Helps deliver inclusive economic growth

This chapter considers the following indicators:

- Indicator 3A: Journey Times to Basic Services

- Indicator 3B: Journey times to areas of employment and education for individuals

- Indicator 3C: Performance Measures of Public Transport Modes

- Indicator 3D: Barriers to Public Transport Use and Access

- Indicator 3E: Tourism/Visitor Numbers

Indicator 3A: Journey Times to Basic Services for individuals

To demonstrate journey times – via walking and public transport – to basic services, Transport Scotland commissioned analysis to determine the fastest available journey time from the population weighted centroid (PWC) of each data zone to the closest example of a key service within specific time periods on a weekday. Data zones, of which there are 6,976 in Scotland, are the small area geography used by the Scottish Government to allow statistics to be available across a number of policy areas, and represent areas with populations of between 500 and 1,000 household residents. The data zones used in this report are based on the small area statistics from the 2011 census. This dataset was developed using the TRACC software, which uses public transport timetables to make journey time estimations.

Public transport is defined here as trains, buses, coaches, trams (Edinburgh Tram and Glasgow Subway) and ferries, using pre-pandemic data on service timetables (from January 2020). The time periods in question were as follows, on a Tuesday:

- GP – between 6:30am and 10:30am

- Hospital – between 6:30am and 10:30am

- Primary school – between 6:00am and 9:00am

- Secondary school – between 6:00am and 9:00am

- Further education – between 6:00am and 9:00am

- Higher education – between 6:00am and 9:00am

- Large food outlets – between 10:00am and 2:00pm

- Train stations – between 9:00am and 1:00pm

- Airports – between 6:00am and 10:00am

The analysis either returned a single result for the length of the time this journey would take or received a null result in the event that the journey was not possible or the PWC could not reach public transport within 800 metres and did not permit walking to the destination. These estimates represent the first iteration of this sort of analysis, and it should be emphasised that there are a number of important caveats to this work, discussed in Annex B of this report. In short, they include:

- Only one result is needed to return a result within the time frame, so the volume of available journeys is not reflected in the results

- The analysis returns the fastest available journey time available, so may not represent all journeys

- The nearest destination is not necessarily the preferred or required version of the service in question, and

- The services included here do not exhaust the number of services that could conceivably be analysed using this method

Approaches to address these limitations will be considered and developed as the analysis proceeds over subsequent monitoring and evaluation reports.

Results

For the purposes of analysis and presentation, the findings were grouped into the following accessibility tiers:

- Within twenty minutes

- Twenty to forty minutes

- Forty minutes to an hour

- One to two hours

- Two to three hours

- Three to four hours

- Public Transport Access but Limited Access

- No Public Transport Access and not Walkable

For clarity, the tier of ‘Within twenty minutes’ includes journey times up to and including 20 minutes, but no journey times that are longer than this. For example, a journey calculated as exactly 20 minutes would be included in ‘within twenty minutes’, but a journey time equal to 20 minutes and 2 seconds would be contained in “twenty and forty minutes”. Similarly, “twenty to forty minutes” includes any journey time over twenty minutes but up to and equal to forty minutes, and so on.

The ‘Public Transport Access but Limited Access’ tier refers to areas with access to public transport but that did not have a route to a key service within the allotted time period. The ‘No Public Transport Access and not Walkable’ tier refers to data zones where there was not access to public transport within 800 metres of the population weighted centre of the data zone and the service could not be accessed via walking. While this does not mean that no residents within these data zones could or do access public transport, it highlights areas where accessibility is more limited.

In the entire dataset, there were 30 data zones that had access to public transport could not access any of the above essential services within two hours (0.4% of the dataset) and nine that could not do so during the allocated periods (0.1%). By comparison, 5.2% of data zones did not have access to public transport in the terms described above. Of these, 4.7% could not access any of the services listed above, compared to 0.6% that could access at least one (via walking). A list of these data zones is provided in the accompanying dataset.

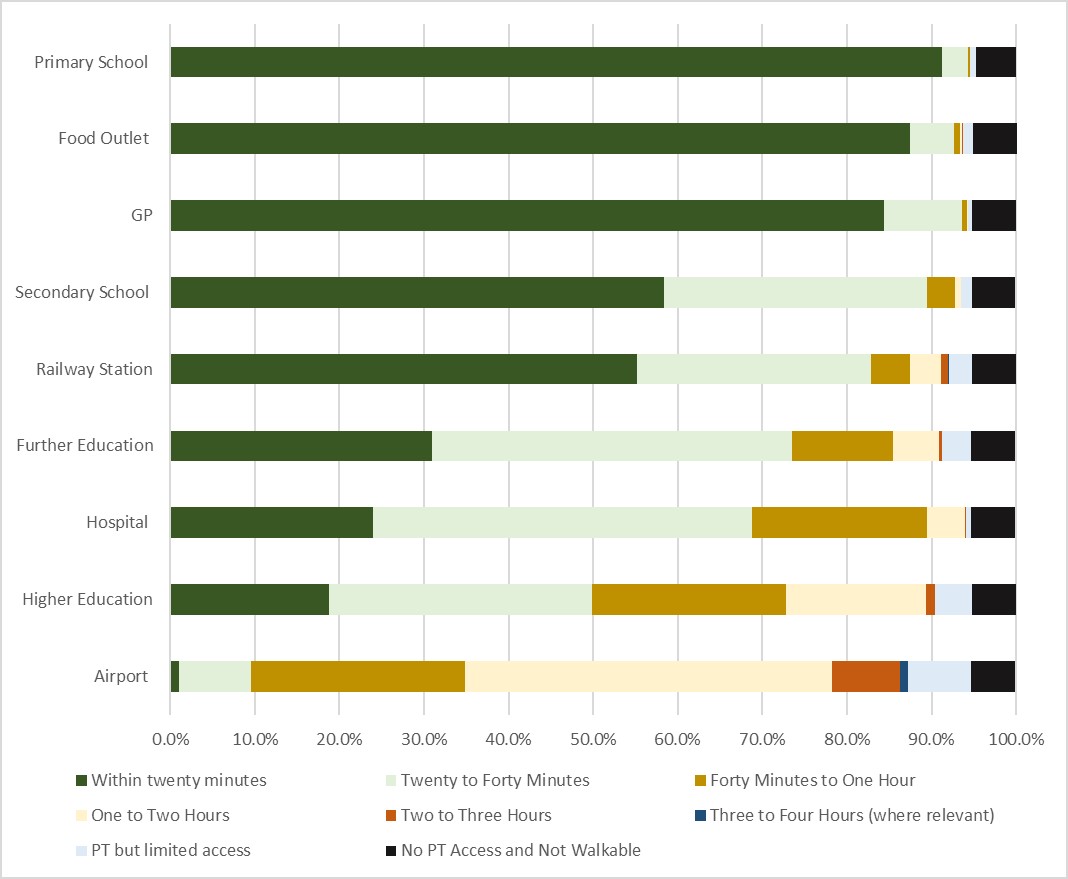

Overall

- Looking at key services, the most accessible are primary schools. These are accessible by public transport within 20 minutes by 91% of data zones (between 6:00am and 9:00am), followed by large food outlets, which 88% of data zones could access within 20 minutes (between 10:00am and 14:00pm).

- Airports were the least accessible, with 8% of data zones not being able to access these within four hours even when public transport links were available. This was followed by higher education facilities, with 4% of data zones being unable to access a facility within four hours even when public transport was available. By contrast, 19% of data zones could access higher education within 20 minutes.

- A graph of these results is provided in Figure 2. A copy of this table and a table of these results by local authority is provided in the accompanying dataset.

SIMD

- More deprived areas had slightly better access to public transport than less deprived areas. In the most deprived 20% of areas, only 0.2% of the data zones had no access to public transport, which was the lowest of all the quintiles. The most deprived 20% of data zones had the highest percentage that could access primary schools (99%), GPs (96%), food outlets (97%), secondary schools (71%), railway stations (71%) and further education (43%) within twenty minutes.

- A copy of the SIMD data is provided in the accompanying dataset. The data that was used on the SIMD ranking of datasets is available.

Rurality

- Urban areas, and large urban areas in particular, tended to have better access to services than rural areas. In around 24% of remote rural areas, there was no access to public transport, as was the case in around 18% of accessible rural areas (compared to around 1% of data zones in large urban areas).

- For instance, while 95% of the data zones in large urban areas could access a GP within 20 minutes via walking or public transport, this was only the case for 45% of remote rural areas (although it was the case for 91% of accessible rural areas). While 97% of data zones in large urban areas could access a hospital within an hour via walking or public transport, this was only the case for 51% of data zones in remote rural areas (within the time bands outlined above).

- A copy of the rurality data is provided in the accompanying dataset.

Data zones with limited access

In total, there were 365 data zones – 95% of the total – that could access a public transport hub within an 800 metre walk from the PWC of the data zone. Across all Scotland’s data zones:

- 6,606 (94.7%) could access a bus stop within 800m

- 34 (0.5%) could access a coach stop within 800m

- 681 (9.8%) could access rail within 800m

- 29 (0.5%) could access a ferry within 800m

- 89 (1.3%) could access a tram or subway within 800m

Of the 5% remaining data zones that could not access public transport within this period, the largest number of data zones that could not access a public transport hub in any local authority was in Aberdeenshire, at 60, while the lowest was in Glasgow City, at two.

Rural areas had more areas like this, with 140 in accessible rural areas (18% of the total) and 104 in remote rural areas (24% of the total), compared to 29 in large urban areas (1% of the total). Ranking by SIMD, areas in quintile 1 – the most deprived – had the fewest areas like this, at 0.2%, compared to a high of 10% in areas in the less deprived 60-80%.

Indicator 3B: Journey times to areas of employment and education for individuals

Data has been provided on the number of jobs in and journey times to key employment destinations via public transport from the PWC of each data zone in Scotland. This indicator also uses data specifically developed for this report. To provide an estimate of access to employment, jobs have been identified via the Business Register and Employment Survey (BRES) from 2018 and journey times have been calculated using pre-pandemic data on service timetables (from January 2020). Then, data zones which contain 50% of the total employment have been identified as the key employment destinations within each local authority.

Using this criteria, 417 core employment sites have been identified. To ensure the accuracy of the time estimates, the destination points have been moved to the industry reporting the highest number of jobs. So, for example, in the event that healthcare was the largest employer in a zone, the marker has been moved to a hospital or a health centre. The number of data zones within each local authority that comprise 50% of the jobs destinations varies. For example, the selected 50% of jobs in Dundee City are located across 8 data zones. However, in comparison, the selected 50% of jobs in Aberdeenshire are located across 32 data zones.

This approach was adopted for feasibility: given the wide range of employment locations across the country as a whole, manually incorporating all of them the model would be extremely labour intensive and could not be done at this time. It should be noted that, because the destinations represent 50% of the total jobs, the figures should be treated as indicative estimates of the availability of jobs, rather than exhaustively reflecting all available jobs.

Two separate datasets have been developed, one for the four hour period between 6:00am and 10:00am (the AM window) and one for between 10:00am and 2:00pm (the PM window). As above, the times below relate to Tuesday.

In this section, data on access to further and higher education is discussed in detail.

Overall

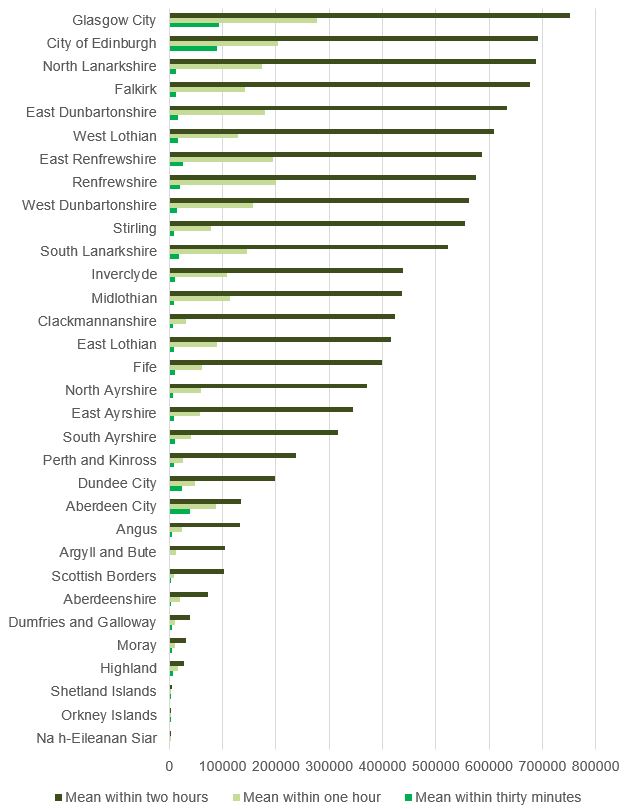

- Within the four hour AM slot, a mean of 27,387 jobs were available via employment sites across all data zones within half an hour via public transport. A mean of 115,797 jobs were available within one hour via public transport.

- Within the four hour PM slot, a mean of 22,834 jobs were available via employment sites in employment destinations across all data zones within half an hour via public transport. A mean of 108,750 jobs were available within one hour via public transport.

- Within the four hour AM slot, a mean of 427,704 jobs were available via employment sites across all data zones within two hours via public transport. Within the four hour PM slot, a mean of 426,145 jobs were available within two hours via public transport.

Local Authority

- Looking at the mean jobs available via employment sites within each data zone within the AM timeslot, grouped by local authority, Glasgow City has both the highest mean of jobs within thirty minutes (92,485) and within one hour (277,649). This was also the case in the PM slot, although the overall averages were slightly lower (79,658 and 264,586).

- By comparison, the islands tended to have the lowest mean numbers of jobs accessible via employment sites within the PM time frames. Six local authorities had an average lower than 3000: Aberdeenshire (2,970), Scottish Borders (2,762), Shetland Islands (2,658), Orkney Islands (2,396), Argyll and Bute (2,007) and Na h-Eileanan Siar (1,867). Looking at jobs available within an hour, the lowest number was Na h-Eileanan Siar, at 3,274. The distribution was the same in the PM slot, although the volumes varied slightly (slightly higher in some cases and slightly lower in other cases).

- A full breakdown of the average jobs in data zones, grouped by local authority in the AM slot can be seen in Figure 3. As this demonstrates, there are substantial differences between local authorities and there is substantial variation in the number of jobs available within the time bands. A full list is available in the accompanying dataset.

SIMD

- In terms of the mean jobs available via employment sites per data zone using public transport, the average number of jobs varied by SIMD quintile.

- For example, in the AM slot, in the most deprived quintile there were 36,617 jobs via employment sites within thirty minutes, 156,993 available within an hour and 547,509 jobs within two hours. By comparison, in the least deprived quintile, there were 33,073 jobs on average within thirty minutes, 125,182 jobs within an hour and 449,343 jobs within two hours.

- A full list is available in the accompanying dataset.

Rurality

- Data zones in urban areas, on average, had better access to jobs via employment sites using public transport than rural areas. Rurality here is calculated on the basis of the Scottish Government sixfold urban-rural classification. Areas are classified here into ‘large urban areas’, ‘other urban areas’, ‘accessible small towns’, ‘remote small towns’, ‘accessible rural areas’ and ‘remote rural areas’. Further information on the classification scheme and the data used for this analysis has been published by the Scottish Government.

- In the AM slot, in large urban areas via employment sites using public transport, there was an average of 65,569 jobs available within thirty minutes, 202,614 within one hour and 589,887 jobs available within two hours. By comparison, in remote rural areas, there was an average of 662 jobs available within thirty minutes, 3,272 within one hour and 28,383 within two hours. Accessible small towns had fewer jobs within these time slots when compared to accessible rural areas (2,023 compared to 4,396, 11,902 compared to 26,820 and 75,528 compared to 226,464). The pattern within the PM slot was comparable, although the absolute numbers were slightly lower.

- A full list is available in the accompanying dataset.

Data zones with No Access

In the four hour AM window between 6am and 10am, there were 424 data zones (6% of the total) that could not access any jobs via employment sites via public transport within four hours. By contrast, in the PM window, where 453 data zones (7% of the total) were in this position (an additional 29 data zones). There was also two data zones which could not access a public transport stop within 800 metres but could walk to an employment destination.

More specifically:

- There were 33 with access to public transport but that the model could not access any jobs via employment sites within either window using public transport

- There were 61 data zones with access to public transport that could not access any jobs via employment sites within the four hour AM window

- There were 90 data zones with access to public transport that could not access any jobs via employment sites within the four hour PM window

In addition, in terms of the contrasts between data-zone access:

- There were 28 with access to public transport where the individual data zone could not access any jobs via employment sites using public transport within the earlier window, but could access at least one in the later window.

- There were 57 where there opposite was true, i.e. there was access jobs via employment sites using public transport in the earlier window but not in the later window.

In cases where a data zone could access jobs in one window but not the other, this is likely to reflect public transport scheduling.

Access to Education: Further Education and Higher Education

This section discusses data from the previous section in more detail, specifically with regard to further education and higher education. Further education refers to post-secondary school education that is not undergraduate or postgraduate in nature. Higher education, by contrast, refers to undergraduate and postgraduate education. The timeslots for Further and Higher education were as follows:

- Further education – between 6:00am and 9:00am

- Higher education – between 6:00am and 9:00am

Further Education

Across all data zones, 31% could access further education via public transport within twenty minutes in these periods, which increased to 74% within forty minutes. For 6%, however, access took between one hour and three hours, while a further 4%, despite having transport links, could not get there within the allocated timeslot. By contrast, 65% of the data zones in Glasgow City had access within twenty minutes, the highest of any local authority.

SIMD

In the most deprived areas, 43% of the data zones could access further education within twenty minutes, increasing to 90% within forty minutes and 97% could do within one hour. By contrast, 2% took between one and two hours and 0.6% had access to public transport but had no access within the allocated three hour timeslot. This was higher than within the least deprived areas, where 28% could access it within twenty minutes, 74% within forty minutes and 87% within one hour.

Rurality

In large urban areas, 47% of the data zones could access further education by public transport within twenty minutes, and 95% could do so within forty minutes. In these areas, 98% could do within one hour, while only 0.5% had links but no access within the allocated time period. In accessible rural areas, 7% could access it within twenty minutes, 40% within forty minutes and 64% could access it within one hour. In remote rural areas, 22% could reach further education within an hour.

Higher Education

Across all data zones, 19% could access these sites within twenty minutes using public transport, which increased to 50% within forty minutes. For 18% of the data zones, however, access took between one hour and three hours, with a further 4%, despite having transport links, not having access to a Higher Education facility within the allocated timeslot. By contrast, 46% of the data zones in Dundee City could reach Higher Education within this twenty minutes, the highest of any local authority.

SIMD

- In the most deprived areas, 20% of the data zones could access higher education with twenty minutes, and 57% could do this within forty minutes. This increased to 81% within one hour, although for 17% of data zones it took between one and three hours. Around 2% had access to public transport but could not reach it within the allotted three hour timeslot.

- By contrast, 23% of the data zones in least deprived areas could access higher education in twenty minutes, with 56% able to do so in forty minutes and 79% able to do within an hour. For 12% it took between one and three hours. 3% had access to public transport but could not reach it within the allotted three hour timeslot.

Rurality

In large urban areas, 42% of the data zones could access higher education within twenty minutes, increasing to 92% within forty minutes. 98% could do within one hour, while only 0.5% had links but no access within the period. In accessible rural areas, 2% could access it within twenty minutes, 23% within forty minutes and 47% could do so within one hour. In remote rural areas, 18% could reach higher education within an hour.

Indicator 3C: Performance Measures of Public Transport Modes

- Urban areas tended be more satisfied than rural areas.

This section examines overall satisfaction with public transport by local authority. The data for this section comes from the Local Authority Tables of Transport and Travel in Scotland (TATIS), based on data from the Scottish Household Survey. Results comparing local authorities should be treated with caution given the small sample sizes recorded for individual local authority satisfaction scores.

Responses to specific questions are compared by rurality and by Regional Transport Partnership (RTP), given the relatively low sample sizes for the local authority tables in TATIS in relation to these questions. The section on specific satisfaction questions considers:

- whether services run to timetable,

- whether the service is stable and not regularly changing,

- whether the services are clean,

- whether buses are environmentally friendly (only for buses),

- whether it is simple deciding what type of ticket is needed,

- whether finding out about routes and times is easy,

- whether it is easy to change from buses to other forms of transport,

- whether bus fares are good value, and;

- whether people feel safe/secure on bus during the evening/during the day.

Overall Satisfaction

- Looking at variation within local authorities, the highest satisfaction with public transport can be found in the City of Edinburgh, at 88%. By comparison, the lowest satisfaction is found in South Ayrshire, at 44%. However, in South Ayrshire, dissatisfaction was also low, at 6% (the second lowest, after Edinburgh at 4%), with 51% neither satisfied nor dissatisfied. Dissatisfaction was highest in Aberdeenshire, at 35%, followed by Highland at 33%. Highland also had the second lowest satisfaction, after South Ayrshire, at 48%.

- Looking at satisfaction across rurality, this was highest in large urban areas, at 77%, and lowest in remote rural areas, at 48%. The highest dissatisfaction, was also in remote rural areas, 36%, while the lowest dissatisfaction was in large urban areas, at 11%.

- Looking at Regional Transport Partnerships (RTPs), the highest satisfaction with public transport was in the South East Scotland RTP, at 75%, and lowest in the Highlands and Islands RTP, at 53%. In terms of dissatisfaction, this was lowest in the South East Scotland RTP, at 10%, and the joint highest in the Highlands and Islands RTP and North East RTP, at 29% in both.

Buses

In terms of responses to specific questions, this section highlights the statistically significant differences between urban and rural classification.

- ‘Buses are environmentally friendly’: 57% of those in urban areas agreed with this, compared to 47% of those in rural areas.

- ‘I feel personally safe and secure on the bus during the evening’: 68% of those in urban areas agreed with this, compared to 74% of those in rural areas.

- ‘It’s easy changing to other forms of transport’: 71% of those in urban areas agreed with this, compared to 65% of those in rural areas.

- Further breakdowns are available in the accompanying dataset.

Trains

In terms of responses to specific questions, this section highlights the statistically significant differences between urban and rural classification.

- ‘Fares are good value’: 49% of those in urban areas agreed with this, compared to 42% of those in rural areas.

- Further breakdowns are available in the accompanying dataset.

Indicator 3D: Barriers to Public Transport Use and Access

Given the emphasis on geography, the barriers considered here are those which relate most directly to geography, i.e. inconvenient, no direct route, lack of service, too infrequent and long walk to bus stop (for buses) and no nearby station, inconvenient and no direct route (for trains). This section highlights the statistically significant differences between urban and rural classification. Further breakdowns are available in the accompanying dataset.

It should be noted that, when choosing barriers, many respondents only chose one key barrier (although they had the option to choose more than one). For example, a respondent who experienced ‘lack of service’ as well as ‘no nearby station’, may have chosen the former to the exclusion of the latter. The statistics below should be interpreted in this context.

Buses

- ‘Lack of service’: 4% of those in urban areas reported this as a barrier, compared to 22% of those in rural areas.

- ‘No direct route’: 6% of those in urban areas reported this as a barrier, compared to 10% of those in rural areas.

Trains

- ‘No nearby station’: among those who hadn’t used the train the last month, this was reported by 20% of those in urban areas, compared to 41% of those in rural areas. Among those that had used the train in the last month, the numbers were 11% and 22% respectively

- ‘Lack of service’: among those who hadn’t used the train in the last month, this was reported by 1% of those in urban areas, compared to 3% of those in rural areas.

- ‘No direct route’: among those who hadn’t used the train in the last month, this was reported by 3% of those in urban areas, compared to 5% of those in rural areas.

Indicator 3E: Tourism/Visitor Numbers

- Edinburgh and the Lothians, Glasgow and Highlands are the most prominent tourist destinations in Scotland.

The data in this section comes from two primary sources. These include the national and regional statistics available from Visit Scotland and data from the Office of National Statistics. The tourism figures from Visit Scotland combine averaged figures for 2017-19 for some locations, while for others provide figures for 2019.

This was done to reflect the fact that, for some locations, this was done to reduce error margins for regions where sample sizes were relatively small.

The areas for which 2017-19 average figures were used included Argyll and the Isles, Ayrshire and Arran, Dumfries & Galloway, Dundee & Argus, Fife, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs, Stirling & Forth Valley and the Scottish Borders. For ease, 2019 will be used in the discussion below in both cases.

Several tourist destinations – namely Shetland, Orkney and the Scottish National Parks - did not have comparable statistics and so are not included here in the following area comparisons.

Overall Visits and Spending

- Data from the ONS indicates that overseas visits to Scotland increased from 2.6 million in 2009 to 3.5 million in 2019.

- Overall, in 2019, including trips from the UK and Scotland, Visit Scotland estimates that there were 151 million trips to Scotland. There were also 75 million nights spent in Scotland by tourists (including those visiting from other parts of Scotland) and a total of £11.6 billion spent. These figures include both day visits and overnight trips.

Overnight Visits and Stays

- In terms of overnight visits, in 2019 there were a total of 17.5 million overnight visits to Scotland. Of these, 5.3 million were to Edinburgh and the Lothians, 3.1 million were to Glasgow and 2.9 million were to the Highlands. These destinations represent almost two-thirds of the total (64%).

- Looking again at overnight stays, Edinburgh and the Lothians had the most international visitors, at 2.3 million for a total of 12.8 million nights. Edinburgh also had the most visits from the rest of the UK at 1.9 million, for 5.3 million nights. By contrast, the Highlands had the most visitors from Scotland at 1.5 million over 4.9 million nights.

- Looking at spending on overnight visits in 2019, the Highlands attracted the most spending from Scottish visitors, at £291 million. In terms of spending from visitors from the UK and the rest of the world, both were highest in Edinburgh and the Lothians, at £499 million and £1.2 billion, respectively.

Day Trips

In terms of day trips, Glasgow received the most, with 29.7 million trips in 2019. In terms of spending, however, the highest spending from day trips was in Edinburgh and the Lothians, at £1.31 billion, closely followed by Glasgow at £1.25 billion.

< Previous | Contents | Next >