Decarbonisation: The Key Role Transport Needs to Play in Meeting Scotland’s Climate Ambitions and the opportunities it offers

Transport’s Role in Scottish Emissions

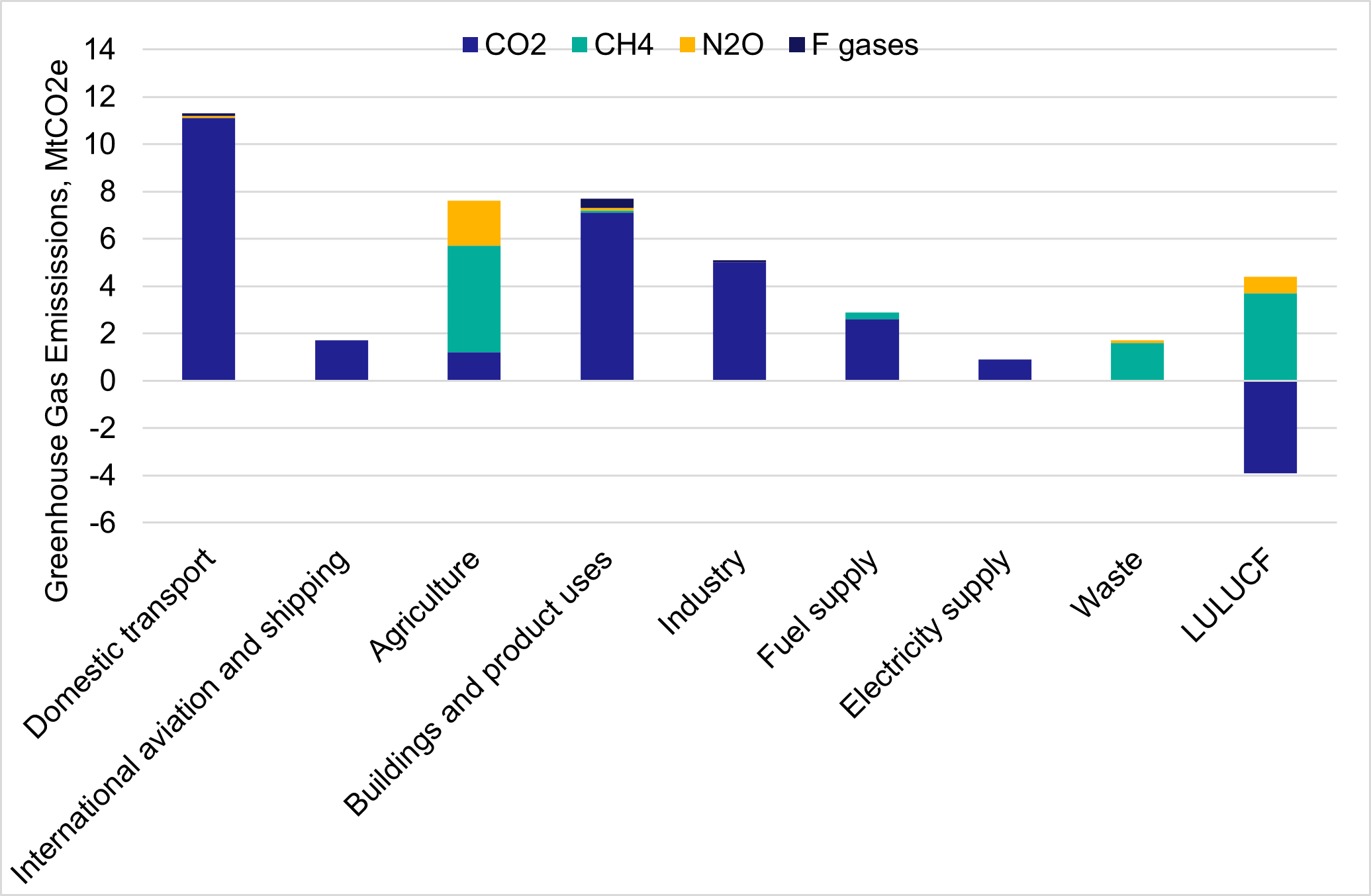

Transport is Scotland’s largest source of emissions, as can be seen in the chart below which looks at emissions (in CO2 equivalent terms) from all of Scotland’s major sectors, and across different emission types.

In 2023, Transport including international aviation and shipping (IAS) accounted for around 33% of total Scottish emissions, making transport the largest emitting sector for the ninth consecutive year. This is a rise on recent years, in terms of share of overall emissions, but in line with pre pandemic averages.

The Financial Benefit of Decarbonising Sooner

A first principle to acknowledge in discussing the likely costs of decarbonisation is that while these financial costs are large, the costs of not decarbonising are significantly larger. The Stern review, a landmark study published in 2006, estimated that the overall costs of unmitigated climate change to be equivalent to 5-20% of global GDP each year (Stern, 2006). The Climate Change Committee, which has a purpose to advise the UK and devolved governments on emission targets, estimate that the significant investment required in infrastructure and technology will be more than offset by operational expenditure savings (CCC, 2020). They estimate a net benefit to UK consumers of £8 billion per year in 2035 (compared to a counterfactual of no abatement actions).

However, to get to the stage of reaping net benefits, significant initial and ongoing investment is required. For example, investment in vehicles and charging infrastructure from both the public and private sector. In some areas of transport, estimating a financial cost of these interventions at sufficient scale is difficult as the technology is still emerging. The IPPC (2022) note that “There are few obvious solutions to decarbonising heavy vehicles like international ships and planes. The main focus has been increased efficiency, which so far has not prevented these large vehicles from becoming the fastest-growing source of GHG globally.” The CCC estimate the combined public and private annual capital cost of decarbonising transport in the UK will reach £12 billion per year in 2035.

Achieving the levels of funding required to address the climate crisis is not just a Scottish or UK specific challenge – nor is it specific to transport alone. There is still a need for both governments as well as businesses and individuals to invest significantly more in measures aimed at climate mitigation in order to achieve Net Zero at a global level. The Climate Policy Initiative (2023) estimate the requirement for climate finance to be US$6.2 Trillion by 2030 – with transport playing a significant part.

There is wide acknowledgement of a large gap in terms of financing for transport decarbonisation, but a general consensus that the additional funding required amounts to hundreds of US$ billions by 2030. For example, a range of US$244 to US$944 billion through 2030 is provided by Lefevre et al. (2016). More recent estimates also fall within this range - Transport and Environment (2024) estimate that “Europe needs €310 billion each year by 2030 to deploy clean Technologies” while the SLOCAT (2022) have estimated that “There remains an estimated annual financing gap of around US$ 440 billion for transport infrastructure to meet the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.” A critical point here is that significant private as well as public investment is needed, with the Transport and Environment report noting that “The bulk of the investment – 87% by 2030 – will come from private investors, including manufacturers, banks, and institutional investors”. As such, harnessing wider investment is absolutely key to financing decarbonisation in a transport context.

There has been positive progress in this regard, with at a global level a review by the UN Environment Programme (2016) noting that financial institutions were recognising the importance of supporting sustainable development and that financial regulators were acting to increase transparency and assist in the effective reallocation of capital towards sustainable investments.

Transport Scotland recognise that investment in active and public transport is vital for our climate ambitions by providing viable and sustainable alternatives to car use. In The Scottish Government’s Budget 2025-26, nearly £2.9 billion (which includes resource, capital and non-cash funding) will support our bus, rail and ferry networks, low carbon programmes and active and sustainable travel. £54.4 million will be targeted at programmes to reduce the impact of transport on our environment to support low carbon, zero emissions and climate change and a further £188.7 million on Sustainable and Active Travel will increase our investment in walking, wheeling and cycling, and improve connections into the public transport network. Despite these considerable investments, the challenges of achieving the funding levels necessary (both in government and in the private sector) should not be underestimated.

The delivery of public electric vehicle (EV) charging underpins the adoption of EVs in Scotland and the phasing out of Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) vehicles – a key part of meeting Scotland’s net zero targets, with cars and vans accounting for 17% of CO2 emissions in 2022. In 2011 the Scottish Government took the bold step of investing in public EV charging infrastructure ahead of demand to build confidence in the early adoption of EVs. In the early years of EV adoption, the vast majority of public charging infrastructure was funded by the Scottish Government and was largely free to use to incentivise early EV uptake. By the end of 2021, Scotland had close to 4,000 public charge points. However, research undertaken by the Scottish Futures Trust (2021) for the Scottish Government in the same year, suggested that if Scotland was to have a public charging network that met its future needs, then the scale and pace of investment in public EV charging infrastructure would need to be accelerated to meet growing demand and new delivery models, and enabling increasing private sector investment would be required.

Private sector investment has played a role in growing Scotland’s public charging network since the first modern EVs appeared on Scotland’s roads in the 2010s, however it was only when tariffs began to be introduced across the ChargePlace Scotland network in 2022 onwards that the scale of private sector investment became increasingly significant. The Scottish Futures Trust estimates that the private sector invested approximately £25 million to £35 million in expanding public EV charging infrastructure in Scotland in 2023 and between £40 million and £55 million in Scotland in 2024 (see a Vision for world class public electric vehicle charging - Transport Scotland (2023), and the Draft Electric Vehicle Public Charging Network Implementation Plan - Transport Scotland (2024)). Today Scotland has over 6,800 public charge points and over two thirds of charge points have been funded and delivered by the private sector. However, private investment is geographically uneven and is largely being targeted towards areas of the strategic road network with higher traffic volumes and Scotland’s towns and cities. To ensure a return on their investment, charge point operators and their investors target these high-utilisation locations and even then, it can take between seven to ten years for a public charging site to start to make a return on the initial cost of investment (KPMG for Transport Scotland, 2024). This risks leaving rural and island communities underserved for lack of private sector investment. For this reason, Scottish Government funding such as the £30 million EV Infrastructure Fund and the £5 million Rural and Island Charge Point Fund support the development of public EV charging in those areas of Scotland less likely to benefit from stand-alone private sector investment.

Another example of public/private sector collaboration is the Scottish Zero Emission Bus Challenge Fund (ScotZEB) which aims to support swift and substantial changes in the bus market. This fund is focussed on supporting innovative business models orientated around zero-emission buses and infrastructure – encouraging bidders to make arrangements with partners or collaborators. Phase 1 awarded £62 million and resulted in 276 zero-emission buses and associated charging infrastructure. Phase 2 sees public sector capital funding allocated to forward-thinking companies and supports a change in narrative to zero-emission vehicles becoming the default for operators. It also expanded eligibility to coaches and community transport providers. ScotZEB 2’s collaborative approach to decarbonising the bus sector has seen success, with companies working together to maximise the benefits of infrastructure supported by government grants. A pan-Scotland charging network comprised of electrified bus and coach depots is being supported through the scheme, which will be open where possible to other members of the ScotZEB 2 consortium, and also to other road users. These open depots provide additional revenue streams to the operators who own them, as well as provide potential charging opportunities to other heavy duty road vehicles, which will help to provide confidence to that sector that transition at scale is possible.

Transport Scotland are working in partnership with Heriot-Watt University and haulage fleets to understand where energy infrastructure will be required for trucks on longer journeys. Haulage fleets have shared data enabling a better understanding of routes travelled and Heriot-Watt University’s modelling identifies where en-route charging and fuelling will be needed to unlock the transition in Scotland. This work explores both charging infrastructure and hydrogen refuelling and an initial iteration covering around 1% of Scottish trucks was published in September 2024. This work is also supporting investment planning by both electricity networks and commercial financiers as they develop business cases for supporting Scotland’s heavy duty vehicle charging network, as well as of interest to road haulage fleets.

Adaptation to climate change represents another area where huge costs could be avoided by investing in ensuring the resilience of our transport network to the likely impacts of climate change. Impacts are already being felt across Scotland’s transport network, perhaps most notably at the A83 Rest and Be Thankful. This is one of Scotland’s most well-travelled (and famous) roads, but the route has become more prone to closures in recent years due to landslips, made more likely by the changing climate. This had led to an almost 100km diversion for many people. The proposed long-term solution - consisting of a 1.4km long debris flow shelter on the line of the existing A83, was announced in June 2023. It is estimated to cost a significant amount (between £405 million and £470 million, at 2023 prices), but the value of maintaining the resilience of a key part of Scotland’s strategic road assets is also extremely large (see discussion of the Trunk Road Network within the Geography chapter for a further discussion).

The Economic Opportunity Offered by Addressing Climate Change

As discussed above, climate change investment is expected to bring net benefits to consumers and provides great economic opportunities. However, it is important to not only conceive of these benefits costs avoided – but also to look at the economic opportunities that decarbonising the sector offers. For example, looking at opportunities within the labour market, increasing demand for low-carbon, Net Zero goods and services has implications for workforce structure. The CCC (2023) paper ‘A Net Zero workforce’ estimates there are already 250,000 jobs generated in the transition process, with more opportunity for high-quality employment across Scotland and the UK. Looking at the extent to which jobs are at risk, it estimates that that there are significantly more UK workers who are employed in sectors that could be expected to grow as a result of Net Zero (10%) rather than in sectors where phase down is expected (0.3%).

The transition to Net Zero will have widespread implications for transport across the operation of the existing network, construction of new railways and roads, as well as vehicle and battery manufacturing, and sustainable fuel sources. At a UK level, the Climate Change Committee identify the following as sectors within transport likely to see employment growth:

- Rail Operation and Construction of Roads and Railways (expected growth)

- Electric Vehicle and Battery Manufacturing, and Sustainable Aviation Fuels (with the CCC noting these sectors are contingent on UK growth as well as industry and policy action).

Within a Scottish context, Scotland’s draft Transport Just Transition Plan (Scottish Government, 2025) identifies three key opportunities for growth as part of decarbonisation, which differ somewhat from the CCC analysis at a UK level. The first relates to decarbonisation of heavy goods vehicles, noting that Scotland currently has a base of companies in the Heavy Duty and Niche vehicle manufacturing sectors. The second is Sustainable Aviation Fuel, due to Scotland’s skills base, natural resources and existing infrastructure. The third area is charging and refuelling infrastructure with the report noting that “as many as 15,000 new roles could be required to support the uptake of ULEVs by 2050, for services including maintenance and repair, production, and infrastructure installation”.

Outside of immediate employment in these core sectors, the effects of the transition to Net Zero within transport will also impact upon the wider economy. This is particularly true for electric vehicles (EVs). EVs are significantly more efficient than conventional fossil-fuelled vehicles. The CCC estimate initial investment will be offset by lower operational expenditure from around 2030 and operating costs savings will increase to £20 billion annually (ibid). Furthermore, electric vehicles will have transformative impacts on how our road network operates – they bring opportunities to redesign, operate and maintain our road network – with the potential to explore and move away from a network formed around fossil fuel distribution. Indeed there is scope for electric vehicles to become an important contributor to Scotland’s economy while not in use – via the storage and generation of energy, with owners becoming ‘prosumers’ – producing and consuming via their EVs (Kühnbach et al., 2024).

Realising these economic opportunities will require both planning and investment. Ensuring that jobs are delivered will involve substantial retraining and skill development, while government will have to think carefully about the geographic risks and opportunities presented. For example, the CCC identify Grangemouth as a possible hub for hydrogen and Carbon Capture and Storage technology which will be clustered around particular geographies due to the nature of the infrastructure required. There may also be opportunities offered for job creation in island and rural locations in terms of construction e.g. wind farms. Beinarovica et al. (2024) forecast that the Highlands will account for a disproportionately large number of these Jobs by 2030. It is important that opportunities within transport are considered in this regard, but also that transport can support the development of growth industries in other areas – for example ensuring our road network is well equipped for the challenges of transporting large renewables or decommissioning equipment.

Ensuring a Just Transition

In addition to noting the challenges and opportunities that decarbonisation can pose to the economy, it is also important to consider how it will affect all of society, especially the most vulnerable. Any period of significant transition will have a substantial distributional effect – creating winners and losers. It is recognised internationally that “the effects of climate change disproportionately affect those in poverty, and can exacerbate economic, gender and other social inequalities, including those resulting from discriminatory practices based upon race and ethnicity; the transition towards net zero will affect, most acutely, those in workforces in sectors, cities and regions relying on carbon-intensive industries and production”. This is the text of a declaration by The EU and 10 Member States supporting the conditions for a just transition internationally (adopted at the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference in 2021). It helps articulate why it is vital to identify those who may be negatively affected (e.g. individuals or communities that see job losses) and ensure there is a plan to address the ‘losses’ suffered.

One key element that needs to be considered is that of jobs – those lost, created and affected by climate change. The Climate Change Committee Net Zero Workforce Paper cited earlier has a substantial discussion of this aspect of the decarbonisation process. Looking back toward large economic transitions in the past such as the shift towards a service economy and the move away from coal, they conclude that “even a relatively small number of job losses could result in significant and long-lasting negative impacts for local communities if they are economically dependent on that sector. For this reason, it is important to consider both absolute jobs in a given sector as well as the contribution to regional employment of a given sector” (Ibid). The draft Transport Just Transition Plan discussed above also captures this point in looking at transport areas where jobs may be lost. It notes “The employment facing the most serious impacts are likely to be vehicle repair and maintenance jobs – particularly at small local garages – and petrol station jobs” (Ibid). Transport also has a significant role in cushioning impacts from other parts of the economy moving to Net Zero – and so integration with wider just transition and economic strategies is crucial.

The SLOCAT (Sustainable, Low Carbon Transport) Partnership (2023) emphasise the need to include workers within the sector in a “social dialogue, incorporating the voice and knowledge of workers into policy and planning” and also note the need for specific action on the gender and age (specifically young workers) dimension of transport jobs.

More broadly, there is also the issue of how the transport system is designed and how it meets the needs of its users. The International Transport Forum and FIA Foundation have highlighted that policies for decarbonising transport will impact women, other excluded groups, and men differently. They note the importance of addressing gender inequalities within the transport sector as well as gender analysis of transport interventions. While typically seen as distinct areas, there is evidence that integrating gender analysis and increasing women’s participation in the sector will increase the effectiveness of attempts to reduce emissions (Bassan and Ng, 2022). Similarly, authors writing for Changing Transport have highlighted specific aspects where progress could be made. Bernhard (2024) has highlighted the gender dimension, with focuses on the need for future transport planners to consider gender inclusive cities. Stutz and Vasquez (2024) have explored the benefits of feminist transport systems in terms of empowering communities and lowering emissions. This is an issue acknowledged in the draft Transport Just Transition plan, which notes that women make up just 18% of the transport workforce. With evidence of shortages in the workforce and an aging demographic of transport workers (40% are over the age of 50), there is a significant opportunity to address this gender imbalance.

In a Scottish Context, the Just Transition Commission (2021) has been established and has recommended that The Scottish Government should identify existing inequalities in addition to mitigating injustices that may arise because of climate change as part of efforts to achieve Net Zero. This will play a pivotal role in terms of shaping Scotland’s approach and policies towards both climate change and the economy going forward. As part of efforts to ensure a just transition, Transport Scotland (2023) have acknowledged that our future transport system should become more equitable, making sure everyone’s needs are met and helping to reduce existing inequalities. The draft Transport Just Transition Plan referenced throughout this section sets out in more detail some of the issues as well as positive action that The Scottish Government is committed to taking in this area (Scottish Government, 2025).