Context

An Economic History of Transport in Scotland

This section covers a brief overview of the economic history of transport in Scotland, and leads us into where we are today with the function and structure of our current transport network. It is useful to frame this thinking around the ‘4 Industrial Revolutions’ (figure 2.1) – a concept used by Rodrigue (2024), to consider to what degree transport played, and plays, a role. The structure of the Scottish economy is a result of successive innovations, rather than a singular event. Each Industrial Revolution builds from the previous shifts, with industry becoming more advanced throughout history as we reach today.

While it is evident that transport was fundamental during both the first and second Industrial Revolutions, and remained significant during the third, it can be argued that the fourth, referred to as Cyber Physical Systems which is ongoing now, is location neutral. There remain key impacts from and on the sector, such as autonomous and electric vehicles, as well as the potential role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in transport in the future. There remains a great deal of uncertainty around the impact of the fourth revolution on both transport and society as a whole. This uncertainty has only grown in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, which shifted travel patterns.

Figure 2.1 - The 4 Industrial Revolutions

- First - Mechanisation, water power, steam power

- Second - Mass production, assembly line, electricity

- Third - Computer and automation

- Fourth - Cyber physical systems

The First Industrial Revolution is marked by the introduction of steam and water power, transitioning from entirely human labour to human labour aided by machinery. The implementation of the new technologies took a significant time, with the period typically referred to as being between 1760 and 1840. Scotland was at the absolute forefront of this.

The establishment of the Carron Ironworks near Falkirk in 1759 predated other, perhaps more widely known, developments. The works grew quickly and by the late 1760s was producing parts for James Watt’s steam engine which greatly increased the efficiency of the existing Newcomen engine and, arguably, formed much of the basis for future developments from powering factories, the replacement of sails as the method of propulsion of ships and, of course, the development of railways. Steam turbines remain responsible for much electricity production today.

This adaptation of reliable power sources had transformative effects on textile manufacturing in the first instance, which adopted the changes quicker than other sectors. It went on to have impacts in sectors such as agriculture, mining and iron. The effects began reaching beyond these sectors and positively impacting wider society, enabling the UK to accelerate development.

The revolution that began in the UK was facilitated by improvements in transport technology, firstly through canals, and then railways. During the 18th century, the most common forms of transport were by road or sea. However, the increased production from the revolution called for a more efficient way to transport coal and iron, as these were heavy goods and the road conditions at the time could not tolerate the increased loads. In a Scottish context, the Union Canal was constructed in 1822 to connect Edinburgh with the Forth and Clyde Canal at Falkirk, enabling the transport of coal and minerals directly from Lanarkshire to the capital. The canal was later superseded by the construction of railways, notably the Edinburgh and Glasgow railway, opening in 1842. The railway network allowed for quicker transport connections between industrial centres and major cities.

The Second Industrial Revolution, commonly known as the Technological Revolution, is a period between 1871 and 1914. This saw installations of extensive railroad and telegraph networks internationally, paving the way for faster transfer of people, innovations and, crucially, electricity. Growing electrification allowed for factories to evolve the modern production line, with greater coordination between labour, machines and processes. The expansion of the railways allowed for greater, and quicker, access to markets for goods.

The Third Industrial Revolution, commonly known as the Digital Revolution, occurred after the end of the Second World War and was driven by advances in electronics, computing, and telecommunications. In terms of power sources, the advent of nuclear energy occurred during this period but this revolution was driven by the invention of the first semi-conductor transistors in the late 1940s followed by integrated circuits in the 1950s which led to the microprocessor revolution of the 1970s which in turn marked the beginning of more advanced digital developments. This sparked development of communication technologies, as well as extensive use of computer and communication technologies in the production process. Arguably these developments have reduced the role played by transport as they facilitated greater use of non face-to-face interactions. However, moving raw materials and finished goods as well as getting people to jobs remained a key component of all economic activity.

This brings us to now, the Fourth Industrial Revolution, first described by Klaus Schwab in 2015. It is characterised by the fusion of technologies blurring the boundaries between the digital, physical and biological spheres. It is argued that the breadth, depth and pace of emerging technology breakthroughs are transforming entire systems of government, production and management. These breakthroughs are in areas such as artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, biotechnology, and autonomous vehicles.

Under usual circumstances, it is reasonable to assume transitions to new ways of working that are location neutral would be a lengthy process. However, proponents of the fourth industrial revolution suggest that change will be rapid, with variations of this phrase popular, “technology has never changed so fast before, and will never change so slowly again in the future". The predicted pace of the fourth industrial revolution is expected to be one of its defining features – previous industrial revolutions took decades, and caused disruption to workers when skills became outdated at the introduction of new mechanisms. A concern for the fourth is that the pace of change will be so quick that skills will continuously become obsolete, rather than retaining value through an individual’s working life.

The COVID-19 pandemic certainly demonstrated to many organisations that the use of large central offices is not as important as previously assumed. A key determinant of future demand for transport, in terms of commuting at least, will be how workplaces change over the next few years. Changes will be driven by the attitudes of businesses and their employees, to changing working patterns.

However, it is worth considering that the pandemic also illustrated the importance of key workers for whom remote working is not possible: health workers, carers, transport workers, retail and delivery staff and others working in the service sector. Technology is already beginning to impact retail sharply, and is likely to impact on primary health care but there is greater uncertainty over how it will impact on those sectors such as personal care where the key component is the interactions between people.

These high-level ideas surrounding the fourth industrial revolution suggest a novel environment for transport. Technology is making some sectors location neutral, and will continue to evolve and change the environment further still. The impact and consequence of these changes on public transport, and private transport through electric and autonomous vehicles, is very uncertain.

Alongside the fourth industrial revolution, there will be developments that place extra demands upon the transport system. An example of this is the economic opportunities offered by energy transition and renewables. These sectors place specific demands on the transport network as they involve the movement and assembly of heavy components – often in the context of very remote locations. Both the industry specific requirements for resilient transport infrastructure and the knock on impact on where Scotland’s population is located will have significant implications for transport – a topic covered further in the section on the implications of Scotland’s geography.

In short, it’s clear that throughout Scottish history, transport has played a vital role in economic and societal development, and will likely continue to do so.

An Economic Framework for Illustrating How Transport Supports the Economy

Transport provision, i.e. the ability to move from A to B, has obvious and important economic benefits. It is uncontroversial to suggest that ensuring that transport infrastructure is functional and efficient is a pre-requisite for a functional and efficient economy. In a similar way to the rule of law or educational standards, the transport system is a foundation upon which the economy relies in order to function. Put another way, without transport infrastructure there would be no viable economy to analyse.

However, this is not useful for thinking about transport spending, beyond highlighting the risks of not delivering key infrastructure or allowing existing infrastructure to deteriorate. The focus of this part of the paper is therefore largely on the impact of a change in the level of transport infrastructure provision. A central argument put forward is that providing more or better transport infrastructure is clearly a net positive for the economy. Furthermore, there is an argument that transport investment is essential for ensuring that wider government investment can deliver economic growth.

A broader point to make – which underlines why this is so important – is that transport provision is a key economic policy lever in the context of the powers available to The Scottish Government to influence the economy. As a devolved administration, key elements of economic policy are reserved to the UK Government and there is only limited scope for The Scottish Government to exert influence in these areas. All elements of monetary policy are reserved, as are powers over critical areas of economic decision making such as immigration, trade and industry, financial services, employment law, industrial relations and consumer protection. The Scottish Government does have powers over other important areas of economic policy including education and skills, housing, tourism and economic development as well as significant powers in terms of tax and social security. But overall, the economic policy levers available to The Scottish Government are limited in comparison to national governments elsewhere. In this context, it is all the more important to recognise transport provision as a key economic policy lever. Transport makes up a significant portion of The Scottish Government’s overall budget, and a very large element of its capital spending. It is also critical to ensuring benefits are realised in other areas of devolved policy, such as housing or education and skills. And of course it directly supports economic outcomes. This chapter hopes to get across this broad point, with subsequent chapters looking at specific ways in which transport and transport policy help support the economy and improve our lives – all of which supports the argument that transport is an absolutely key part of Scottish economic policy.

Empirical and International Evidence

This is not just a theoretical argument – in an important paper looking at how transport can impact economic growth, Venables et al. (2014) note that an evidence review suggests that if all other drivers of growth were to increase by 10% and transport infrastructure were to stay constant, then growth in income would be just 9% i.e. 1 percentage point lower (and 10% lower in practice) than it would have otherwise been with proportionate investment in transport. Essentially this means that not investing in transport will hold back the growth potential of other public investment. Venables et al explore the mechanisms through which transport can impact the economy in more detail, and some of these are covered later in this paper. This idea of transport investment being a requirement for growth is also consistent with more recent DfT (2023) research around the economic impact of transport investment. This work had two clear conclusions:

Firstly, that for all modes of transport, their impacts on productivity, wages and land values are generally significant and positive – with positive impacts on employment or land values varying somewhat and depending on other factors (such as displacement and population growth).

Secondly that for ‘transformational benefits’ to occur, transport needs to be part of a wider cross-sectoral package. While transport interventions can have large benefits in isolation, these can be even greater when coupled with complementary investments – which also reflects the complex needs of places.

The 2023 DfT work was followed up with a commission to look at the existing empirical evidence more deeply. The key findings include the fact that transport investment is often associated with employment growth and increased labour and firm productivity. However the paper cautions that there is a need to look at the degree to which these economic benefits represent displacement from neighbouring areas. Empirical evidence also exists on how transport changes land use and land values. For example the International Transport Forum (ITF, 2024) find that transport interventions are associated with increases in land values of 7 to 10%. However when looking at specific geographies close to transport links, the estimated impact of transport and land values can vary substantially and may be higher for commercial land than for residential land – which is the type of land value most often assessed due to data availability. In the context of commercial land, increases in the value of land of up to 120% (offices, within 410m of transport links) and up to 167% (retail, within 70m) have been identified.

In addition to facilitating wider economic activity, transport investment itself can create economic advantages via fostering strong competitive advantages. For example, the OECD (2020) notes that “over the past few decades, Spain has invested a large amount of resources in improving the provision of transport infrastructure. A large number of projects have been implemented and the Spanish authorities have developed strong technical capacities in project execution.” This has helped the Spanish economy in numerous ways. At a basic level, Spain has been able to produce rail (as well as other transport infrastructure) more cost effectively than competitor countries – with Ineco Impulsa (2023) estimating the cost per kilometre of high speed rail in Spain to be just €17.7m in 2022. This is significantly lower than most European and Asian competitors (by comparison the cost is estimated at €167.5m per km in the UK and €42.0m per km in China). This has fiscal benefits, but also environmental ones. Within Spain and elsewhere, the availability of high speed rail has significantly reduced demand for high emissions air travel on similar routes (Jiménez and Betancor, 2012), and Spain is now able to consider restricting some internal flights due to the availability of high speed alternatives(Txapartegi and Cazcarro, 2025). By developing this degree of specialisation, Spanish companies have been able to develop a presence in railway projects in over 80 countries worldwide, including design, construction, operation and maintenance of the Mecca–Medina high-speed line and trains in Saudi Arabia (Fortea, 2015). In this sense, investments in transport can also be thought of as part of broader industrial strategy – and the chapter on decarbonisation will come back to this issue through the lens of the economic opportunities that are likely to arise through decarbonisation.

Additionally, there is also substantial empirical evidence regarding the fact that tackling inequality and climate change can help boost economic performance. Scotland's National Strategy for Economic Transformation (Scottish Government, 2022) notes that “A fair and equal society and a wealthier, greener economy are mutually reinforcing”, drawing on OECD econometric analysis (Cingano, 2014) which suggests that income inequality has a negative and statistically significant impact on subsequent growth as well as a wider economic literature (e.g. Ostry et al. (2014) and Stiglitz (2012)). Furthermore, the OBR (2024) estimates the long-run damage to the UK economy of (not addressing) climate to be equivalent to around 3% lower GDP levels by 2074 in a below 2 degrees Celsius scenario. This increases to as high as a 5% reduction in real GDP in a below 3 degrees Celsius scenario. The OBR notes significant uncertainty around these estimates, but highlights that the risks are skewed to the downside, with the adverse outcomes more likely than benign scenarios, and additional direct damages from river and surface flooding, coastal flooding and heatwaves being foreseeable.

A good starting point for understanding how important transport is in relation to inequalities is thinking about impacts on poverty. To illustrate this the Poverty and Inequality Commission (2019) made the following points, drawing heavily on a substantial academic literature (for example Crisp et al. (2018), Oviedo Hernande (2014), and Lucas et al. (2019)).

- Transport matters in relation to poverty because of its potential impact on income, household expenditure and mitigating the impact of poverty. Good, affordable transport can enable people to access jobs, education and training. This can contribute to raising household income and preventing people from experiencing poverty or enabling people to move out of poverty.

- On the other hand, poor access to transport can lock people into poverty by limiting access to these opportunities to increase income. The cost of transport can put significant pressures on household budgets. This can include the cost of public transport, or the cost of needing to run a car. Transport costs can also prevent people from travelling entirely. Transport costs need to be weighed against earnings in making decisions about taking jobs, for example.

- Access to transport can also reinforce or lessen the impact of poverty. Being unable to access or afford transport can prevent people accessing services, reduce quality of life and lead to social isolation. This can increase inequalities linked to income, such as health inequalities.

It is clear that transport provision can both unlock economic growth and help address inequalities. The next section offers a framework for understanding how transport can affect these outcomes.

Theoretical Framework

Understanding the (many) ways in which transport can affect the economy and drive growth (or other outcomes, desirable or otherwise) is the subject of a large amount of academic/policy discussion – with significant volumes of literature proposing different avenues by which transport can impact the economy. There is no single ‘right’ way to conceptualise this, and it would be easy for the entire length of the paper to discuss various ways in which transport can drive growth. For the purposes of this paper, two specific examples are used.

A seminal work on this is the SACTRA report (1998) and Transport and the Economy, which looked at the dynamic relationship between transport and the economy. It emphasised the need to see transport as part of an integrated economic development policy. Understanding transport as part of an ‘economic toolkit’ in this sense is absolutely essential, especially in a devolved context where transport is one of the areas where The Scottish Government has significant control of economic policy. Transport cannot be seen as an area divorced from the wider economy. It should be a key player within, and aligned to, wider economic policy.

The first work undertaken by Transport Scotland to visualise and understand the link between the transport system and the economy was completed in 2006, and focuses primarily on the impact of transport on the economy. It is summarised in Annex A. The approach taken here to concentrated on the impact of transport across land, labour and capital markets within the economy and the subsequent direct and productivity impacts on economic growth. This approach remains valid but does not include a wider social dimension to impacts and so is less useful now than it perhaps was nearly 20 years ago.

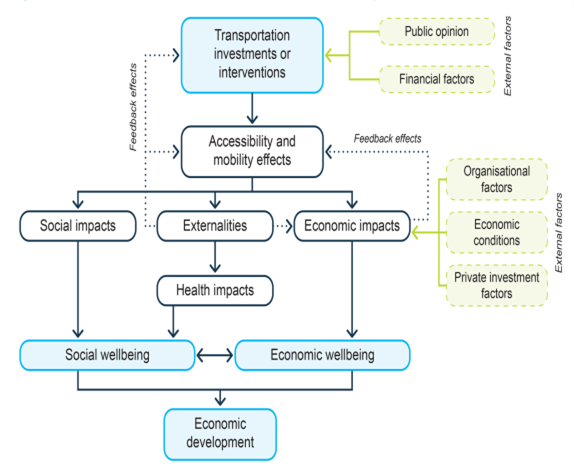

A second approach is shown below, in Figure 2.2. This is taken from a report by the New Zealand Ministry of Transport (2016) into the Contribution of transport to economic development. This represents a good lens to use for looking at the relationship between transport and the wider Scottish Economy. It is both relatively simple and highly relevant for the Scottish context, with both governments having a similarly broad understanding of how transport affects the economy. This includes realising the potential social and health benefits that a transport intervention can deliver – as well as understanding how inequalities can impact and be impacted by transport. Transport feeds into wellbeing in addition to just supporting classic ‘economic impacts’ such as an increase in output etc. This is, of course, far from the only model that could be discussed. Amongst alternatives for example, Greener Vision (accessed 2025) publish one that is far more focussed on how the policy cycle supports GVA growth and the OECD (2007) have one that focusses more on impacts via the specific lens of market access and the transportation of goods. However, for the reasons set out above, the New Zealand Ministry of Transport framework is both helpful and relevant for the purposes of this paper.

The same paper eloquently describes some of this complexity:

“Transport investments have multiple over-lapping economic impacts, which can be assessed from several perspectives. The initial impacts of investments ‘ripple’ through the economy both spatially and over time, manifesting themselves through changes in residential and industrial location, property prices, changes in the supply and demand for labour, and differential effects on the economy in any given area/region relative to other areas/regions.”

A key point is therefore that context is particularly important when considering the value that an individual transport project may provide and that the impacts of an individual investment may be complex and vary over time. Rather than trying to summarise all of these arguments, this paper will aim to provide a series of more tangible explanations and case studies illustrating how the transport sector helps deliver growth and tackle inequalities.

A Guide to How Much Economic Activity Transport Supports

In more practical terms, the aim of this section is to help illustrate the amount of economic activity that Scotland’s transport network currently facilitates.

Travel makes up a significant part of our lives. 64% of people had travelled the previous day when asked as part of the 2023 Scottish Household Survey (respondents are 17+). The average number of trips per adult the day before their survey interview was 1.59. This is somewhat below pre-pandemic levels of travel (74% and 1.94 respectively).As in previous years, the car was the most popular mode of transport for journeys made in 2023, with 51% of journeys made as a car driver. Over 60% reported driving at least once per week and almost 35% drive each day. 66% of adults made a journey of more than a quarter of a mile by foot to go somewhere in the last seven days, 25% of adults used the bus at least once per week in 2023, and 9% used the train. In terms of volume, Scottish Transport Statistics shows that car traffic in Scotland reached 35.3 billion kilometres over the year, equating to an average of around 96.9 million vehicle kilometres per day. ScotRail usage was recorded at 81.2 million passengers annually, translating to an estimated 222,000 daily rail passengers. Ferry services carried 9.7 million passengers, averaging around 26,500 passengers per day. Furthermore, bus travel was the most widely used form of public transport, with 334 million passenger journeys made, roughly 916,000 daily bus passengers. This paper is written with recognition of the strong, diverse and well-utilised transport network that Scotland has, and the importance it holds to each of us.

Employment

Looking specifically at travel to work, there was a slight increase from 2022 to 2023 in the proportion of working people reporting travelling to work at least one day per week (from 80% to 83% compared to 80%). This remains lower than in 2019, when the figure was 95%. However, it is clear that a large majority of employment requires some degree of transportation.

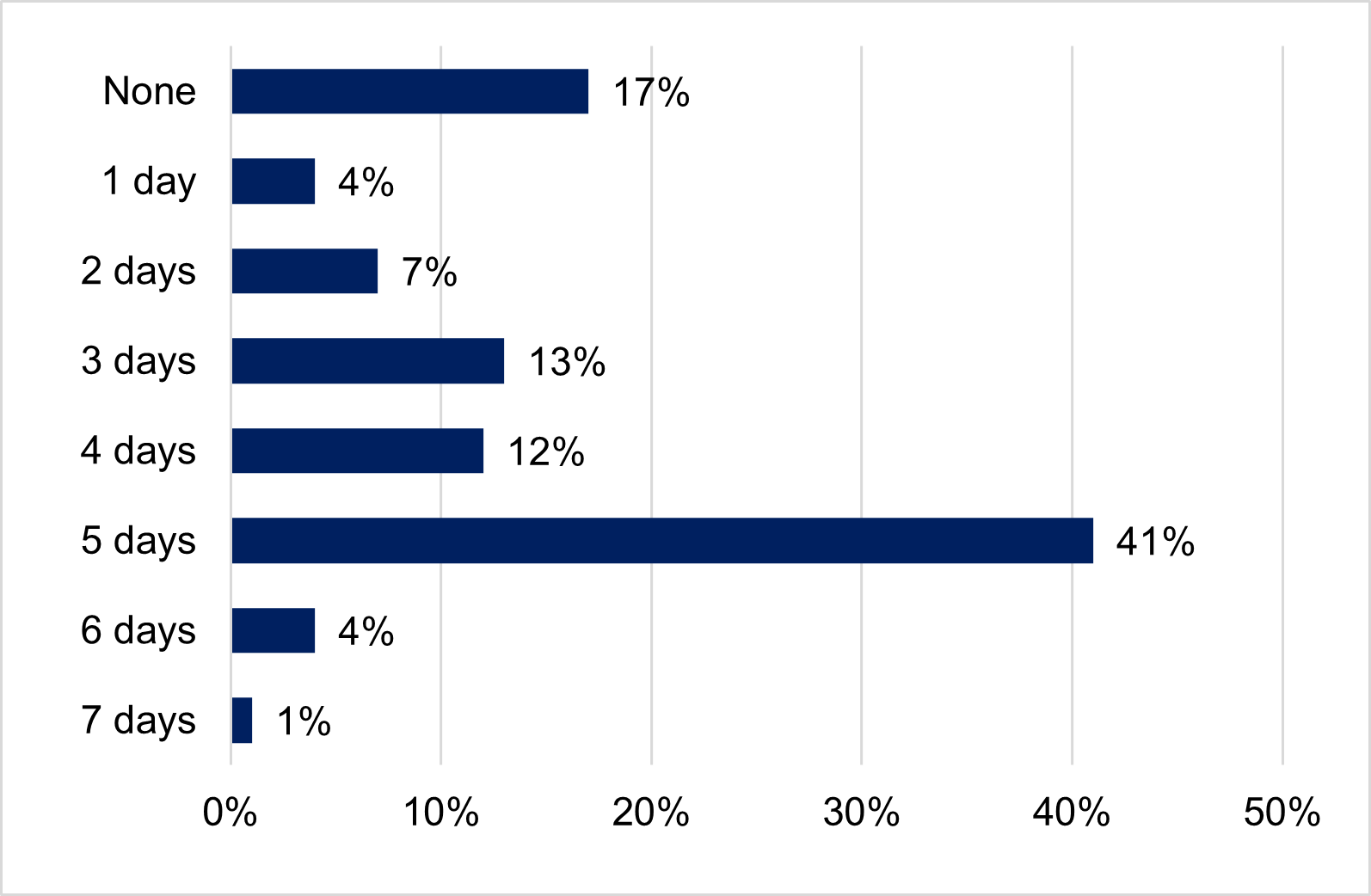

Figure 2.3 (below) looks at the number of days workers travelled to work per week – with a large majority (71%) travelling to work at least 3 days a week. Prior to the pandemic the numbers were higher still: as high as 90% in 2019. Only 17% of people reported travelling to work no days each week, and even in this case, transport is often necessary to facilitate efficient home working. As such, a large majority of employment in Scotland depends on transport, with the median worker travelling to work 4 times per week and the most common working pattern seeing individuals commute to work 5 times a week.

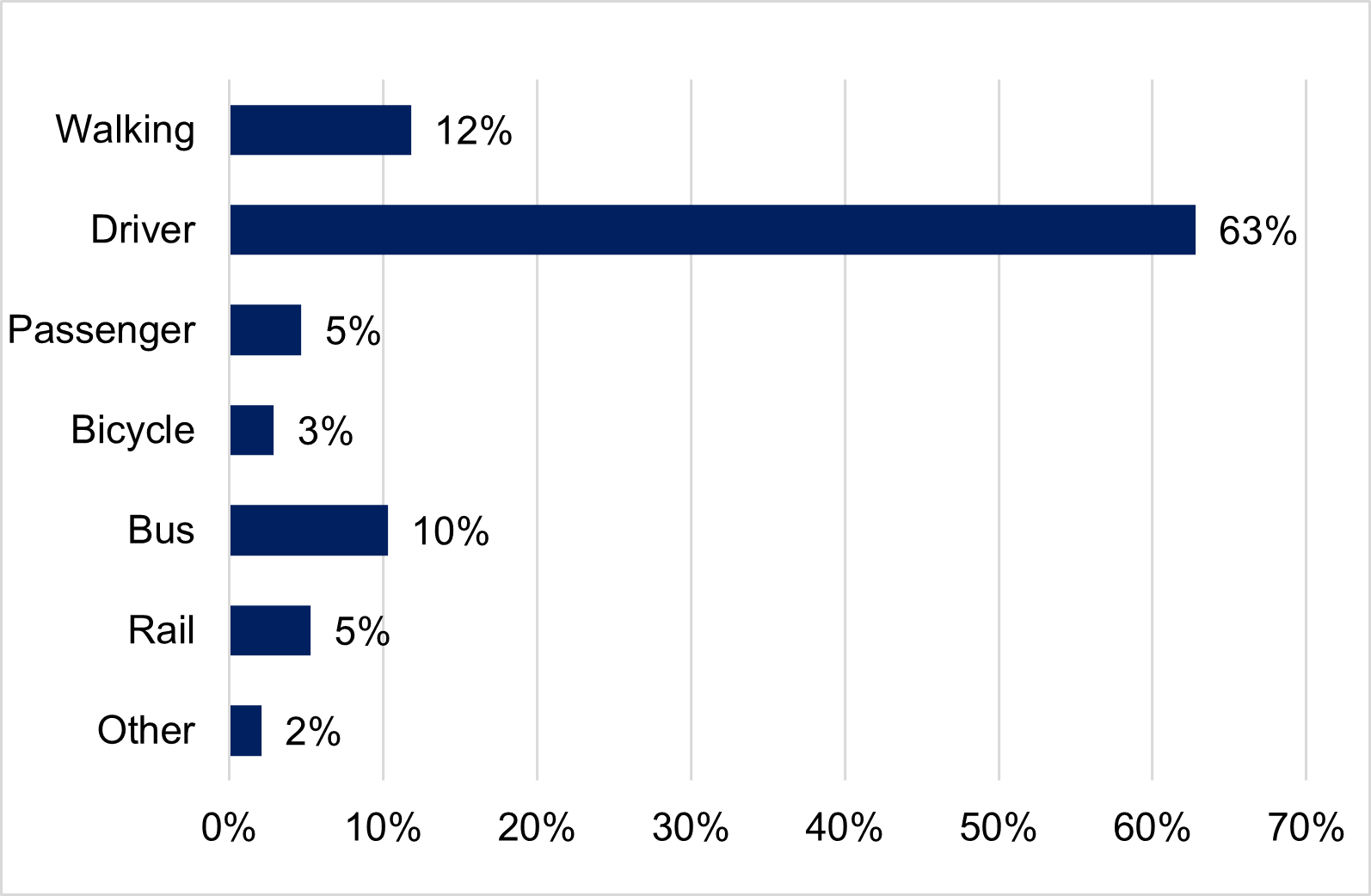

In 2023, two thirds of people who travelled to work (68%) usually travelled by car or van, making this by far the most popular mode of travel used to get to work. A full breakdown is given in figure 2.4, below.

Trade

The transport network is absolutely essential to facilitating economic activity and trade, via the transport of goods – as Scottish Transport Statistics can show us. A huge amount of commercial freight travels to, within and from Scotland every year. Looking at Heavy Goods Vehicles in particular, approximately 134 million tonnes of freight was lifted by UK HGVs on journeys originating in Scotland in 2023. A large majority of this freight had a destination within Scotland (around 118 million tonnes) with the other 16 million tonnes of freight going to the rest of the UK. The role of Scotland’s road network in supporting the economy is discussed further in the Geography chapter later in this paper (page 61).

Looking specifically at international trade, some of this road freight travelled out with the UK (approximately 200,000 tonnes). However Scotland’s primary transport mode for exporting goods remains shipping. Exports from Scotland’s 11 major ports totalled almost 23 million tonnes in 2023 (with a further 47,015 tonnes of freight carried by air).

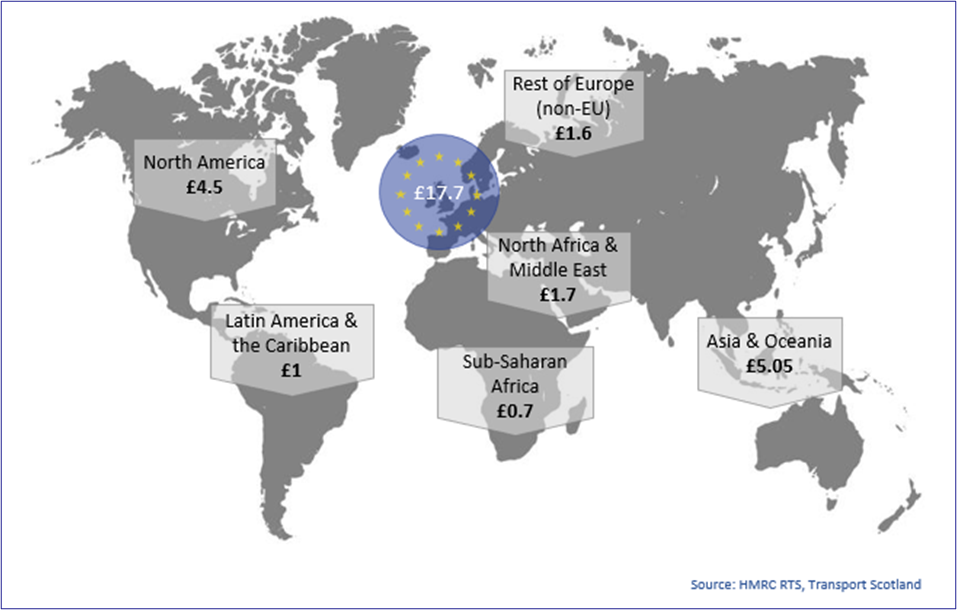

Transport is at the heart of ensuring that goods arrive where they need to be to facilitate economic activity, and almost all trade in goods (including exports) rely on the transport network. In monetary terms rather than in terms of weight, Figure 2.5 shows the value of Scottish international goods exports, by destination according to HMRC (2025) statistics. There were £32.3 billion (in current prices) worth of Scottish goods exported internationally in 2024, a slight decrease compared to 2023. Within this, the EU remains Scotland’s largest export market, totalling £17.7 billion. EU exports make up a 55% share of total international exports, broadly in line with previous years.

Tourism and Business

Transport is of course crucial in both facilitating visitors to Scotland, supporting the growth of Scottish businesses, and fostering international connections.

By definition, transport is a key aspect and facilitator of tourism. According to the Great Britain Tourism Survey (2025), there were over 75 million tourism day visits taken by Great Britain residents in 2024 with an associated spend of £4.0 billion. This facilitates economic activity, but also preserves a key social function too – with visiting friends or relatives as the most common reason for tourism day visits. And while the main destination for Scotland’s tourists is to towns and cities, it also has an important impact across Scotland’s whole geography. In the years preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, visitor spend in the Highlands and Islands region was worth around of £1.5bn and HIE (accessed 2025) notes that, in some areas, jobs in tourism represented up to 43% of the workforce.

Scotland is also a key global destination for tourism. According to the ONS’ International Passenger Survey (IPS) (2024), sponsored by Visit Scotland, international travel to Scotland continued to strengthen following the COVID-19 pandemic in 2023. Visit numbers, nights spent and visitor spending were higher in 2023 than they were in both the previous year and pre-pandemic (2019). Scotland hosted a total of 4 million visitors, who stayed for 34.4 million nights and spent £3.6 billion, directly infused into the Scottish economy.

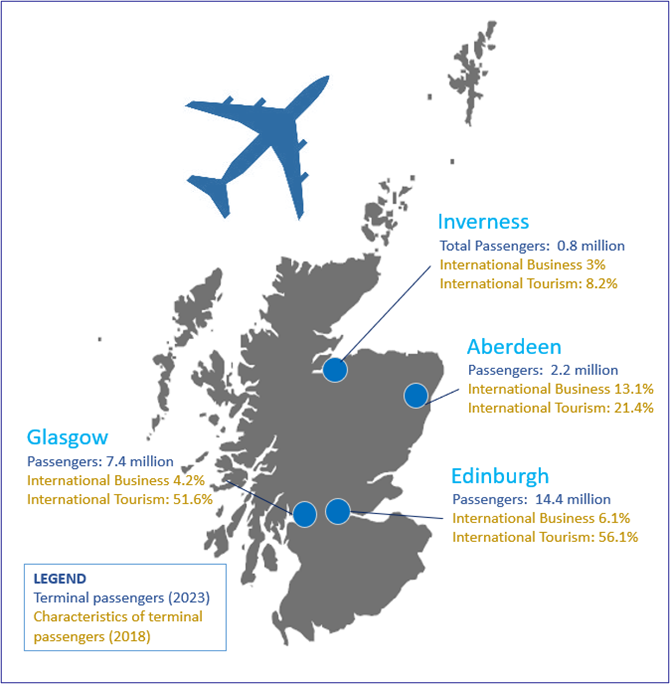

Looking at terminal passenger figures in Scottish airports, there was 26 million passengers in 2023, up from 21.5 million in 2022 and 7 million in 2021, pointing to continued recovery from the pandemic (Scottish Transport Statistics, 2025). Edinburgh was the busiest airport, with 14.4 million passengers. This is followed by Glasgow (7.4 million), Aberdeen (2.2 million) and Inverness (0.8 million). From Scotland’s airports, there are connections to 55 countries (international, excluding rUK), and over 220 destinations directly. The International Passenger Survey highlights the range of international visitors Scotland receives. The most popular region of residence, in 2023, was Europe (2.3 million tourists), followed by North America (969,000). North American visitors accounted for 24% of all inbound visits and 39% of total spend by tourists.

There is also data available on characteristics of terminal passengers from 2018, which, although dated, shows that patterns are broadly in line with 2013 and therefore suggests trends are relatively stable. As shown by Figure 2.6, Edinburgh had the highest proportion of international passengers (62.2% of total passengers), with 13.1% of all passengers travelling for international business, and 56.1% travelling for international leisure. Aberdeen has the largest proportion of international business passengers at 13.1%, double the proportion of Edinburgh. Scotland’s economy is driven by a large service sector (accounting for around three quarters of all economic activity – according to recent Scottish Government GDP estimates), so ensuring global connectivity for Scotland’s businesses is hugely important.

Figure 2.6 (below) describes both of these data insights – although it should be noted that the total volume of passengers and the proportions involved in international business and leisure do not align due to the difference in time period for which data is available.

Scotland’s international links are not limited to just tourism and business, but also play a key role in supporting other sectors. An obvious example is Scotland’s universities, which represent one of our greatest assets and an area of competitive advantage. International students play a huge role in supporting these universities and in boosting the wider Scottish economy. Scotland’s transport network is critical in facilitating international students to live and learn, bringing new cultures and experiences to our universities. Scotland’s international education strategy notes that in 2022/23 more than 83,000 students from over 180 different countries came to study at Scottish universities, and international students made up a quarter of the total student population. The net contribution in 2021-22 of international students in Scotland to the UK economy was estimated to be £4.21 billion (Scottish Government, 2024).