districts: Economic impacts in Spanish cities, Benefits of pedestrianization and warrants to pedestrianize an area, Funding Healthy Streets Assets: Guidance for Effective Public Private partnerships in Delivering Healthy Streets Projects.

Analyses carried out in the United Kingdom and in European cities have demonstrated significant economic benefits from interventions of this kind.

Note. See references: Value for Money: An Economic Assessment of Investment in Walking and Cycling, Revitalising Altrincham Town Centre, Riding smooth: A cost-benefit assessment of surface quality on Copenhagen’s bicycle network, Bikeability and the induced demand for cycling, Why fewer (polluting) cars in cities are good news for local shops: A review of evidence on impact of low emissions zones and other ‘urban vehicle access regulations’ on retail in European cities, Efectos gastó Navidad 2018/19, Gran Vía y Madrid Central.

Any introduction of measures to disincentivise car use, such as local or regional road user charging, or workplace parking licensing, could also bring economic benefits due to their significant revenue-raising potential which must be re-invested in measures that support delivery of the area’s Local Transport Strategy (Transport (Scotland) Act 2001, Section 49, Transport (Scotland) Act 2019, Section 81).

Improving health and wellbeing

There are widespread health and wellbeing benefits to a modal shift, these include improved air quality and reduced noise; increased physical activity; reduced negative economic and social impacts of congestion; a reduction in road casualties; and opportunities for people of all ages, abilities, and backgrounds to interact in improved areas of civic space.

As well as tailpipe emissions from internal combustion engine vehicles, significant air pollution also occurs from tyre and brake wear (Tyre wear particles are toxic for us and the environment, Pollution from tyre wear 1000 times worse than exhaust emissions), which will remain regardless of any shift to electric vehicles (EVs). An estimated 1,800-2,700 premature deaths are attributed to air pollution in Scotland each year (Reducing health harms associated with air pollution). Car use also contributes to thousands of road casualties (Key reported road casualties Scotland 2023) and reduces opportunities for active travel, with physical inactivity leading to nearly 3,000 deaths in Scotland annually (Physical activity for health: framework).

Modal shift also allows for re-allocation of road space used by private vehicles to more space-efficient modes of travel such as walking, wheeling, and cycling, which creates more green and open spaces for communities to enjoy. This contributes positively to health and wellbeing (Road space reallocation in Scotland).